After physicians complete residency or fellowship, they apply to medical specialty boards for board certification. For example, anesthesiologists will apply to the American Board of Anesthesiology (ABA) for specialty board certification in anesthesiology. Diplomates, which is what board-certified physicians are called, may undergo further training to receive subspecialty board certification from the ABA in critical care medicine, hospice and palliative medicine, pain medicine, pediatric anesthesiology, or sleep medicine. Twenty-four medical specialty boards offer certification in more than 140 specialties and subspecialties. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) comprises representatives from these 24 member boards, and its purpose is to improve the quality and safety of health care by “supporting the continuous professional development of physician specialists” [1].

Board certification is an expectation in the United States. More than 75 percent of physicians in the United States are diplomates. The other 25 percent are mainly special cases: 9 percent are physicians over the age of 60, who trained at a time when board certification was less important, and another 7 percent are physicians under 40, some of whom are probably still undergoing the board certification process [2].

The concept of specialization and creating medical specialty boards to monitor specialists most likely came about in 1908, when Derrick T. Vail, Sr., gave his presidential address to the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology [3]. He proposed that specialties should have defined sets of knowledge and that physicians should only be licensed as specialists after demonstrating the required knowledge “before an examining board” [2]. This imprimatur would permit patients to choose physicians wisely and would most likely lead to specialists’ garnering all the relevant cases in their towns; specialists would then develop greater clinical expertise and provide improved patient care. By limiting the number of specialists and creating a specialist system as described, specialists would be able to support themselves by practicing only their specialties.

Further events contributed to greater “quality control” in physicians’ provision of medical care. In 1910, Abraham Flexner’s report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching declared that higher standards were required for the people, the education, and the institutions in medical education [4]. In 1915, the National Board of Medical Examiners was founded to serve the public by providing meaningful assessments of medical students seeking to receive their medical degrees [5].

Implementing processes to safeguard the quality of physicians continued in 1917 with the establishment of the first medical specialty board, now known as the American Board of Ophthalmology. Between 1917 and 1935, the number of medical specialty boards grew to nine [6]. In 1936, the American Medical Association (AMA) set the trend for future boards by establishing the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) as an autonomous body, allowing it to prioritize patient care while being protected from the vicissitudes of politics and practice [7]. The ABIM certifies nearly 25 percent of all physicians.

Medical specialty boards are beholden to the patient. As Vail explained more than 100 years ago, board certification allows diplomates to distinguish themselves and patients to know more about their physicians [3]. The actions of medical specialty boards also improve the health of the public by decreasing the burden of disease, increasing individual productivity, and providing and more cost-effective care.

No system is perfect. Sometimes boards take steps that they later withdraw, such as in 1950, when for a period the ABA reserved the right to revoke board certification for failure to limit clinical practice to anesthesiology [8]. Sometimes boards need to take legitimate actions to which diplomates object. Two current disputes center on requirements for maintaining certification and limitations on practice.

Maintenance of Certification

In the past, physicians were board certified for life unless they violated a specific board policy, typically by committing a felony or having a medical license limited or revoked.

An important change in the last 20 or 30 years has been the development of the maintenance of certification (MOC) system, which “promotes lifelong learning and the enhancement of the clinical judgment and skills essential for high quality patient care” [9]. Time-limited certification and the need to recertify has developed over the years; for example, the American Board of Family Practice began time-limited certification in 1972, the ABIM in 1990, and the ABA in 2000 [7, 10]. When time-limited certification started, most boards required little more than obtaining continuing medical education credits and a test [7]. But with the development of MOC, requirements became more standardized across boards and continued to grow to include practice assessment (e.g., through patient or peer surveys), simulation, and activities related to patient safety and quality improvement.

The latest ABIM MOC iteration has spawned some pushback. ABIM will now report a physician is meeting MOC requirements if he or she is continuously engaged in MOC activities. Diplomates are required to complete a MOC activity every two years, acquire a certain number of points (given for activities) every five years, complete patient safety and patient voice modules every five years, and pass the MOC exam every 10 years [11]. The ABIM changed its MOC requirements because of the concern that merely “engaging in MOC” every 10 years was insufficient to keep up to date with clinical changes.

There are two main approaches that diplomates have taken in addressing concerns about changing MOC requirements: petitions and lawsuits.

Petitions. Since March 2014, more than 19,000 physicians have signed a petition requesting that the only requirement for recertification of ABIM diplomates be the decennial exam [12]. Others have suggested that some of the ABIM’s tactics, such as asking patients to consider encouraging their physicians to become board certified, constitute bullying. The petition also declared that MOC “adds significant time and expense to board certification” and that “scientific data indicating MOC provides benefit is lacking” [12].

