We speak of Heaven who have not yet accomplished

Even this, the holiness of things

Precisely as they are, and never will!

—Franz Wright, Prescience. [1]

Where is the father?

Where is the father?

Where is the father?

Where is the father?

—Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows [2]

“Les Quatre Cents Coups”—“The 400 Blows”—was made by Francois Truffaut in 1959. It was his first film, and the first of four films which he would write, direct, produce and sometimes star in, devoted to the inner life of the child. The inspiration for the script was the story of Emperor Frederic II, who instructed that his children be raised without affection, permitted contact with only their nurses, not treated with brutality but never spoken to or touched [3]. These children all died very young. Truffaut said in an interview:

It is of this experiment by Emperor Frederic that we were thinking in writing the scenario of The Four Hundred Blows. We tried to imagine what would be the behavior of a child who survived such a treatment, on the brink of his thirteenth year. On the verge of revolt [3].

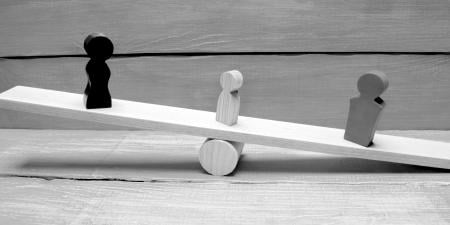

The deprivation of both language and physical comfort was for Truffaut the nadir of human experience. How could these “subtractions” be more poignant than in childhood, where the power and magic of words are first discovered? When the need to be held is greatest? Truffaut, a leading light of the French New Wave film movement, would not have said that he set out to make a film about ethics or healing. But this is a film for everyone who works with children and their parents, including, maybe even especially, physicians, given the deprivations, both necessary and chosen, of the environments in which we work. It’s difficult to watch “The 400 Blows” without feeling that this child could be any child in one of our hospital rooms or clinics anywhere in the world. Its value to our profession is that through Truffaut’s eyes, we are asked to see, hear and hope for a child along with his parents, without his parents, despite his parents but also, in part, as his parents.

To See

“The 400 Blows” opens with a pin-up of a nude female circulating among a group of prepubescent boys sitting at their classroom desks. The overbearing and often cruel instructor finds it in the hands of Antoine Doinel, the central figure of the film (and several others by Truffaut). So begins the growing antagonism between Antoine and the adults around him. Unable to concentrate on his studies, Antoine continually plays hooky, while at home there are often indiscreet fights about whether to send Antoine off to boarding school. In an attempt to salvage his academic career, Antoine devours the works of Honoré de Balzac. He creates an altar to the novelist and lights a votive candle beneath it for inspiration. But the shrine goes up in flames and Antoine is expelled for plagiarizing from Balzac’s “Search for the Absolute.” Finding his son uncontrollable, Antoine’s father turns him in to the authorities and relinquishes his custody to the state. When Antoine is taken to a correctional facility, his mother joins him on family day to make this announcement: “…don’t go crying to your father. He told me to tell you he doesn’t care about you anymore. So you will be sent to a labor center.”

As physicians and health professionals, we see the letting go and abandonment of ill children by their parents every day. The abandonment may be more subtle, it may have happened years before we see the child; it may not be conscious or deliberate, but for every parent who clings tightly to hope, there is another who has reached the end of his or her stamina or competence or capacity to care. Our facilities are often the labor centers to which these children have been sent.

Four years after making “The 400 Blows,” Truffaut called it his first Hitchcockian film because “one identifies with the child (Antoine Doinel) from the first shot to the last” [4]. In the final seconds of the film as Antoine escapes from the reformatory and runs to edge of the sea, he turns back and faces us; Truffaut freezes the frame, so the final image is of Antoine looking back at us almost as sculpture. In a film filled with the inevitable march of images and erasure, the permanence and finality of this image is especially significant, his haunted gaze back at the audience, the only ones to see him and therefore his true guardians.

We have all seen this look in a child who is brought into our care. The look that asks for affirmation, for understanding; it is a deeply personal look that, like Antoine's, can shock us because, as viewers of this film, we realize that he hardly knows us at all. A trapped, exposed, yet expectant and appraising, even judging, look. In our daily practice, it can be relatively easy to pass through the moment that Truffaut freezes and seeks to burn into us, but Truffaut makes that impossible in the film because, unlike the case of the child in our clinic from whom we will soon move on, we have witnessed the complex regrettable circumstances of Antoine's life that finally converge in this moment. So that when he turns to us for the first and last time in the film, we understand that he is asking, even demanding, to know what we are going to do about what has happened to him. But so are many of the children who look up at us when we walk into the examination room.

To Hear/To Say

Language is one of Truffaut’s deepest preoccupations. All of the four films he made about children examined language in one way or another. His interest in language culminated in “L’Enfant Sauvage” (1969), “The Wild Child,” which explored the origin, development and use of language through the story of a feral child initiated into civilization by a physician trying to teach him to speak. For Truffaut, language offered special solace and retreat from the banality and cruelty of life and, in “The Wild Child,” salvation from the abyss of lost connection with one’s own species. In “The 400 Blows,” as with the children of the Emperor who were never taught language so that they never understood nor were heard by others, Antoine Doinel inhabits a world in which his inner life, his feelings and sufferings are opaque to all, except to us [the audience] [5].

