Expectant parents dream of giving birth to a beautiful, robust and "perfect" baby. In reality this does not always happen. When things go wrong there is sometimes nothing parents can do to ameliorate the condition of their afflicted child. For others, the imperfections are so slight that they barely affect the child's leading a normal life. It is a specific group caught in the middle of this spectrum—high-functioning children with Down syndrome (DS)—who evoke the ethical question discussed here. That is, is it ethical for parents to subject children with DS to purely cosmetic surgery that offers no medical benefit for them before the children are old enough to give any informed and freely considered assent?

As the mother of a "perfect" child, I can only imagine that it is a crushing frustration for parents of high-achieving boys and girls with Down syndrome to see how tantalizingly close their offspring come to functioning as their peers do. It is understandable that some of these parents, fearing their children will be waylaid at the start by their distinctive features, might choose purely cosmetic surgery at an early age in an attempt to make them more visually acceptable. These parents focus on the importance of first impressions—if their children look like the other kids, they argue, they will have a better chance of being accepted after the behavioral and emotional differences of Down syndrome become apparent.

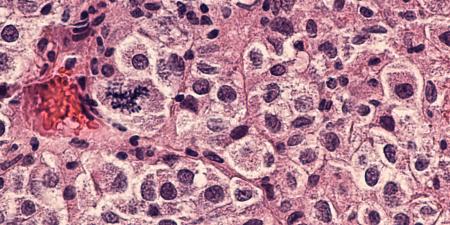

I cannot fault parents for wanting to protect their children from the stigma of not meeting subjective standards held by ignorant people regarding "acceptable" appearance. Though we may not agree with them, it is not hard to understand why these parents seek to erase what they believe to be triggers of prejudice by "fixing" their children's faces as soon as possible. Nevertheless, pursuing this course raises both practical and ethical questions. Practically, we must ask if the surgery, which carries physical risks without medical benefits, provides the intended good effect. Ethically, we must consider whether the benefits outweigh the burdens. The surgeries in question are performed under general anesthesia and often include resection of the tongue, lifting of the bridge of the nose, removal of fat from the neck, placement of implants in the cheekbones and removal of the distinctive folds of the eyelids.

From a practical perspective, there is studied reason to question whether well-intentioned deception-by-surgery actually does erase the vulnerability of the child with Down syndrome. Most people recognize the facial characteristics of DS and are immediately signaled that the child will be more vulnerable, a bit slower and sweeter, a bit needier. While the child's features may alert bullies that they have found a target, kind people are alerted instead to be more understanding. Those distinctive features thus seem to invite loving care as much as they do discrimination [1]. Further, we must inquire—again in the face of a small child's subjection to medically unwarranted surgery—whether bullies and other intolerant persons will be any kinder if their recognition of the child as a target is merely postponed. This is a particularly telling question in light of research that shows little correlation between DS features and discrimination [2]. Still, if for the sake of argument we suggest that people who treat these children badly are indeed triggered by their facial features, we must consider findings that, while parents report being pleased with the results of surgery [3], independent reviewers discern "no improvement" in the appearance of children with DS who have undergone cosmetic surgery" [4].

Toward a more Tolerant Society

Ethically, I am most concerned that cosmetic surgery moves the onus from the "normal" person's moral obligation to be tolerant to the small shoulders of children with DS, requiring them to endure the fear and pain of surgery in hopes of stemming the intolerance of others. The position of the National Down Syndrome Society in the United States is that the focus should be on inclusion and acceptance of the children as they are and not on subjecting them to surgical intervention simply to make them more pleasing to others [5]. The slogan of Down Syndrome South Africa is "Count Us In," and that organization suggests that surgically altering the facial features of the child with DS runs counter to prevailing efforts to nurture societal acceptance for these children just as they are [6]. Finally, in light of today's move toward involving young children in their health care decision making, I point out the serious ethical error of subjecting any child to a purely cosmetic procedure with no medical benefit before he or she can offer or withhold assent, much less consent. If it is expected that the child with DS will, with age, be able to decide for him or herself whether the benefits of surgery would outweigh the burdens, the parents should seriously consider waiting until that time. If, on the other hand, the child is not sufficiently high achieving for one to reasonably believe that that day will ever come, then the ethical strictures against cosmetic surgery to "normalize" the child intensify.

In light of objective evidence that purely cosmetic surgery does not accomplish any real benefit for children with DS, I believe that the only ethical course is to wait until a particular child achieves decision-making maturity sufficient for the task. Given that surgery does nothing to address the syndrome per se, it is impossible for me to justify ethically the risks and suffering visited on the child when the decision is made by others. He or she will remain a person with Down syndrome, with or without the surgery, still subject to the discrimination of the ignorant and intolerant. It is those persons who should accommodate the child with Down syndrome, not vice versa.

References

-

Lewis M. Hearing Parental Voices: An Opinion Survey on the Use of Plastic Surgery for Children With Down Syndrome. Brandeis University. Available at: http://www.bio.brandeis.edu/downsyndrome/. Accessed June 27, 2006.

-

For example, Pueschel SM, Monteiro LA, Erickson M. Parents' and physicians' perceptions of facial plastic surgery in children with Down's Syndrome. J Ment Defic Res. 1986;30(Pt 1):71-79.

-

For example, Lemperle G, Radu D. Facial plastic surgery in children with Down's syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66(33):337-345; Jones RB. Parental consent to cosmetic facial surgery in Down's syndrome. J Med Ethics. 2000;26:101-102.

-

For example, Arndt EM, Lefebvre A, Travis F, Munro IR. Fact and fantasy: psychological consequences of facial surgery in 24 Down syndrome children. Br J Plastic Surg. 1986;39(4):498-504.

-

National Down Syndrome Society. NDSS Position Statement on Cosmetic Surgery for Children with Down Syndrome. Available at: http://www.ndss.org/content.cfm?fuseaction=NwsEvt.PressPSArticle&article=698. Accessed June 23, 2006.

-

Down Syndrome South Africa. Cosmetic Surgery. Available at: http://www.downsyndrome.org.za/main.aspx?artid=44. Accessed June 23, 2006.