In its response to this petition, the ABIM noted that the yearly cost for MOC was $200-$400, a fee that included access to the ABIM self-evaluation products for which physicians can earn continuing medical education credits. The annual fee also includes the cost of the first ten-year exam, which can be upwards of $1,500 in some specialties. The ABIM response estimated that its MOC requirements should take 5 to 20 hours annually to fulfill in nonexamination years and pointed out that “diplomates who complete them [MOC activities] report they are valuable” [13].

It seems that, while the ABIM is doing its best to maintain the commitment to ensure its member physicians are professional and skilled, the 19,000-plus physicians who signed the petition are tired of being subject to requirements they do not feel benefit patients. Both views have validity. The ABIM may underestimate the time and economic costs of fulfilling these requirements—remembering that the fees paid to the ABIM are only the beginning of the costs. The petitioning physicians may understate the value that ABIM’s nudges have in maintaining their knowledge and skill.

Medical knowledge and practice changes more often than once every ten years, so requiring education and practice improvements between the decennial exams hardly seems worth arguing about. But it is reasonable to expect that designated education and practice improvement activities have evidence supporting their effectiveness, to make sure that diplomates’ time is being used wisely, the goals are being achieved, and the costs of participation are not wasted [14]. In her recent New York Times op-ed article “Stop Wasting Doctors’ Time,” Danielle Ofri, MD, criticized the MOC requirements for ABIM diplomates, particularly the “practice assessments meant to improve care in your own practice that end up being just onerous” [15]. She points out that most of medical practice is like an open-book exam—and that it may make more sense to examine in a way similar to clinical practice.

Lawsuits. Another means of protest against boards’ actions is seen in the ongoing case of American Association of Physicians and Surgeons v. American Board of Medical Specialties [16]. The American Association of Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS) suit claims that fulfilling MOC standards is burdensome, expensive and time-consuming, does not benefit patients, and has ramifications for physicians who do not meet MOC requirements such as “being excluded from hospitals and insurance plans” and “being publicly disparaged by ABMS as someone who is not ‘Meeting MOC Requirements’” [16]. AAPS suggested that the ABMS is attempting to maximize revenue by requiring participation in MOC and by providing products that meet the requirements. AAPS also expressed concern that, because of MOC, patients will have less access to physicians due to both the aforementioned exclusion of some physicians from hospitals and the time spent completing MOC requirements. As of December 20, 2014, the parties are waiting on the court to rule on the ABMS motion to dismiss.

Putting aside the legitimacy of the argument, using litigation to challenge medical specialty boards’ policies typically poisons future relationships and should be used only after nonlegal negotiations have failed.

Limitations on Clinical Practice

Diplomates have also objected when boards threaten revocation of certification for diplomates who do not limit clinical practice in prescribed ways. For example, gynecologists often manage the care of men at high risk for anal cancer because of similarities between treating anal and cervical cancer. The American Board of Gynecology (ABOG), feeling that managing the care of these men was outside of its mission of treating women and that its diplomates did not have proper training for the care of men, declared that gynecologists were not permitted to provide this care for men, although there was no evidence that gynecologists providing this care were harming patients. The result could have had damaging effects on research and clinical practice [17]. A hullabaloo followed. Particularly agitated were the male patients who lost their physicians. The public and professional outcry caused the ABOG to change its stance, in part to preserve the focus on its primary mission [18].

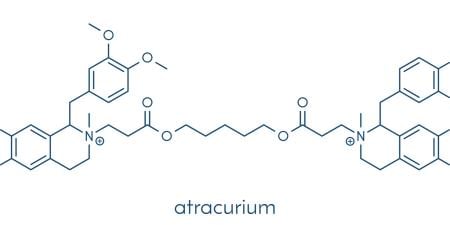

Boards have also prohibited diplomates from performing some legal actions out of concern for the specialty’s reputation with patients. In 2010, the ABA determined that participation in lethal injection, as defined and prohibited by AMA policy, was grounds for revocation of board certification [19, 20]. The ABA explained that anesthesiologists in particular should not participate in lethal injection, because lethal injection superficially mimics anesthesia, leading to patients’ distrust of their anesthesiologists. If this were true, causing this distrust would violate physicians’ obligation to put patients’ interests first. This prohibition avoided the outcry over ABOG’s action, perhaps because the number of physicians affected was much smaller.

