Abstract

Promoting awareness of human trafficking by sharing trauma survivors’ art and summaries of their life stories suggests ethical complexities that have been typically neglected by bioethicists. Although these survivors voluntarily share the objects they created during art therapy sessions, they are still at risk of harm, including further exploitation, due to their vulnerability, high rates of victim sensitivity, and the mental health consequences of their traumatic experiences. While some argue that the benefits of sublimation and art therapy for human trafficking survivors make sharing their art worth the risk, anti-trafficking organizations and supporters of such art exhibitions have responsibilities to be trauma informed.

Because you have listened to my story I can let go of my demons.

Murasaki Shikibu [1]

Introduction

Psychologists and others working with trafficked persons use art therapy to facilitate nonverbal expression of the trauma experience, which may decrease avoidance of emotion [2]. Art was first considered therapeutic after psychologists observed drawings created by the mentally ill. The use and recognition of art along with typical psychotherapeutic interventions increased in the 1930s [3]. It wasn’t until the 1990s, however, that art therapy became applied specifically to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including the treatment of survivors of human trafficking [3]. Art therapy, used as an alternative or supplemental therapy, shows promise in amelioration of posttraumatic stress and traumatic memories through stimulating the patient’s senses, thereby facilitating revelation and self-discovery [3]. Lidia Gorceag, a psychologist in Moldova who uses art therapy in treating trafficking survivors, describes art therapy as “a very good exercise. A life road. The woman reproduces the most important events she has been through in the images. She usually draws some symbols, and these images serve as benchmarks for further therapy sessions” [4].

Artwork created by human trafficking survivors during art therapy treatment for PTSD is being used by a small number of advocacy groups to promote awareness of human trafficking. Artists donate their works and receive no financial remuneration. For example, the Awakenings Foundation Center, an organization dedicated to showcasing the artistic works of survivors of sexual violence, sponsored an exhibition in Chicago titled “The Art of Healing” during National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month in January 2016 [5]. This exhibition was free to visitors. Another organization, the Hope and Liberation Coalition (HLC), also presents traveling exhibitions of art therapy creations by human trafficking survivors throughout the year [6]. This group of Ohio art centers, artists, trafficking survivors, and others raises awareness and sells tickets to the events, giving the proceeds to anti-human trafficking programs. Well-known groups such as Save the Children and Human Rights Watch have also used art exhibits, such as the one by survivors of the war in Darfur, to raise awareness of human rights abuses [7, 8].

Such exhibits raise ethical questions about whether trafficking survivors are unintentionally being exploited by anti-trafficking advocates. In this essay, I examine the possible harms to trafficking survivors of displaying their therapeutic artwork, how such harms can be prevented, and the potential benefits of art therapy.

Art Exhibition as a Source of Harm?

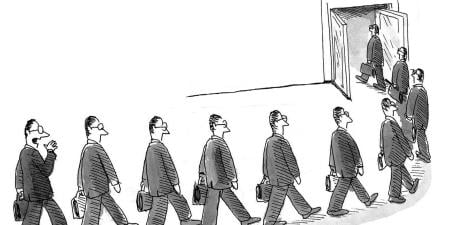

Some groups that use human trafficking survivors’ artwork and stories to promote awareness have been accused of taking advantage of these survivors, attracting interest by drawing explicitly upon survivors’ painful experiences. For example, the journalist Scott Downman reported that an MTV documentary featuring trafficked children in Cambodia stereotyped and stigmatized the trafficked children and sensationalized the issue [9]. In instances like these, viewers are encouraged to see the survivors as stereotyped victims. Instead of sympathy and moral outrage moving the viewer to action, the viewer indulges dark pleasures. Images of people in pain, including emotional distress, humiliation, and even mild embarrassment, give viewers “a particular kind of pleasure, a glimpse at the disordered, frightening, repellent side of life” [10], an experience of schadenfreude. Gina Howard, for example, an advocate with HLC, states that due to the tendency of some media outlets to reduce human trafficking survivors’ complex and varied stories to sound bites, her organization “partners with media sources known for their compassionate, informed portrayal of trafficking survivors. Otherwise, trafficking survivors are less likely to be viewed as actual people with hopes, dreams and talents, and far more likely to be reduced to compilations of the abuses and violence inflicted upon them” (written communication, August 2016). Increased public stigma about trafficking survivors leads to reduction in quality of life through low self-esteem, unemployment, poorer health outcomes, and reduced well-being [11].

