Case

Jane Patterson was brought to the emergency department after an automobile accident in which she sustained serious but not life-threatening injuries. After being stabilized, she was wheeled to the orthopedic floor for surgery to repair her broken femur. Jane, who was 33 and unmarried, called her parents from the hospital. When they arrived several hours later they were relieved to find that she was doing well. Surgery was performed the next afternoon, and the repair was successful. But events soon took a turn for the worse.

While her parents were out eating lunch, Ms. Patterson was found to be unresponsive by her nurse. A quick assessment revealed that she was in cardiac arrest. A code was called, and CPR was initiated. After multiple defibrillator shocks and injections over a 30 minute period, a regular heart rhythm was finally restored, but Ms. Patterson remained unconscious and no one was sure how long her brain had been oxygen-deprived. After the team was confident that Ms. Patterson was stabilized, she was intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

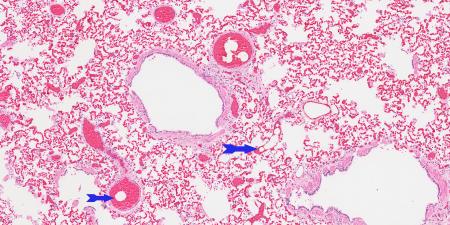

Upon returning from lunch, the Pattersons were shocked to find Jane unconscious and on a ventilator. The medical team suspected that a fat embolus had caused her acute decompensation. The ICU team recognized the gravity of the situation, but given Ms. Patterson’s age they decided to pursue aggressive measures to restore her to good health. Over the next week she appeared to improve; her blood pressure stabilized and she began making spontaneous movements. Each day the ICU team reported Ms. Patterson’s progress to the family, discussing the daily lab values and their daughter’s overall physical functioning. The Pattersons clung to these updates and believed that their daughter was getting better. The ICU team knew that, despite the change in some physical functions, Ms. Patterson remained neurologically impaired, with little hope for a meaningful recovery. Her parents also knew that she had not regained consciousness and waited expectantly for her to come out of her coma.

The medical team was unable to wean Ms. Patterson from the ventilator, and the time had come to decide on a tracheotomy for permanent ventilator support. The next day, the ICU attending physician scheduled a conference with the Pattersons to discuss Jane’s prognosis and raise the possibility of forgoing this traumatic procedure and letting an infection that Jane had recently developed take its course. The Pattersons were visibly upset at the mention of their daughter’s brain injury and seemed unprepared to discuss the likelihood that she would never regain consciousness. The attending physician was puzzled by the family’s reaction because she believed that this outcome had been clear all along. Angry and emotionally distraught, Mr. Patterson said, “Each day you tell us she’s getting better. Her blood pressure is stable, and the blood tests look good, and pneumonia is treatable. Why would we want to stop now? We don’t want our daughter to die.”

This reaction greatly frustrated the ICU team, who believed the family “just didn’t get it.” Jane would never recover, and they were no longer comfortable with providing painful and expensive treatment to someone they considered to be in a vegetative state. The team tried to explain this and attempted to reason with the family, but the message never seemed to get through. Each day the team became more exasperated, until eventually its members actively avoided Jane’s parents and hurried by her room. When it came time to discuss moving Jane to a long-term care facility, the ICU team felt unable to communicate with the Pattersons. At this point, the palliative care team was called to intervene.

Commentary

What Happened Here?

A previously healthy young person sustains injuries in a motor vehicle accident, none of which is life-threatening. After a surgical fracture repair, a presumed fat embolism leads to cardiac arrest and anoxic brain injury. What should have been an uneventful recovery and return to a normal life suddenly becomes an inconceivable tragedy. Both the physicians and the patient’s parents struggle at first to deny the irrevocability of this event, focusing instead on signs of stabilization in blood pressure or laboratory findings—choosing to “observe her and see how she does.” The parents, picking up on the can-do atmosphere of the ICU with its attention to the physiologic details of critical illness, gladly narrow their focus in concert with the care team. The physicians soon realize, however, the low likelihood of meaningful neurological recovery, but the awkwardness of shifting from the hopeful stance of the first few days, combined with the sense of professional failure about this terrible outcome, inhibit their communication of the gravity of the prognosis to the distraught parents.

