Case

Mrs. Assan took her son to an emergency room in rural North Dakota around dinnertime, shortly after she had come home from work. He had a frequent dry cough but no fever. His symptoms had begun three days before. Although he was uncomfortable and coughed frequently, the boy appeared to be hydrated and not in acute distress.

The ten-year-old boy was insured through North Dakota’s Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) plan. Usually, Mrs. Assan took him to his family doctor, but when she had called the physician’s office earlier that evening, she had been told that the doctor could not fit him in for several days at least. The person with whom she spoke recommended that Mrs. Assan take her son to the emergency room. There are few community health clinics in the area, and even fewer physicians in the area who accepted new Medicaid and CHIP patients. Mrs. Assan did not feel she could wait to have her son seen since his cough continued to get worse day by day.

Upon ER screening, the boy’s status was categorized as nonurgent by a fourth-year medical student, Nadia. Mrs. Assan became angry when she was told that this hospital had recently instituted a policy under which nonurgent patients were sent to the financial desk, asked to pay a screening fee and provided with a list of local clinics. Mrs. Assan was told by the assistant at the financial services desk that she could continue to wait for her son to be seen, but she was discouraged from doing so. The hospital served a large geographic area, and the assistant predicted that the waiting time for the boy on that particular evening would be four to five hours. Mrs. Assan had to work the next day, and she hoped that her son would be able to go to school.

Mrs. Assan didn’t know whether to wait or not. She worried about letting her son’s cough go until his regular doctor could see him. She saw Nadia passing by and asked her what to do. Nadia was torn. On one hand, she thought it would be better for the boy to be seen in a more appropriate primary care setting, preferrably by his own doctor. On the other hand, she understood Mrs. Assan’s concern for her son’s health. A parent with full-time employment could not simply go off to work for “several days at least” while her son was sick at home. But the ER was overwhelmed on the night the Assans were there. Patients had come in with conditions varying from lacerations after a car accident to a slight fever to a suicide attempt. Nadia had been told that under EMTALA (Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act) she must examine the boy if Mrs. Assan requested it, but without his prior health history and because of the overload in the ER, Nadia believed the boy would benefit most from going to another clinic.

Some hospitals have a primary care focus incorporated into their emergency rooms, but the ER the Assans visited did not. All things considered, Nadia did not know what she should recommend to Mrs. Assan.

Commentary

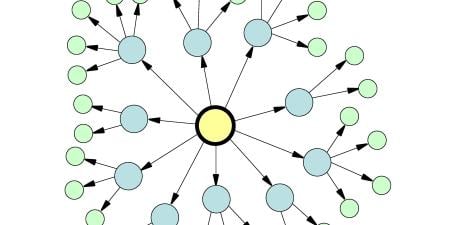

Emergency departments (ED) serve diverse patient populations with a wide variety of needs. There are patients with life-threatening or other emergent conditions, for which the ED is clearly the best source of care; there are patients with urgent but less critical conditions who could potentially be treated in a number of settings, but who choose the ED for a range of reasons. Finally, the ED provides a certain amount of safety-net care, including primary care services, to patients without access to any other source of health care. Estimates vary, but it is thought that between 40 and 80 percent of pediatric visits to EDs are “nonurgent” [1]. Is this a problem? If so, what are its causes and consequences and what can be done about them?

Consequences of Nonurgent ED Use

There are some myths about nonurgent ED use that bear close consideration. The first is that most such visits are “inappropriate,” where appropriateness is defined as the right care provided in the right place at the right time. Whether care provided during an ED visit is the right care in the right place at the right time depends on many factors, including the nature of the problem, the family’s perception of its urgency, the resources available to the patient and family for dealing with it and the ready availability of other sources of quality care at the time it is needed. Studies have shown that, regardless of the criteria used, appropriateness is difficult to determine accurately—either prospectively or retrospectively—and, as a result, many experts have urged that the terms “appropriate” and “inappropriate” be avoided entirely [2].

