When it reached the Massachusetts Supreme Court, the case of Franklin v Albert [1] asked a specific question: how long after an alleged medical error can the person who claims injury file and pursue a malpractice suit? The question and the Massachusetts court's answer have gained importance in an era of widespread screening for asymptomatic disease. If a patient suffers harm as the result of an error in prescribing or a mistake during surgery, that harm is known to the patient or others soon afterward, certainly well before the time limit expires for filing personal injury claims in most jurisdictions. But if a mammogram, say, or a lung CT is misread as negative for cancer, that person has no way of knowing about the mistake, perhaps not until he or she develops symptoms. If the individual who was tested develops the disease years later—as happened to Peter Franklin—can he or she still sue the radiologist who misread the image? Within how many years after the x-ray or other scan took place must the claim be brought? That is the question that Franklin v Albert asked the court.

Peter Franklin's Case

Peter Franklin was a second-year medical student when he checked into Massachusetts General Hospital in January 1974 to have his wisdom teeth extracted under general anesthesia. He was experiencing some chest pain at the time, so a chest x-ray was ordered. Franklin underwent the oral surgery and was discharged 2 days after his admission by Thomas Albert, a resident, who noted on the discharge summary that Franklin's presurgery chest x-ray had been normal.

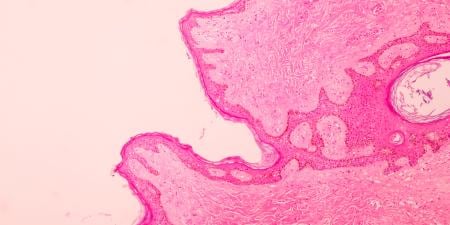

In January 1978, Franklin returned to Mass General for a chest x-ray, this time because he had flu-like symptoms. On this occasion, the x-ray showed "an enormous tumor filling Peter's chest, compressing his lungs from the middle and pushing outward" [2]. Franklin was diagnosed with Hodgkins disease. Surprised that the disease had progressed to such an advanced stage without detection, Franklin's father, a physician who was also on staff at Mass General, had 1 of the radiologists pull his son's 1974 x-ray. Not only did this radiologist find evidence of a mass in the earlier film, he found that the radiologist who had read it in 1974 had also noted "an apparent left superior mediastinal widening" and had recommended further evaluation of the abnormality [3].

Peter Franklin's disease, which might have been cured by radiation had it been diagnosed 4 years earlier, required months of chemotherapy and high doses of radiation. A new chemotherapy regimen was employed to combat the resistant malignancy and so weakened Franklin's immune system that he suffered a severe viral infection of the lungs, forcing him to take a leave of absence from medical school [4]. Franklin brought suit against Dr. Albert and Mass General 6 months after discovering the 1974 radiology report. The attorneys for defendants Albert and Massachusetts General Hospital asked the court for summary judgment—that is, a decision in their favor that precluded the need for trial—because, under Massachusetts General Law, suits for medical harm had to be brought within 3 years of the injury. Inasmuch as 4 years and 6 months had elapsed between the 1974 x-ray and the 1978 suit, the trial court granted Albert and the hospital the summary judgment they requested.

When Does the Cause-of-Action "Accrue"?

In the words of chapter 206, section 4 of Massachusetts General Law, as amended in 1965, "actions of…tort for malpractice, error or mistake against physicians, surgeons, ...hospitals…shall be commenced only within 3 years next after the cause of action accrues" [5]. The trial court that first heard the Franklin case had relied upon that section of the General Law and also upon a precedent case, Pasquale v Chandler [6], to determine at what point that cause-of-action clock began to tick away the 3 years. The Pasqualecourt had ruled in 1966 that the cause of action "accrues" at the time the malpractice takes place and "not when the actual damage results or is ascertained" [7]. In Franklin's case that meant that the statute of limitations clock had begun ticking when the January 1974 x-ray was taken and had expired 3 years later in January 1977, 1 year before Peter's symptoms led to the second x-ray and the Hodgkins diagnosis.