As more days pass, the physicians assume that the hopelessness of the situation is obvious to the parents. The parents, meanwhile, are still hoping. They have taken their cues from improving lab tests and limb movement, a stance established by the watchful waiting approach of the first few days, and do not draw the same conclusion as the medical team. Their daughter is in the ICU on all kinds of life support—surely modern medicine can fix this. The physician’s belated attempt to bring the unfortunate reality to the parents’ awareness is met with disbelief and cognitive dissonance. “You told us to wait and see how much function she would recover. Are you giving up on her after only a week? If you thought she wasn’t going to get better, why do have her in the ICU on all these machines?” Forgetting that the patient’s parents don’t share their knowledge of the usual outcome of such an injury, the physicians are surprised by this refusal to accept what is obvious to them. The parents no longer trust the physicians to put the best interest of their daughter first and instead go into an oppositional and advocacy mode—“We have to protect our daughter from these doctors—they’ve already given up on her.”

Why Does this Happen?

A number of factors contribute to this scenario—frustrating but common during critical illness. These include the knowledge gap between family members and physicians; unconscious reactions and feelings of family and doctors toward each other, also known as transference and countertransference [1]; physician discomfort with and avoidance of patients with bad prognoses and outcomes; and lack of physician education in the skills necessary to care for patients when medicine can’t save them.

- Knowledge gap. After a lengthy period of cardiac arrest with no oxygen to the brain, a young woman fails to wake up from her coma. Interestingly, both parties (doctors and family) hold fast to hope for recovery early in this patient’s course. She is young and previously healthy. But after a week with no improvement, the doctors shift their expectations based on the data—the odds of neurological recovery sufficient to allow return to an independent existence are close to zero. Meanwhile, deluged with stories of miracle recoveries after comas from friends and family members, the parents are gathering their strength for a long but hopeful vigil. They have no way of knowing “the numbers,” nor have they witnessed such a situation before. If their online searches suggest that the risks of permanent coma are high, they figure this outcome does not apply to them, given Jane's recent progress. The kidney specialist says their daughter’s kidneys are back to normal; the infectious disease doctor says there is no sign of infection; the ICU doctors are suggesting a tracheotomy as a step toward weaning her off the ventilator. The family experiences these comments as evidence of desperately sought hope.

Though obvious to the health professionals, the neurological facts have not been consistently conveyed by the different specialists and are neither self-evident nor tolerable to contemplate from the family’s standpoint. These unstated and opposed perspectives are a major source of misunderstanding, mistrust and compounded suffering for all concerned. No matter how well-educated or seemingly “with-it” a family member may be, shock, denial and the need to hold on to hope inevitably cloud judgment and prevent a truly rational understanding of the big picture.

- Transference and countertransference. It is hard for physicians to internalize and understand the hope and power invested in them by desperately ill patients and their families [1]. Even among sophisticated, well-educated people, confrontation with mortality and suffering normally leads to an almost childlike faith in the physician-healer as the holder of the secret knowledge that will bring about the hoped-for miracle. This unconscious assignment of powers and abilities to the physician is called transference in the psychiatric literature. Although psychiatrists are trained to recognize and respond appropriately to the unconscious thoughts and desires of their patients, physicians of all specialties need these skills in order to both understand and respond professionally to the behaviors and the suffering of patients and their families.

Physicians experience an equivalent unconscious reaction to the patient or family, called countertransference. Countertransference is normal and inevitable, but recognizing and understanding it requires a conscious attempt on the part of physicians who wish to provide appropriate professional care to patients and families. In this case, the physicians’ anger at the parents for their (understandable and normal) stubborn hope for recovery is a good example of countertransference. Physicians unconsciously want to be forgiven for the patient’s bad outcome; they personalize and cannot bear the parent’s disappointment and rage, normal and understandable as those actions are. And not least, the confrontation with the senseless and random loss of life in a person of their own age is frequently painful. As a result of these physicians’ failure to monitor and control behaviors stemming from their own unconscious feelings, the suffering of this family is enormously compounded by what they experience as a devastating breach of faith with their previously trusted physicians.

- Physician discomfort with bad outcomes. Modern medical care is characterized by a typically American can-do attitude that asserts “with enough research, all disease and death can be defeated.” This culture of cure infuses medical education both in the classroom and on the floors of the hospital and clinics [2]. Learners are humiliated for missing a diagnosis and are expected to prevent and cure disease in all their patients. The inconvenient truth is that every patient will sicken and die, and it is beyond our power, even though we are physicians, to prevent it. Yet acceptance of mortality—how to learn to live with it and provide supportive presence and guidance to the patients and families going through it—is seldom named as an important physician competency and remains a rare skill among the attending physicians responsible for mentoring our students and residents [2]. Medical education must begin to convey the fact that all humans die and that, as a consequence, an essential competency of all physicians who care directly for patients is expert care of the dying and their families.

