A problem that has bedeviled both medical law and medical ethics for decades concerns the scope of risk-related information that a health professional should provide to patients, especially when that information involves the health professional’s experience and success rates with a certain procedure. For example, I take a rather perverse delight in provoking medical students with the following line of questioning:

“How do you determine what risks you’re going to disclose to a patient?”

“You should disclose the risks a reasonable patient would most likely want to know about in making a treatment decision.”

“So, if I had a piece of information that I thought would be likely to influence a patient’s decision one way or another, then you’re saying that I should disclose that to the patient?”

“Yes, absolutely.”

“How many of you think that a physician’s previous experience doing a procedure—as in how many times he or she has performed the procedure, what are his or her comparative outcomes, complication and success rates, etc., etc.—is something that the average patient would likely want to know about?”

Numerous hands go up.

“So, let me ask you this: If you were a patient in a hospital awaiting a procedure, and I was your physician, but I introduced my resident to you and told you that he or she was going to do most of that procedure, how many of you would want to know about this resident’s previous experience doing that procedure? In fact, if this resident had never done this procedure before so that you were going to be his or her first patient, how many of you would want to know that?”

At this point, students begin to squirm, chuckle, and look at one another. Some hands hesitantly go up. So as to capitalize on their distress, I drive the question home:

“So, if you say that a health professional’s previous experience is something that the average, reasonable patient would want to know about, then isn’t the attending physician ethically obliged to disclose to the patient that this will be the resident’s first time doing this procedure? Let me see a show of hands. How many of you believe that the attending should straightforwardly tell the patient that this is the resident’s first time?”

And, usually, very few hands go up, which I then follow with:

“So, aren’t you contradicting yourselves? One the one hand, you say patients have the right to know this information because it would be material to their decision making. But, on the other hand, many of you are now saying that the physician shouldn’t disclose it, at least not at the start.”

And here, some students will offer a utilitarian argument in their defense: “But students have to be trained. If we routinely disclosed, ‘I’m doing this for the first or second time,’ patients would refuse to allow us to treat them and we’d never learn.” But that response implies that the clinicians’ learning needs trump the patient’s right to informed consent, which won’t do in the patient-centered ethics espoused in the United States. Nevertheless, we simply must train our health professionals as best we can, which leaves my students stewing over this quandary (although I suspect they adapt by ultimately choosing not to think too hard about the patient’s right to know). The recent history of neurosurgery provides an illustrative example of the quandary in the case of Johnson v. Kokemoor.

Johnson v. Kokemoor

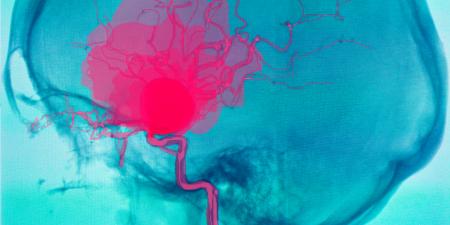

The leading legal case in neurosurgery that addresses this issue is Johnson v. Kokemoor [1]. It’s an excellent teaching case that involved a patient, Donna Johnson, who underwent a CT scan to determine the cause of her headaches. The scan revealed an enlarging, basilar bifurcating aneurysm, which prompted Ms. Johnson to visit the defendant, Richard Kokemoor, a neurosurgeon practicing in the Chippewa Falls area of Wisconsin. Dr. Kokemoor clipped Ms. Johnson’s aneurysm in October of 1990. The operation left her unable to walk or control her bowel and bladder movements, and she experienced some impairment of her vision, speech, and upper body coordination [1].

In her lawsuit, Ms. Johnson did not allege that Dr. Kokemoor was negligent in performing the procedure. Rather, she claimed that she was deceived by his allegedly exaggerating both her need for surgery and his experience in clipping basilar bifurcating aneurysms. Specifically, when Ms. Johnson asked Dr. Kokemoor about his previous experience, “he replied that he had performed the surgery she required ‘several’ times; asked what he meant by ‘several,’ the defendant said ‘dozens’ and ‘lots of times’” [2]. In fact, during his residency, Kokemoor had performed 30 aneurysm surgeries, but all of them were anterior circulation aneurysms. Since his residency, Kokemoor had done only two basilar bifurcation aneurysms and had never operated on a large one like Donna Johnson’s. Ms. Johnson contended that, had she known the truth about Dr. Kokemoor’s lack of experience performing this procedure, she would have had the surgery done elsewhere and by a more experienced neurosurgeon.

This case was largely about whether or not Wisconsin law allowed Ms. Johnson to introduce evidence at trial that Dr. Kokemoor had violated his informed consent obligations by failing to describe accurately his relative lack of experience with the surgery in question. Dr. Kokemoor argued that the informed consent law in Wisconsin only required the usual listing of risks and benefits, procedural descriptions and explanations, “likely outcomes” as they are nationally known, and so forth. He vehemently contended that no physician, in Wisconsin at least, was obligated to reveal the extent of his or her performance experience as a risk factor associated with a particular treatment.

America is the land of the free and the brave, however, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court saw it Ms. Johnson’s way. The court noted that, in Wisconsin as in most states, the standard that physicians must use to determine whether a risk should or shouldn’t be disclosed is that of a reasonable person:

What a physician must disclose is contingent upon what, under the circumstances of a given case, a reasonable person in the patient’s position would need to know in order to make an intelligent and informed decision… [3]. A reasonable person in the plaintiff’s position would have considered such information (i.e., information relating to provider-specific risk) material in making an intelligent and informed decision about the surgery [4].