In its role of establishing professional standards and because of the similarities between lethal injection and anesthesia practice, it may be reasonable for the ABA to prohibit diplomates from performing this action. But that raises two questions: when is it legitimate for boards to prohibit diplomates from performing legal actions, and does prohibition of one legal action set the standard that a board can prohibit members from performing other legal medical actions merely out of concern for the specialty’s reputation (that is, the fact that some people oppose the particular action on moral grounds) [21]? In that regard, this action is a sea change from modern board practice, and one that requires discussion and the development of ground rules for the revocation of board certification for legal actions.

Conclusion

Medical specialty boards contribute significantly to a successful health care system. But boards are not perfect, and they, with the best of intentions, do overreach. Once they overreach, it often sets a pattern that is hard to reverse. In general, boards seek to be inclusive, so diplomates are obligated to participate in shaping them. For diplomates deliberating about boards’ actions, considerations of whether a board action makes sense should include asking whether the goals are valid and what supports that view. For example, ensuring physician competence, because it relates to ensuring high-quality patient care, is clearly a valid goal demanded by professional ethics and state medical practice laws, while limiting gynecologists’ activities may be a valid goal, depending on the level of qualitative and quantitative evidence of harms. Similarly, safeguarding a specialty’s reputation is valid, but public discussion and sufficient evidence of harm should precede the prohibition of a legal action. Another consideration is whether there is evidence to indicate that the intervention will achieve relevant goals. Continuing medical education in all competencies is likely to improve patient care, but, given the time and opportunity costs of fulfilling MOC requirements, better data need to be used to determine which activities are most relevant.

Despite these hiccups, boards do a vital function well. New physicians who enter the system and get disenchanted (and they will get disenchanted) must remember that the driving force behind medical specialty boards is to meet the needs of the public.

References

-

American Board of Medical Specialties. Better patient care is built on higher standards. http://www.abms.org/about-abms/. Accessed January 20, 2015.

-

Young A, Chaudhry HJ, Thomas JV, Dugan MA. A census of actively licensed physicians in the United States. J Med Ed. 2013;99:11-24.

-

Vail DT. The limitations of ophthalmic practice. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1908;13:1-6.

-

Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. New York, NY: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

-

National Board of Medical Examiners. About the NBME. http://www.nbme.org/about/. Accessed January 20, 2015.

-

American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS member boards. http://www.abms.org/about-abms/member-boards/. Accessed January 30, 2015.

-

Cassel CK, Holmboe ES. Professionalism and accountability: the role of specialty board certification. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2008;119:295-304.

-

American Board of Anesthesiology. Booklet of Information. New York, NY: American Board of Anesthesiology; 1950:6-7.

-

American Board of Internal Medicine. Maintenance of certification guide. http://www.abim.org/maintenance-of-certification/. Accessed December 20, 2014.

-

American Board of Anesthesiology. Maintenance of certification in anesthesiology (MOCA). http://www.theaba.org/Home/anesthesiology_maintenance. Accessed January 30, 2015.

-

American Board of Internal Medicine. What changed in 2014? http://www.abim.org/maintenance-of-certification/faq-2014-program-changes/what-changed-in-2014.aspx. Accessed December 20, 2014.

-

ABIM should recall the recent changes to maintenance of certification (MOC). http://www.petitionbuzz.com/petitions/recallmoc. Opened March 10, 2014. Accessed December 20, 2014.

-

Statement from Richard J. Baron, MD, MACP, president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine regarding anti-MOC petition [news release]. Philadelphia, PA: American Board of Internal Medicine; April 28, 2014. http://www.abim.org/news/statement-from-richard-baron-regarding-anti-moc-petition.aspx. Accessed December 20, 2014.

-

American Board of Internal Medicine. Requirements. http://www.abim.org/maintenance-of-certification/requirements.aspx. Accessed December 20, 2014.

-

Ofri D. Stop wasting doctors’ time: board-certification has gone too far. New York Times. December 15, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/16/opinion/board-certification-has-gone-too-far.html?_r=0. Accessed January 20, 2015.

-

Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, Inc. v American Board of Medical Specialties, No. 1:14-CV-2705 (NDIL).

-

Grady D. Gynecologists run afoul of panel when patient is male. New York Times. November 22, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/23/health/gynecologists-run-afoul-of-panel-when-patient-is-male.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed January 20, 2015.

-

Johnson, EM. US board allows gynecologists to treat more men. Reuters. January 31, 2014. http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/01/31/us-usa-gynecology-idUSBREA0U0RW20140131. Accessed December 20, 2014.

-

American Board of Anesthesiology. Anesthesiologists and capital punishment. ABA News. 2010; 23(1):9-10.

-

American Medical Association. Opinion 2.06 Capital punishment. Code of Medical Ethics. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion206.page. Accessed December 20, 2014.

- Waisel DB. Revocation of board certification for legally permitted activities. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(7):869-872.