When a “foreign” element is introduced into the medical context, it can challenge expectations, assumptions, and even procedures. That element can be a patient or doctor from another country or culture, a foreign language, or even a medical condition that is alien to traditional medical approaches. And for patients, of course, the very experience of being ill can be utterly foreign and destabilizing. This month’s issue of Virtual Mentor explores what happens when these unfamiliar elements appear on the medical scene.

The most obvious “foreigner” is the foreign patient. Even more uninitiated in the ways of our health care system than the average American, this person may have different expectations of medicine than native-born patients or no language in common with the health care team. As Kirk L. Smith, MD, PhD, points out in his case commentary, many of the shared assumptions that ease communication and interaction between health care professionals and patients who “belong” to the same country cannot be counted upon in an encounter between people from different countries.

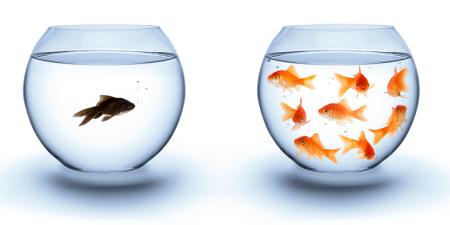

Those who are not native-born but are no longer mere visitors are immigrants. Tension can surround the degree to which immigrants belong in their chosen countries. In the American medical system, much of that tension manifests itself in debates about whether and when citizens of other countries become entitled to publicly funded medical care in the United States. In the health law section, legal editor Valarie Blake, JD, MA, discusses recent controversies over the citizenship requirements for Medicaid. Arturo Vargas Bustamante, PhD, and Philip J. Van der Wees, PhD, review current and needed efforts to integrate immigrants, both documented and undocumented, into U.S. health care, with compassion and cultural sensitivity. This month’s excerpt from the AMA Code of Medical Ethics gives further guidance on bridging culture- and race-based care disparities.

Of course, patients aren’t the only immigrants involved in the medical system. International medical graduates play important roles in American health care, particularly in underserved areas, but immigration policies hamper their ability to do so, Nyapati R. Rao, MD, MS, argues in his policy forum essay. Even when they’re employed in the U.S., foreign doctors may have to contend with the assumptions, fears, and prejudices of patients who are uncomfortable with them. Amit Chakrabarty, MD, MS, FRCS, recommends actions physicians can take to assure patients can listen and participate effectively when communicating with health care professionals who have a different first language or ethnic background than they do. Moreover, while making assumptions may be natural and understandable, it is still often counterproductive. In his medicine and society essay, Jing-Bao Nie, BMed, MMed, MA, PhD, exposes the fallacy of dichotomizing disparate cultures, when in fact they may have more in common than meets the eye.

Less obviously “foreign,” but still very much so, are medical conditions that confound ingrained ways of thinking about and responding to illness. David Edelberg, MD, describes the ways in which the symptoms, test results, and patient behavior that accompany fibromyalgia challenge medicine’s standard operating procedure and urges openness toward types of illness that don’t gratify normal medical expectations.

The most unfamiliar, alienating element of all is the experience of being sick. Managing editor Faith L. Lagay, PhD, and digital media editor Todd Ferguson, PhD, explore the experience of being ill through philosophy and literature. This, above all, urges compassion for all patients and conditions, whether they subvert expectations or not.