Looking at these facts, the Massachusetts Supreme Court recognized that the Pasquale decision could deprive injured parties of access to remedy before they were even aware that they had been harmed. Such a ruling was unjust in the view of that court, which decided instead that "a cause of action for medical malpractice accrues when the plaintiff learns, or reasonably should have learned, that he has been harmed by the defendant's conduct" [8]. There was no "reasonable" way that Peter Franklin could have learned, upon leaving the hospital after oral surgery in 1974, that he had been harmed by Dr. Albert's inaccurate discharge summary of the chest x-ray.

Implications of Franklin v Albert in an Era of Widespread Screening

The 1980 decision of the Massachusetts Supreme Court that the cause of action in medical malpractice "accrues" when the plaintiff learns of the harm still stands and is in line with the discovery rules in the vast majority of states. As asymptomatic screening becomes more popular in our increasingly health- and mortality-conscious society, the ruling has a message for patients and physicians. The decision warns, or should warn, patients and other members of the public to be certain that all screens and tests they undergo for medical conditions will be interpreted by physicians. Physicians are accountable for their interpretations of screening and diagnostic tests, the Massachusetts decision tells us, long after those interpretations are recorded. Should an error occur, as in the case of Peter Franklin, the patient can recover economic harms. When physicians do not order screening or interpret the results—as may occur in some commerical screening contexts—patients may find it more difficult to obtain timely recourse for harmful oversights.

It is in patients' best interest to take the results of unordered, commercial screens to their own physicians immediately. While Franklin v Albert says patients have 3 years from the time they discover a harm until they can file a claim, certainly no prudent person would allow so much time to elapse before having screening results interpreted and receiving proper recommendations and, if necessary, treatment.

For physicians, Franklin v Albert underscores once again the critical importance of communication and follow-up among all members of a patient's care team. One must wonder how it came about that neither Peter Franklin's oral surgeon nor his anesthesiologist discussed his x-ray findings and recommendations with him.

Because of the increased marketing of screening exams to the public, there are some indirect implications of Franklin v Albert for physicians. More patients are requesting screening exams in the absence of symptoms and bringing reports from tests and scans done in nonclinical settings to their physicians, asking what the reports mean. In response to this trend, the American Medical Association recently developed policy on the responsibilities of physicians who perform tests they do not deem medically necessary at the request of the patients. This policy, Opinion 8.045 Direct-to-Consumer Diagnostic Imaging Tests, states that "once a physician agrees to perform the test, a patient-physician relationship is established, with all the obligations such a relationship entails" [9]. Further, "in the absence of a referring physician who orders the test, the testing physician assumes responsibility for relevant clinical evaluation, as well as pre-test and post-test counseling" [9]. Hence, physicians who test, or interpret tests for, patients in the absence of medical indication assume the responsibility for harms that accrue to the patient as a result of misinterpretation of results or failure to recommend appropriate follow-up.

Follow-up tests can themselves expose patients to risk and discomfort, sometimes unnecessarily. Physicians must discuss the risks of invasive follow-up tests with patients and be willing to help them decide whether those risks are warranted and acceptable. And, of course, the screen results, the discussions, and the patient's decision must be documented.

References

-

Franklin v Albert, 381 Mass 611; 411 NE2d; Mass (1980).

-

Gawande A. The malpractice mess: who pays the price when patients sue doctors? The New Yorker. November 14, 2005: 67.

-

Franklin v Albert, 381 Mass 613.

-

Gawande, 69.

-

Massachusetts General Laws c.260, sec. 4. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/legis/laws/mgl/260-4.htm. Accessed December 28, 2005.

-

Pasquale v Chandler, 350 Mass 450; 215 NE2d 319; Mass (1966).

-

Pasquale v Chandler, 456.

-

Franklin v Albert, 381 Mass 612.

-

Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association. Opinion 8.045 Direct-to-conusmer diagnostic imaging tests. This opinion is based on CEJA Report 3-A-05, which was approved by the AMA House of Delegates at its June 2005 Annual Meeting. The opinion will appear in the next version of PolicyFinder, available on line at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/noindex/category/11760.html, and in the next print edition of the AMA Code of Medical Ethics.