Throughout the film, Antoine engages in numerous petty thefts all connected with language in some way. He steals a pen, a book and a typewriter. When he runs away from home he sleeps in a printing factory. In his last-ditch effort to redeem himself at school he plagiarizes Balzac. The stolen typewriter makes him a ward of the state and plagiarizing Balzac gets him kicked out of school. When asked in his sole session with an analyst why he’s always lying, Antoine replies, “I lie because the truth I tell they don’t believe.” Here Truffaut is exploring a theme which interested him for most of his career, how children are not allowed to express or receive authentic communication [6].

As physicians, we often find ourselves particularly challenged to offer children this opportunity. We see children who have never been read to, or who have never received a kind word or compliment from the mother or father who has brought them to our clinic. We often speak directly to the parent over the head of the child, as if he or she were not present. The message of “The 400 Blows,” as with all of Truffaut’s films, is for us (as it is for other viewers) that this is not good enough. Given the extent to which our patients’ health is so profoundly shaped by their behavior (and the behavior of their parents) outside our presence, and given that our standard medical tools often can do little more than poorly mitigate the effects—such as obesity, mental disease, diabetes—of that behavior, it seems difficult to argue that we don’t have an obligation to at least attempt to communicate more authentically—to model that empathy—with the children in our care during the limited moments and opportunities we have to influence change.

The Environment

At home, Antoine sleeps in a converted closet between two rooms so that every passage of his parents intrudes on him; he is constantly in the way. The kinds of treatment he receives under four roofs—home, school, jail and reform school—are not terribly different from one another [7]. The interiors are all filled with callousness and gloom. The blows in this film are indeed physical; we are aware of how deeply the environments Antoine finds himself in close in on, reach into and strike him from all directions. He seems constantly running through the streets of Paris, from school, home, correctional facilities, parents, teachers and finally to the sea, in a futile effort to escape and in a desperate attempt to save himself.

At one point, after having run away from home, Antoine finds himself in the principal’s office with his mother and his English teacher who, while reaching for explanations for Antoine’s chronic misconduct, blurts out: “maybe it’s in his genes.” The remark lacks subtlety to say the least and may be taken as an accusation since Antoine’s mother, his genetic lineage, is actually present to take the blame. The film came along just six years after Watson and Crick’s landmark discovery of the structure of DNA. Genetic explanations for behavior were in vogue then as they have continued to be ever since.

What this explanation neglects is what “The 400 Blows” so powerfully illustrates in its title and in the pure physicality of each environmental attack—that nurture has as profound a physical effect on who we are as our genes, that nurture becomes as much a part of our bodies and minds as our genetic endowment, hard-wiring us as surely as our genes. Acts of violence and neglect cause new biochemical neuronal connections to be made in our brains, cause other connections to be lost and leave us with real physical scars and disabilities in our minds as well as our bodies.

There is, of course, great resonance in our own experience with this aspect of Truffaut’s masterwork. The medical environment itself is so clearly not designed to make a child feel comfortable, let alone to inculcate hope and well-being. The English teacher's superficial understanding of Antoine and his family finds its echo in the collision of incomprehension between, on the one hand, medical students and residents largely from privileged backgrounds and, on the other, patient populations typically served by teaching hospitals, an incomprehension that can do particular injustice to a child.

To Hope Despite All

In the end, the process by which some transcend their environments is actually as ineluctable as the miraculous achievements of those born with physical or mental disabilities. When we celebrate the achievements of someone who has overcome the limitations of an impoverished background and hold up this individual as a reproving role model to his or her fellows, we are as ridiculous as if we were to hold up a pancreatic cancer survivor as proof that all others with cancer should be able to follow the same path to recovery. At best, and it is not an insubstantial best, the survivor offers hope.

“The 400 Blows” illustrates how hard and necessary it is to focus on hope by showing us how easily and inevitably Antoine’s considerable talents, middle-class resources, friends, acute self-awareness and attempts to escape can be overwhelmed by all-too-common parental and social neglect. From a medical perspective, the film calls for a greater awareness of this reality on our part and for recognition of our power to either add to or form a bulwark against the forces that drive children into despair and sickness—as Antoine was driven to the sea. For Truffaut, as crystalized in Antoine’s final look back at us, it is not just a power, but an obligation to see and to hear children and to find hope and purpose in their beckoning, innocent stare.

References

-

Wright F. "Prescience." In: God’s Silence. Alfred A. Knopf; 2006. Available at: http://www.poems.com/prescwri.htm. Accessed September 22, 2006.

-

Truffaut F. The 400 Blows. [DVD] Criterion Collection. 1959, 2006. Available at: http://www.criterionco.com/asp/release.asp?id=5&eid=286§ion=essay. Accessed September 22, 2006. Originally released as Les Quatre Cent Coups. Paris: Les Films du Carrosse, Sédif Productions; November 16, 1959.

-

Insdorf A. Francois Truffaut. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994:161.

-

Insdorf A. Truffaut, 43.

-

Insdorf, A. “Les Enfants Terribles.” In: Truffaut, 145-173.

-

Insdorf A. Truffaut.

-

Insdorf A. Truffaut, 152-153.