As a newly minted physician receiving my residency training at a large, urban, mostly charity-driven hospital in Dallas, I spend much of my day treating recent immigrants from south of our border with Mexico. I have great affection for my patients and, as the cliche goes, I feel as though I get more from them during our time together than they receive from my care. They remind me daily of the importance of family and of living a good and honest life—basic truths that can become lost in the midst of long hours on call and other demands of our profession. In this edition of the Virtual Mentor I hope to illuminate some of the ethical challenges physicians confront when working with patients who are immigrants.

According to United States Census projections, there are 37.9 million immigrants in the United States—nearly 1 in 8 members of our population—and nearly 1 in 3 are undocumented [1]. The growth of the immigrant population has been exponential. Since 2000, 10.3 million people are believed to have immigrated, and more than half of those (5.6 million) are estimated to have done so illegally [2]. One-third of all immigrants lack health insurance—approximately two-and-a-half times the number of native-born U.S. citizens who are uninsured—and many of them seek care at hospitals like mine [1].

Over the past decade, as the immigrant population has increased, the federal government has reacted by restricting access to Medicaid and other social service programs including SCHIP (State Children's Health Insurance Program) [3]. In some instances, states have stepped in to fill the gap, providing care—some preventive, some emergency—to immigrants without requiring proof of citizenship [4]. In Texas, the state's attorney general determined that certain preventive medical services could no longer be provided to illegal immigrants and that physicians would be required to obtain proof of citizenship before treating any patients [5]. Some counties adopted the attorney general's interpretation of the federal legislation; others did not. In Virtual Mentor's first clinical case, Patricia Evans discusses the debate over the attorney general's ruling and the ethical ramifications of forcing a physician to act as an agent of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration service (formerly the INS) in his or her clinic.

The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, commonly known as the Welfare Reform act [3], along with other legislation, had a chilling effect on access to care not only for the undocumented, but also for legal immigrants and native-born citizens [4]. In her policy forum article, Laura Hermer discusses the obstacles to obtaining adequate reimbursement from different funding sources for care of immigrants.

Despite decreases in coverage of immigrant health care in recent years, proponents of more stringent immigration restrictions assert that hordes of "illegals" are flooding across the border to "steal" medical care [6]. In fact, however, an Immigration Policy Center report found that, in 1998 immigrants (both legal and undocumented) received about $1,139 per capita in health care, compared to $2,546 for native-born residents. Although immigrants comprised 10 percent of the U.S. population at that time, they accounted for only 8 percent of U.S. health care costs [7]. With regard to illegal immigrants in particular, a study of Emergency Medicaid use in North Carolina, reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association, showed that, although 99 percent of those whose care was reimbursed under Emergency Medicaid were undocumented immigrants, that spending represented only 1 percent of total expenditures by Medicaid in that state. Anjana Lal analyzes this JAMA article in her journal discussion.

Immigration reform proponents frequently criticize Hispanic immigrants for failing to assimilate, pointing specifically to their failure to achieve proficiency in English. I am fluent in Spanish, and I speak to most of my patients in their native tongue. Indeed, I can pass an entire day in clinic rarely speaking any English. In the medical education section, Katherine Clarridge, Ernest Fischer, Andrea Quintana, and James Wagner consider whether Spanish should become a requirement in the medical school curriculum and whether such a requirement would even be beneficial.

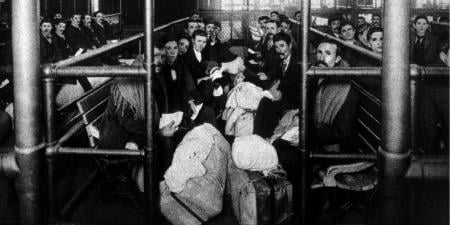

Another argument advanced in support of tougher border controls and other immigration reforms is the fear of the spread of disease. Reformers point to recent increases in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis as an example and argue that we should tighten borders and re-institute Ellis Island-style health exams [6]. As Alison Bateman-House and Amy Fairchild explain in their history of medicine article, Ellis Island health exams looked for more than infectious disease and had the potential to discriminate against certain ethnicities and those with physical deformities or weaknesses.