- Lack of education in how to approach the care of the seriously ill and their families. The skills required to engage in conversation about bad and sad medical outcomes are teachable and effective at improving patient-family understanding and satisfaction with care [3, 4]. These skills include the ability to open a dialogue, to listen, to reflect on what has been said and relay it back to the participants, to convey information in comprehensible bits, and to establish an ongoing relationship and treatment plan that demonstrates nonabandonment and commitment to the patient and family. Examples of the kinds of words that create trust and connection [5] include: “I am so sorry about what has happened to your daughter and I wish things were different.” “Have you or others in your family ever been through a situation similar to this one?” “What have the other doctors told you about what to expect at this point?” “What is your understanding of your daughter’s condition and what the future holds? What are you hoping we can accomplish for your daughter?”

After explaining the likely outcomes, pausing for clarification and questions and allowing the expression of feeling, it is time to lay out the options. The basis for establishing the alternatives to cure begins with an understanding of who the patient was before she was sick, her values and goals in life, and any opinions she might have expressed about her own life or that of highly publicized cases like that of Terri Schiavo.

In our case, the family now faces three choices. The first is to discontinue artificial life support and allow their daughter to die of the brain injury she has sustained. The second is to continue full life support including tracheotomy and feeding tube placement for a pre-specified period. This so-called time-limited trial of therapy allows for the small possibility of recovery and gives the family needed time to come to terms with what has happened. Option three is to accept for their daughter a life in an institution permanently dependent on medical technology without return to consciousness. Any one of these choices may be the best one for this patient and her family. It is the physician’s job to present the options and their pros and cons and to help the family relate these choices to what is known about the patient and her values and wishes or, if these are not known, her parents’ assessment of what is in her best interest. It is the parents who will live with themselves and the memory of their decision for the rest of their lives. Enhancing their ability to heal from this loss and to feel proud of the care they chose should be a high priority for physicians in a situation like this one. Our personal opinion of what the best decision might be for ourselves or our own family is not relevant to this family’s decision and must consciously be kept separate from the advice and counsel we give the family.

Managing Expectations

The antipathy that developed between the family and the doctors in this case was painful for all concerned and might have been prevented by avoiding false hope, assuring consistent communication from specified communicators, early focus on the patient as a person and her probable preferences, involving other team members for support, offering time-limited trials of treatment with clear endpoints and presenting realistic alternatives for a decision.

Avoid false hope. When the patient’s prognosis is poor, it is important to avoid instilling false hope. This can be conveyed by saying, for example, “She has suffered a devastating injury to her brain and we do not expect her to recover fully. We’ll watch her carefully over the next few days and speak with you daily here in the ICU about what the options are for her if she remains in a coma.” Hedging, focusing on irrelevant positives such as the blood pressure or renal function and providing encouragement about the possibility of outcomes that cannot realistically be expected only confuse and distract the family from the work of acceptance that they must begin.

Control communications. Minimize communication to the family from different subspecialists and arrange for a selected physician and nurse to consistently provide updates and support to the family. These individuals should spend more time listening to the family and their concerns than talking. Talking aloud helps people understand and modify their own thinking and brings the situation closer to reality.

Focus on what the patient would want. Begin early to ask about the kind of person the patient used to be—her values and beliefs and whether she said anything about what she might want if she were ever in a situation like this. This shifts some of the decision burden from the shoulders of the parents and toward an effort to honor their daughter’s spirit and beliefs.

Mobilize support. Engage other forms of support for the family—a social worker, chaplain and other family members or friends. This signals a shift in focus of care to the grieving family and helps convey the gravity of the situation to them.

Establish time-limited trials of therapy. Set time frames by saying, for instance, “If she does not show clear signs of neurological recovery by Friday, the odds are poor for a return to an independent life outside an institution. We will wait until Friday to discuss her future options, but in the meantime let’s think about what your daughter would want if she could tell us.” Time-limited trials give families space to come to terms with what has happened rather than rushing them into irrevocable decisions.

Clarify the choices. Offer realistic alternatives without judging the patient or family’s values. When deciding among alternatives—stopping life support, continued time-limited trial for a pre-specified period or institutionalization with long-term ventilator and nutritional support—there is no right answer, only the solution that is most consistent with who the patient was before the accident and what her parents can live with. Our presence and our expression of sorrow about what has befallen this family can be a powerful form of healing and comfort. Francis Peabody said it best—“The secret of the care of the patient is caring for the patient”—or, in this case, the patient’s family.

References

- Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS. The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA. 2001;286(23):3007-3014.

- Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403-407.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Saul J, Duffy A, Eves R. Efficacy of a Cancer Research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9307):650-656.

- Back AL, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA. Teaching communication skills to medical oncology fellows. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2433-2436.

- Quill TE, Arnold RM, Platt F. “I wish things were different”: expressing wishes in response to loss, futility, and unrealistic hopes. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(7):551-555.