And so the ruling was handed down: patients having surgeries performed by physicians licensed in Wisconsin can regard their treating physician’s degree of experience as a risk factor like any other risk variable such as the rate of postsurgical infection or exacerbation of a comorbidity. While it’s hard to imagine many Wisconsin physicians being thrilled with the court’s decision, most surgeons would probably agree that a physician’s degree of experience with a complex procedure will inevitably be a correlational, if not a causal, factor in the outcomes of his or her surgeries [5]. As Donna Johnson’s expert witnesses opined on her behalf, even the best, most experienced neurosurgeons faced with clipping an aneurysm like hers would anticipate a morbidity and mortality probability of around 10 to 15 percent, while inexperienced physicians like Kokemoor could anticipate a probability of around 20 to 30 percent.

The Lessons of Kokemoor

I believe there are a number of points to take from this case. If the informed consent conversations between Ms. Johnson and Dr. Kokemoor really transpired as they were reported in the court’s decision, then Kokemoor indeed dissembled or “fudged” when he reported having done “lots” or “dozens” of aneurysm surgeries like hers. But this may not be uncommon. Some clinicians tell me they respond with, “Oh, I’ve had lots of experience with that intervention” when asked by patients, even though their “experience” amounts to having observed others doing it. A problem with medical conversations is that there’s often too much wiggle room for clinicians to obfuscate or cleverly respond to a patient’s queries in self-serving ways.

Another, underdiscussed aspect of this problem is the way a patient’s refusing a particular clinician’s services because of the latter’s lack of experience constitutes a psychological blow to the clinician. The clinician feels rejected; he or she is deemed inadequate by the very person whose trust and respect the clinician craves. So clinicians may be tempted to inflate their experience and confidence to compensate for their insecurities.

Still another problem is that medical training programs don’t prepare students for these self-esteem threats, which issue not only from patients’ electing to find more experienced clinicians but also from disappointing outcomes, relationally challenging patients, commission of errors, relentless demands to meet productivity quotas, and so on [6].

We may nevertheless be at the beginning of a new era in the evolution of informed consent conversations, in which health professionals can absorb the lessons of Kokemoor with greater emotional maturity and a deeper appreciation of the “patient-centered” perspective than ever before. Obviously, we must respect our patients’ right to informed consent, while they in turn should respect that health professionals need to learn the art. Indeed, if health professionals, especially during their training years, were reasonably honest with their patients about their lack of experience in performing procedures, they might well find that some patients are not nearly so deterred by that inexperience as one might think, as long as less experienced clinicians are tutored or assisted by more experienced ones. Perhaps Dr. Kokemoor should have availed himself of more experience by assisting more seasoned neurosurgeons in performing bifurcating basilar aneurysms, and certainly he should have done so before representing himself to Donna Johnson as having performed “dozens.”

Economists, incidentally, would have a ready solution to this entire problem: the inexperienced surgeon should reveal his inexperience but charge substantially less for the procedure, just the way numerous but inexperienced professionals from other professions do. Although this arrangement may sound like another depressing example of turning the patient-doctor relationship into a marketplace transaction, it is a virtual certainty that various patients and their insurance companies would find it appealing, as exemplified by the phenomenon of medical tourism, in which patients travel to the other side of the world for less expensive medical care. Note, however, that this economic model would nevertheless insist on a truthful disclosure of the physician’s level of experience because patients (as buyers) have a right to know the nature of what they are purchasing. Consequently, as the physician’s level of experience is a crucial factor in this purchasing decision, he or she would be obligated to disclose that experience in a way that would inform what patients or their insurers would be willing to pay.

These kinds of musings underline, I think, what informed consent and all the rest of our familiar ethical challenges have always been: social experiments conducted by various groups of human beings in pursuing what they believe to be the best state of affairs reasonably possible. We should remind ourselves that the famous Schloendorff decision [7], which began the historical turn toward acknowledging a patient’s right to control what happens to him or her in surgery, is now a century old. We continue to grapple with the changes and risks engendered by advanced medical technologies—like the ability to clip large, bifurcating basilar aneurysms. And we continue to witness and treat a more educated and, often, skeptical population of health care consumers, who will be disappointed and angry with physicians who offer less than truthful representations about their conditions and available care. Obviously, our moral intuitions and practices must keep pace with technological progress, and one hopes that cases like Kokemoor will inspire students, medical faculty, the medical community, and the general public to strategize ways to accommodate the competing demands of adequately training our future health professionals without sacrificing any of our patient-centered obligations.

References

-

Johnson v Kokemoor, 199 Wis2d 615, 545 NW2d 495 (1996). http://biotech.law.lsu.edu/cases/consent/kokemoor.htm. Accessed November 25, 2014.

-

Johnson v Kokemoor, 23.

-

Johnson v Kokemoor, 51.

-

Johnson v Kokemoor, 55.

- Gawande A. Personal best. The New Yorker. 2011;87(30):44-53.

-

Banja J. Medical Errors and Medical Narcissism. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2004.

-

Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, 211 NY 125, 105 NE 92 (NY Ct App 1914).