Jason Yeh and Jeanne Sheffield explore another aspect of immigrant medicine. In the clinical pearl, they write about the rise in diseases that affect immigrants but are relatively uncommon in the United States where sanitation and inoculation programs are well established. In our hospital population, neurocystercicosis, generally considered a rare neurological disorder and cause of seizures, is fairly common. Yeh and Sheffield discuss the duty of physicians treating predominantly immigrant populations to educate themselves about conditions that are rare in their practice specialty but more common in their patient population.

As mentioned above, immigrants, despite claims that they use health services disproportionately, have limited access to care in the United States [7]. In the medicine and society article, Charu Gupta points to the disparity between immigrants' access to organ transplantation and their contribution to the pool of available organs. By contrast, Reza Yassari writes that immigrants with rare disorders might be offered treatment because American programs welcome the opportunity to perform advanced procedures. The motivations for the American hospital may include media attention and enhanced reputation. In these situations, patients benefit greatly from the initial procedure, which is usually provided free of cost, but are then expected to provide for their own expensive follow-up care [8]. Yassari asks the complex question of what duties arise when physicians initiate care for patients from countries where that type of care is not available.

In a somewhat similar vein, Peter Bundred addresses the conundrum faced by many residency programs that are unable to fill all their training positions but have qualified foreign applicants. This constitutes an ethical conflict because foreign graduates are unlikely to return to their home countries, many of which need doctors, after their training, choosing instead to remain in the United States. Bundred describes the responsibilities residency directors might consider when recruiting foreign medical graduates, responsibilities both to their own programs and to the populace of the trainee's country of origin who will be deprived of a well-trained physician despite a great need.

Returning to my opening statement, I have always received more from my patients than I believe I have been able to give them. I have found this especially true with members of the Hispanic population who boast a rich cultural tradition of alternative medicine, as described by medical student Kimberly Aparicio. As physicians, we must treat all of our patients with dignity and respect and never make them feel as if we are doing them a "favor."

I hope this edition of Virtual Mentor succeeds in addressing some of the primary ethical disputes inherent in the medical treatment of the immigrant population. As a society that relies heavily on an immigrant labor force, we have a duty to provide members of that workforce with basic medical care. Defining this level of care is difficult, as illustrated by the pieces herein. Ultimately, to quote Ron Anderson, who writes eloquently about this duty in his op-ed, as physicians we are "left with a human being...who needs [our] help" [9]. It would be unethical to turn our backs.

References

-

US Census Bureau. FactFinder. http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/main.html?_lang=en. Accessed March 20, 2008.

-

Department of Homeland Security. Yearbook of immigration statistics. http://www.dhs.gov/ximgtn/statistics/publications/yearbook.shtm. Accessed March 20, 2008.

-

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. HR 3734, 104th Cong, 2nd Sess (1996). http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=104_cong_bills&docid=f:h3734enr.txt.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2008.

-

Sonfield A. The impact of anti-immigrant policy on publicly subsidized reproductive health care. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2007;10(1):7-11. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/gpr/10/1/gpr100107.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2008.

-

Yardley J. Immigrants' medical care is focus of Texas dispute. New York Times. August 12, 2001.

-

Cosman MP. Illegal aliens and American medicine. Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons. 2005;10(1):6-10. http://www.jpands.org/vol10no1/cosman.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2008.

- Mohanty SA. Unequal access: immigrants and U.S. health care. Immigration Policy In Focus. 2006;5(5):1-7.

-

Santos F. Fairy tale ending eludes separated twins. New York Times. November 4, 2007.

-

Jacobson S. Parkland will treat all moms-to-be. Dallas Morning News. June 12, 2006. http://www.dallasnews.com/sharedcontent/dws/news/localnews/stories/061206dnmetmoms.d9b9669.html. Accessed March 19, 2008.