A second myth is that nonurgent visits interfere with care for sicker patients. ED crowding has become a serious problem in recent years [3], and, while it is tempting to believe that substantial use of EDs for nonurgent care is a contributing factor, the available evidence does not support this belief. According to the American College of Emergency Physicians, “While nonurgent use of the ED is an important policy issue, there is no evidence that it is responsible for ED crowding” [4]. Other factors, particularly a lack of available inpatient beds for patients who require hospitalization, are far greater contributors.

Finally, there is the argument that care in the ED is unnecessarily expensive. This is a contentious issue, with different economic analyses reaching different conclusions [5]. There is some evidence, however, that, given the need for a well-equipped, properly staffed emergency facility to be available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to provide care for those with conditions that need immediate attention, the cost of providing care for additional patients with a nonurgent conditions is relatively small [6].

Still, there may be a financial impact from nonurgent ED visits. Contrary to many assumptions, the majority of nonurgent visits are made by white, insured, middle- and upper-class patients; at the same time, it is true that a disproportionately large percentage of uninsured and disadvantaged patients use the ED for nonurgent visits [7]. A law entitled The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) was passed in 1986 in an effort to prevent hospitals from “dumping” uninsured emergency patients. EMTALA requires EDs to screen and stabilize patients who present for emergency care, regardless of their ability to pay [8]. Hospitals are not compensated for this mandated care to the uninsured, and Medicaid reimbursement is typically inadequate to cover the costs of the screening and testing that the hospitals run. EMTALA may therefore place a financial burden on hospital EDs that see large numbers of uninsured patients with non-urgent conditions. Moreover, a financial burden may be passed on to patients; patients without adequate insurance have a right to be seen, but are still generally responsible for payment. In addition, there is no obligation to prioritize patients with less acute problems, so those with nonurgent complaints may well have prolonged waits which can interfere with work time while more acute patients are being treated.

Another consequence of using the ED for nonurgent care is the potential loss of continuity of care. Pediatrics in particular, emphasizes patients’ having a “medical home,” that is, a place where the child receives the bulk of his or her health care and where the responsibility for coordinating that care is willingly accepted [9]. In addition to potentially weakening the bond between family and physician, when children receive nonemergency treatment in the ED, opportunities may be missed for preventive care and counseling and maintenance treatment for those with chronic medical conditions. Children with asthma, for example, who are frequent users of the ED for acute treatment may be less likely to be placed on and monitored for proper use of controller medications [10]. In this case, it appears that the young Assan has a “medical home,” but one that is not meeting his current need. While referring him to a different primary care clinic that can see him now for the cough may seem an attractive alternative, it may in fact adversely affect his relationship with his current physician.

Reasons for Nonurgent ED Use

Despite the myths, we have seen that there may be actual adverse consequences to going to the ED for nonurgent care, especially for patients and their families. Why, then, does it occur? Many reasons have been discovered during research on the topic. Regardless of their ultimate triage assignment or disposition, most patients believe their problem requires urgent attention. Many patients lack any other source of care. For others, it is a matter of availability or convenience. In this case, for example, Mrs. Assan might be willing to wait for an appointment under different circumstances, but she doesn’t feel as though her son can wait the several days until he can be seen by the primary physician. Convenience may be an important factor; suppose an appointment at the pediatrician’s office means Mrs. Assan must miss a day of work (and pay)? Further, a recent study shows that many patients perceive that the ED provides better quality care [11]. A lack of continuity of care and dissatisfaction with primary care have been shown to lead to greater use of the ED for nonurgent problems [12,13]. It seems clear that most patients who seek nonurgent care at the ED do so because it is the place that is most likely to meet their needs at the time. Even when it is not their first choice, in the fragmented U.S. health care system, the ED is a reliable, available and convenient place where patients with any type of problem can be seen.

