Pathology, as a medical specialty, deals with the interpretation of changes in human tissues that cause or are caused by disease. Pathologists render diagnoses from laboratory analyses of varied specimens such as blood, urine, and other body fluids as well as microscopic examination of solid tissue from biopsies or surgical resections. In addition to diagnosis, pathologists determine cause and effect of death and disease through autopsy and techniques of molecular pathology. Pathologists are thus laboratory-based physicians. In medicine, they are sometimes stereotyped as basement dwellers, removed from direct patient contact, working with only the dead and inert. On this stereotype of pathologists as sheltered in their subterranean quarters, issues of medical ethics might seem a distant consideration.

There are good reasons, however, to carefully consider pathology ethics. A survey of American pathology department chairs across the United States found that 94 percent believed ethical issues were faced by pathologists either occasionally or frequently [1]. Commonly encountered ethical scenarios involved use of tissues for research, professionalism, and confidentiality or privacy [1]. Additionally, “84 percent of [representatives of residency] programs believed that ethical issues were underrecognized, and 38 percent believed that current ethics training was inadequate” [2], although 62 percent reported offering formal ethics instruction in residency training programs. A more recent international survey of ethics training in laboratory medicine found that even fewer programs offered formal training in ethics: roughly a third of surveyed programs offered formal training in medical ethics and roughly a quarter offered formal training in professional ethics [3]. Clearly, there is a need for better training in pathology ethics and more resources to address the often unique ethical scenarios encountered by pathologists in medicine.

A goal of this issue of the AMA Journal of Ethics® is to bring to light some of the ethical complexities faced by pathologists in their daily practice. The five cases presented here explore a few common scenarios and offer practical guidance for navigating them. In their commentary on a case of consent for autopsy, Megan Lane and Christian J. Vercler argue that a sociocultural—but not a Cartesian—perspective on the postmortem body necessitates informed consent and discuss how to approach a family about consent when the autopsy’s purpose is to investigate possible surgical error. Two cases look at professional interactions between the pathologist and clinician. In their commentary on a case involving preferential treatment of a VIP patient, Virginia Sheffield and Lauren B. Smith examine possible harms of this practice and institutional factors contributing to it. Martin J. Magers and Sandro K. Cinti respond to a case of a clinician’s request for additional tissue stains that are not indicated by recommending that pathologists not put professional relationships before the patient’s best interest. Although direct patient interaction is limited in pathology, cytopathologists can be directly involved with patient care when they perform fine needle aspirations at a patient’s bedside. Michael H. Roh and Andrew G. Shuman discuss an obligation to disclose—and barriers to disclosure—in a case involving a patient’s request for disclosure of a preliminary diagnosis that would be “bad news.” The final case examines ethical obligations of pathologists in their roles as laboratory managers. John P. Sherbeck and Renee D. Boss examine the conflict between the ethical principles of beneficence and social justice in a case involving a decision about platelet transfusion for a palliative care patient.

A central theme in this issue is communication—between physicians; among physicians, patients, and patients’ loved ones; and even virtually, through social media. Two articles examine improving professional communication and obstacles to transparency. Suzanne Dintzis describes a course for pathology residents that she and her colleagues at the University of Washington developed to cultivate best practice procedures for effective communication. And Ifeoma U. Perkins reviews the literature on and discusses four barriers to pathologists’ disclosure of medical errors.

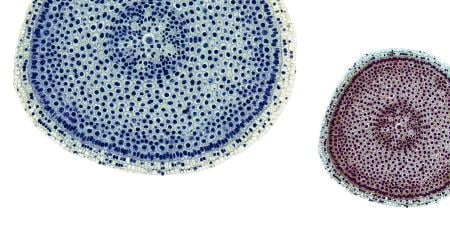

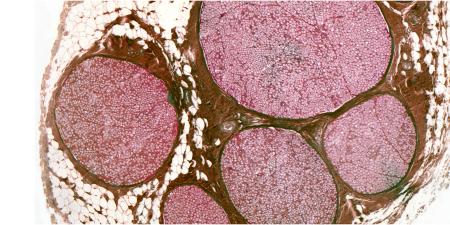

New technologies that enable rapid sharing of information generate ethical questions, both familiar and novel. The visual and aesthetic nature of pathology makes it especially easy to use social media platforms, such as Twitter and Instagram, to share images and information, but doing so raises concerns about potential privacy violations. But as Genevieve M. Crane and Jerad M. Gardner argue, social media posts should be governed by the same ethical standards as images published in a case report, and the authors present ethical and practical guidelines for pathologists who use social media professionally. New ethical concerns have also arisen with the evolution of direct-to-patient laboratory test reporting, which enables patients to access lab results without physician interpretation. Kristina A. Davis and Lauren B. Smith evaluate some of the risks and benefits of the ease with which patients can access basic laboratory information and specialized pathology reports through online patient portals.

Observation is another central theme of this issue. William E. Stempsey develops Foucault’s concept of “the gaze” to explore differences between pathologists’ and families’ perceptions of autopsy with a view to improving informed consent, which, in turn, should lead to more—and more carefully considered—autopsies. And Katrina A. Bramstedt discusses the training in visual arts afforded by Bond University’s medical humanities program and students’ positive assessment of the curriculum.

Finally, in this issue’s podcast, Theonia Boyd discusses clinical and ethical reasons for completing an autopsy as well as a few of the ethical issues faced by pathologists in their role as medical expert witness.

The advent of new technologies and the rise of molecular pathology promise to bring even more complex ethical questions to the fore. The selection of case commentaries and articles in this issue of the AMA Journal of Ethics gets us thinking about ethical issues by addressing a few neglected ethical questions that are nonetheless common in pathology and laboratory medicine.

References

- Domen RE. Ethical and professional issues in pathology: a survey of current issues and educational efforts. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(8):779-782.

-

Domen, 779.

-

Bruns DE, Burtis CA, Gronowski AM; IFCC Task Force on Ethics. Variability of ethics education in laboratory medicine training programs: results of an international survey. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;442:115-118.