Numerous surveys have demonstrated that the American public is affected by bias against people who are overweight and obese [1-3]. Physicians, too, express these biases. A survey involving a nationally representative sample of primary care physicians revealed that, not only did more than half of respondents think that patients who are obese were awkward and unattractive, but more than 50 percent believed that they would be noncompliant with treatment [4]. One-third thought of them as “weak-willed” and “lazy.” Another study found that as patients’ weight increased, physicians reported having less patience, less faith in patients’ ability to comply with treatment, and less desire to help them [5]. Other studies have added to the evidence that bias against patients who are obese is common in health care settings [6].

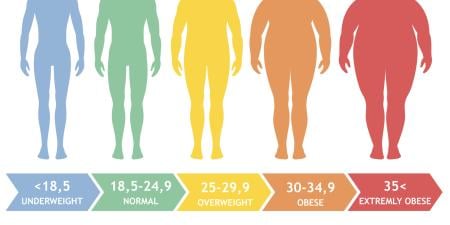

These prejudices are somewhat peculiar, given the fact that the majority of Americans are themselves overweight or obese. Many who are overweight, however, do not perceive any problems in their individual circumstances. In a study of 6,000 people, 8 percent of people who were obese thought they were healthy and did not need to lose weight, despite the fact that 35 percent had high blood pressure, 15 percent had dyslipidemia, and 14 percent were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Pejorative connotations are ascribed to obese folks “out there,” not oneself.

This prejudice may be partly due to how the media portray people who are obese. Greenberg et al. reported on their findings of television actors’ BMI after analyzing 5 episodes of the top 10 prime time shows [7]. In comparing television actors’ BMI to that of the American public, they found that only 25 percent of men on television were overweight or obese, compared to almost 60 percent of American men. The statistics are even more staggering for women. Almost 90 percent of women on TV were at or below normal weight, compared to only 50 percent of American women.

Popular television shows that include people who are obese portray them either as comedic, lonely characters, or freaks. On The Drew Carey Show, the main character often joked about and expressed disappointment about his weight; his main “nemesis,” Mimi, was portrayed as being unattractive partially because of her weight (though also for reasons having to do with her personality and fashion choices). Ugly Betty focuses on an overweight young woman who, although she is comfortable with her weight, is often mocked for her size and awkwardness. On Chuck, Fernando is not only a nerd, but also a “fat nerd” who has little, if any, real character development. And who can forget Roseanne, who was loud, obnoxious, and slovenly? Rarely if ever are they romantic leads, successful lawyers or doctors, or action stars. Flip through the numerous reality shows on television where women are battling for a modeling contract. There is often considerable negative discussion about the one or two contestants who have “extra weight” and are therefore lacking what is perceived as a model’s body, and only one plus-size model has won any such contest. Keep in mind that the average American adult is overweight or obese, so the person at normal weight is actually in the minority. There are many successful people who are overweight and obese in today’s society, but that is not reflected in popular entertainment.

It is hard to discuss media portrayal of people who are overweight without mentioning The Biggest Loser, a highly successful television program and publishing enterprise. This type of show—that selects participants on the basis of a particular feature—does not focus on the typical person. Most people who are overweight are not morbidly obese, nor do they have armies of personal trainers, dietitians, and life coaches. The Biggest Loser promotes the perception that obesity is caused by individual failure rather than a mixture of individual, environment, and genetic sources.

There is good news. The media have the potential to promote health and discourage prejudice. The current negative portrayal of obesity in media seems analogous to the portrayal of homosexuality in the recent past. Remember when gay characters were either drag queens or overtly promiscuous? For instance, Jack from Will and Grace (itself considered a step up from previous portrayals of homosexuality, as it was one of the first highly popular sitcoms with gay protagonists) was campy, superficial, and sex-crazed. Such portrayals helped to promote stereotypes of gay men and women. Some debate remains about current portrayals, but views of same-sex relationships, especially, have improved dramatically over the last decade. Examples include episodes from ABC’s Brothers and Sisters, which show a married relationship between two men in a manner similar to the portrayal of heterosexual relationships, and the Fox network’s Glee, which features Kurt, a glee club member who announces to his father that he is gay. His father’s response is supportive and nonjudgmental. This is a considerable improvement from the time when gay characters were either flamboyant, overly promiscuous, or simply invisible.

There is no doubt that the media can play an important role in educating the public on health topics. According to a CDC survey of U.S. residents who watch television at least twice weekly, more than half of the respondents believed that health information presented on TV is accurate, and 26 percent cited prime-time TV programs as one of their top three sources for health information [8]. Just last year, a survey of 550 moms with at least one child under 18 years of age listed pediatricians as the most trusted source of health information—but this was followed closely by evening news, Internet searches, Web sites, and morning talk shows [9].

The challenge for media is to provide entertainment to viewers. If a news outlet wants to schedule programming about obesity or healthy living, it almost has to do a story about cutting a 500-pound woman out of her home in order to get people to tune in. It is difficult to get viewers to tune in for programming about lifestyle, but not impossible. Many folks are beginning to use the terms “edutainment” or “medutainment”—trying to create shows that are entertaining but also educational, especially on medical or health matters. Several years ago, a popular soap opera had a subplot about a character infected with the HIV virus [10]. At that time, 4.5 million viewers watched soap operas. The network displayed the National STD and AIDS hotline toll-free numbers after two episodes. The number of calls during the 1-hour time slots just after the broadcast rose dramatically, nearly 10-fold. Although soap opera viewing is down, and there are fewer soap operas in production, 53 percent of all women who report viewing soap operas regularly, 56 percent of Hispanic women who view soap operas, and 69 percent of African American women who view soap operas recently responded that they had learned something about diseases or how to prevent them from soap operas in the previous year [11]. The media can be a force for good.

Media can and should be used to address the obesity epidemic. The media can play a pivotal role in providing credible and evidence-based information to increase health literacy, help people live healthy lives, and decrease discrimination against people who are overweight or obese.

References

-

Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. In: Bray G, Bouchard C, eds. Handbook of Obesity: Clinical Applications. 3rd ed. New York: Informa Healthcare USA; 2008:81-89.

-

Lie D. Cases in Health Disparities: bias against the obese patient and approaches for managing it. Medscape Today. February 17, 2010. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/716744_2. Accessed March 8, 2010.

-

Brownell KD, Puhl RM. Stigma and discrimination in weight management and obesity. Permanente J. 2003; 7 Suppl:16-18.

- Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, et al. Primary care physicians’ attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obes Res. 2003;11(10):1168-1177.

- Hebl MR, Xu J. Weighing the care: physicians’ reactions to the size of a patient. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(8):1246-1252.

- Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(10):1802-1815.

- Greenberg BS, Eastin M, Hofschire L, et al. Portrayals of overweight and obese individuals on commercial television. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1342-1348.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000 Healthstyles Survey executive summary: prime time viewers and health information. http://www.cdc.gov/healthmarketing/entertainment_education/2000Survey.htm. Accessed March 8, 2010.

-

New survey reveals moms’ media habits [news release]. Marketing to Moms Coalition; September 18, 2008.

- O’Leary A, Kennedy M, Beck V, et al. Increases in calls to the CDC’s National STD and AIDS hotline following AIDS-related episodes in a soap opera. J Commun. 2004;54(2):287-301.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999 Healthstyles Survey executive summary: soap opera viewers and health information.