What to Do About Nonurgent ED Care

Until 1986, a commonly used solution for EDs was simply to deny care to patients with nonurgent conditions who could not afford to pay. Under EMTALA, however, this practice is illegal. The required medical screening exam is not a simple matter of triage. It includes whatever evaluation is necessary, by a qualified provider and within the capabilities of the hospital, to determine whether a patient is stable. In this case, it is not clear if that obligation has been met, since a medical student would not be considered a “qualified provider” for EMTALA purposes. If Mrs. Assan perceives that she has not been accorded the proper evaluation because of the type of insurance she has, she could file a complaint, leaving the hospital open to substantial penalties if it is found to be out of compliance.

Financial Consideration

In recent years, hospitals have begun to insist on payment up front after the minimum medical screen, as in this case, with a goal of minimizing the cost of the encounter and, more importantly, to discourage future use [14]. Whether this is successful or not remains to be determined. Besides, for most nonurgent conditions, once the medical screen has adequately determined that the problem is not an emergency, most of the work has been done and there may be relatively little additional cost. Referring patients away without making alternative arrangements may also violate the ethical obligation of emergency physicians “to act as advocates for the health needs of indigent patients” [14].

What Should Nadia Do?

This situation is a difficult one. However, Nadia’s obligation is to the patient, not the hospital. She should attempt to elucidate better the Assans’ relationship with their primary care physician. Is it someone in whom they have confidence and trust and who is normally available when needed, or is there a pattern of unmet needs? If the former is true, maintaining that relationship is important, while help in finding a different “medical home” might be useful in the latter circumstance. If Mrs. Assan is primarily concerned about the screening fee, consulting a social worker or a financial service representative may be helpful. Finally, if the only reasonable way for the boy’s problem to be addressed is for him to be seen and treated in the ED, that decision should be supported. We should never make families feel guilty about taking up our time or crowding our ED when they are in need.

It is increasingly clear that nonurgent use of EDs is a societal problem, one that will not be solved through punitive measures against patients and families, or by shifting the problem to other providers. If the Assan family's plight moves Nadia, she should advocate for systematic change in the way health care is delivered.

References

- Mistry RD, Hoffmann RG, Yauck JS, Brousseau DC. Association between parental and childhood emergency department utilization. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):147-151.

-

Abbuhl SB, Lowe RA. The inappropriateness of “appropriateness.” Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(3):189-191.

-

Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System Board on Health Care Services. Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, Institute of Medicine; In Press.

-

American College of Emergency Physicians. Responding To Emergency Department Crowding: A Guidebook for Chapters. Available at: http://www.acep.org/NR/rdonlyres/F816F22E-1E8A-43BC-8357-5F6DC966C349/0/edCrowdingReport.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2006.

- Kellerman AL. Calculating the cost of emergency care. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(5):491-492.

- Williams RM. The costs of visits to emergency departments. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(10):642-646.

- Lowe RA, Localio AR, Schwarz DF, et al. Association between primary care practice characteristics and emergency department use in a Medicaid managed care organization. Med Care. 2005;43(8):792-800.

-

American College of Emergency Physicians. EMTALA. Available at: http://www.acep.org/webportal/PatientsConsumers/critissues/UninsuredUnderinsured/emtala.htm. Accessed October 4, 2006.

- Starfield B, Shi L. The medical home, access to care, and insurance: a review of evidence. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 Suppl):1493-1498.

- Cydulka RK, Tamayo-Sarver JH, Wolf C, Herrick E, Gress S. Inadequate follow-up controller medications among patients with asthma who visit the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(4):316-312.

- Ragin DF, Hwang U, Cydulka RK, et al. Reasons for using the emergency department: results of the EMPATH study. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(12):1158-1166.

-

Brousseau DC, Bergholte J, Gorelick MH. Decreased primary care satisfaction is associated with nonurgent emergency department utilization [abstract]. Pediatr Res. 2003;53(4):267A.

- Brousseau DC, Meurer JR, Isenberg ML, Kuhn EM, Gorelick MH. The association between infant continuity of care and pediatric emergency department utilization. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):738-741.

- Bitterman RA. EMTALA and the ethical delivery of hospital emergency services. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2006;24(3):557-577.