Case

"This next woman, Ms. West…" Dr. Young said, sighing, his voice trailing off. "...well, it's a sad situation." Dr. Young paused outside the room with Bill, a third-year medical student.

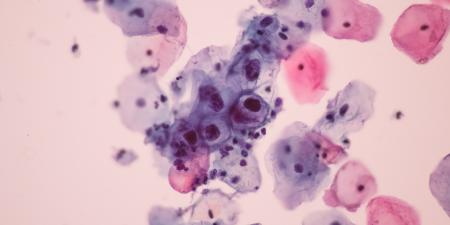

"I treated her for stage III cervical cancer two years ago, and I've been following her ever since. Her treatment went very well. We thought we had gotten rid of her cancer, but her latest bone scan revealed a few areas in her thoracic spine that are highly suspicious for metastases. It doesn't look good. I asked her to come in so we can discuss the latest scan.

"The thing is," Dr. Young continued, "she lives alone and doesn't seem to have many friends or much social support. You'll see in her chart that she has suffered from major depression ever since her cancer diagnosis. So we have to be careful not to upset her too much with this development. I'm afraid her depression could affect her chances for survival."

Dr. Young entered the room and Bill followed close behind. Ms. West sat slumped in a chair in the corner, looking much older than her 42 years.

"It must be really bad news if you asked me to come down here in person," she said, without lifting her gaze from the floor. "Am I going to die?"

"C'mon, don't talk like that," Dr. Young replied trying to sound encouraging. "I asked you to come in because I'm a bit concerned about your latest scan results. I'll need to run a few more tests, and most likely you'll have to be treated again. But we have some effective treatment options, and we're going to take good care of you here, just like we did two years ago. My student Bill is going to examine you, if that's okay, and I'll be back to chat in a couple of minutes." Dr. Young smiled warmly and stepped out of the room, leaving Bill and Ms. West alone.

"Wow," she said, finally glancing up towards Bill. "I thought I was really in for some bad news, but it looks like I'm going to be OK after all, right?"

Commentary

In this case Dr. Young needs to communicate bad news to Ms. West. He is concerned that her previous depression will worsen with this news and that the depression will have a negative impact on her chances for survival. This situation will test the relationship between Dr. Young and Ms. West, since Dr. Young must communicate the test findings clearly and honestly while assuring Ms. West of continuity of care and presenting her with the options available for treatment. In the middle of the established relationship between Dr. Young and Ms. West, is Bill, the third-year medical student who is placed in a difficult position. Bill has been left alone with Ms. West minutes after she has heard that Dr. Young is "a bit concerned about…latest scan results." She has not yet been told what those findings were or what they mean. When Ms. West asks if she is going to be all right, Bill is faced with a tough question—one that would challenge even an experienced physician. As a medical student, Bill has greater cause for distress than Dr. Young. Dr. Young has to be thinking about how the interaction will affect his relationship with Ms. West; Bill must figure out how to be honest with Ms. West while explaining things the way he believes Dr. Young would want him to.

Communication between Patients and Physicians

Let us consider the principles that should guide the communication between patient and physician and then those that should guide the patient-student interaction. The exchange between a physician and a patient should be honest and complete. The disclosure of bad news should be part of an ongoing dialogue rather than just a single interaction. When communicating bad news to patients, physicians should strive to acknowledge the inherent uncertainties of any medical prognostication, as well as the fear and uncertainty that the patient is experiencing. The doctor should emphasize what options are available both immediately and down the road for the patient and should affirm that he or she will stick with the patient throughout the illness and the treatment. These are reassurances that only the physician—and not a student—can give. In the present case, Dr. Young initiated this important component of communicating bad news when he stated, "we have some effective treatment options for you, and we're going to take good care of you…" In relaying these messages, physicians should never lie to a patient in an attempt to protect his or her "hope." Certainly no doctor should be so paternalistic as to believe that he or she fully understands what will give a patient a sense of hope.

Communication between Patients and Students

If we now consider what principles should guide the patient and student discussion, we readily see that the same principles apply. The student should acknowledge more uncertainty, however, since he or she will almost always know less about the implications of the bad news than the attending physician does. One additional guideline traditionally observed between students and faculty is that the student should not be the first to deliver bad news to a patient. Why does this seem to be so widely accepted? Doctors and patients both understand that how information is transmitted is important, and the way in which patients first hear bad news can have an impact on how they react to it.

The Case at Hand

After such good initial communication between Dr. Young and Ms. West, Dr. Young abruptly left the room, placing Bill in a situation where he was being pressured to be the first to disclose the test findings and prognosis to Ms. West. This role is one that Bill is understandably anxious to avoid.

What could Dr. Young have done to spare Bill this awkward encounter? First, he could have discussed the recent results more fully with Ms. West before leaving Bill to complete the physical examination. This would have allowed her to hear all of the information and to ask questions of Dr. Young and later of Bill. Such an approach would help ensure that Ms. West received the benefit of a physician's knowledge, so that the student would not be asked the toughest questions.

Another possible approach that would free Bill from pressure to lie to, or at least be vague with, Ms. West would be for Dr. Young to withhold information from Bill until after he has given Ms. West the news. This would save Bill from having to wonder what the patient should be told. What Bill does not know, he cannot tell, so there is no deception in not sharing information with Ms. West.

Given the situation as described in the case, however, what is Bill to do? First, he should be honest; he has been told little about the test results and what implications they might have. It is often best for the student to simply repeat what the physician has already said to the patient. In the current case, Dr. Young has said that further treatment is most likely necessary and that there are some effective treatment options. A key role for Bill in his interaction with Ms. West is to reinforce these statements.

Perhaps the most helpful thing that Bill can do during his limited interaction with Ms. West is make clear that he is on her side. An alliance with a patient is one relationship that students can readily encourage. Bill can foster this partnership by being open with Ms. West and pointing out that both of them have less knowledge about her recent scan results and its implications than Dr. Young. If Ms. West asks Bill a question that he cannot answer, such as, "It looks like I'm going to be OK, right?" Bill should assert that it is a critical question but that he really doesn't know enough to answer. Suggesting that the question be asked of Dr. Young puts Bill and Ms. West together on a fact-finding quest. Students can often help patients to understand what questions need to be asked even when they themselves do not have the answers. They can also help patients clarify which concerns to bring up in future discussions with the physician. In this role, Bill could work to develop a stronger relationship with Ms. West while not giving medical information he is not fully prepared to provide.

This case illustrates how the relationships that develop between medical students and patients are similar but distinct from those between patients and physicians. It is valuable for physicians and students to be cognizant of the challenges of the patient-student relationship so that students can acquire the skills they need to be more comfortable in the relationship and, most importantly, even helpful to patients.