Other art installations have been accused of ethically problematic and possibly exploitative actions, though in different ways. Artist Guillermo Varga starved a dog to death in an art installation to protest a drug addict’s murder by two guard dogs. This instigated the creation of other exhibitions by artists who also utilized shocking animal cruelty and death as “art” [12]. Photographer Jonathan Hobin used children to re-enact controversial or tragic events, such those that happened on September 11, 2001 and the death of Diana, Princess of Wales [13]. In these instances, the artists gained notoriety for utilizing subjects who experienced negative side effects and lacked control over their participation. Although trafficking survivors might seem to be making decisions of their own volition, they adapted and survived trafficking by allowing themselves to be dominated and manipulated. Unintentionally making decisions for trafficking survivors—which undermines their autonomy—can erode trust, result in “choices” made against their will, and increase trauma [14]. Justice requires equalization of power, which, in this case, can be gained through the survivors’ increased control over the display of their art and access to their story, thus preventing exploitation.

Trauma-informed training ensures that advocates understand the difference between autonomy and exploitation. Trauma-informed care (TIC) provides services in a welcoming and appropriate manner with an understanding of the biopsychosocial effects of trauma and minimizes re-traumatization [15]. “If you’re not informed about trauma, you can easily re-exploit someone. I believe strongly if you’re going to work in the anti-trafficking movement, you have an obligation to become trained in trauma-informed care,” says Margeaux Gray, a survivor and artist (oral communication, July 2016). According to Gray, this obligation extends to those working in any arena where violence occurs, such as intimate partner violence.

What these examples suggest is the ethical and clinical importance of considering how good intentions of organizations seeking to raise awareness about human trafficking actually play out for those whose work and traumatic experiences are on display for that purpose. Whether the artist experiences more harm or benefit from a survivor-focused art exhibit is the direct result of purposeful or incidental actions of the advocates working with them as well as the response of the viewing public.

Preventing Harm to Trafficking Survivor Artists

According to one study, women survivors of human trafficking develop significant rates of mental illness, with 35.8 percent suffering from PTSD with or without other disorders, 12.5 percent having depression without PTSD, and 5.8 percent having another anxiety disorder [16]. Male survivors suffer the same problems in smaller numbers [17]. The loss of choice that is fundamental to trafficking leads to a loss of sense of self [18]. This loss of self in turn leads to an inability to relate to the world, identify the source of pain and, in the end, heal. Beth Gherardi, the art therapist associated with HLC, explains, “Stripped of our humanity, our entire nervous system and ability to hold reality are compromised. The chaos and pain of this unraveling, this loosening and splintering of one’s sense of self and perception of the world, is at the core of trauma” (written communication, September 2016). Making choices enables survivors to gradually regain their realization of power and of self. Common across publications and areas of practice is the idea that restoring choice is critical for survivor recovery [15]. Art therapists and exhibitors should thus work closely with survivor-artists to foster their sense of agency and control over their work. “Giving survivors options and choices and not be[ing] constrained in a box,” is important, says Gray because “it lessens the chances of the survivor being re-exploited. Instead it gives the survivor an opportunity to be empowered and can assist them in their healing process” (oral communication, July 2016). She suggests that art installations give the artists as many choices as possible, even if it’s only the placement of the artwork on the wall or what position the art should be displayed in.

Many survivors of abuse also have “victim sensitivity.” People with victim sensitivity are sensitive to perceiving cues of untrustworthiness, even if the chance is small of a situation being exploitative, making them less likely to trust others and more likely to have suspicious thoughts and behave uncooperatively [19]. This can interfere with survivors’ capacities to explore relationships with others, because the result of their reactions reinforces their negative expectations about others. People with victim sensitivity are also more likely to associate ambiguous social situations with injustice, and victim sensitivity is the strongest predictor of aggressive behavior [19]. Thus even groups that mean well can hurt the survivors’ healing process if a perceived break in trust occurs. To promote trust, anti-trafficking organizations exhibiting survivors’ artwork should encourage collaboration among survivors. Says Lyndsey Remarque, an artist, about Hope and Liberation Coalition, “Our group is run by artists, so we have all the control of the projects we do and where we exhibit” (written communication, August 2016).

Organizations seeking to promote awareness about human trafficking should bear in mind that people who have been traumatized by a relative or someone close to them are more vulnerable to adverse outcomes than those who lack close connections to the perpetrator of the traumatic experience [20]. Moreover, betrayal trauma—“when the people or institutions on which a person depends for survival significantly violate that person’s trust or well-being” [20]—leads to more intense symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety [20].

The Healing Power of Art for Trafficking Survivors

The art created by trafficking survivors and displayed in anti-trafficking exhibits facilitates artists’ healing processes. A recent systematic review weakly supports art therapy for trauma, largely due to a lack of research [21], but creative art therapies are recommended by the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies [2]. Neurobiological theories propose that trauma interrupts communication between the verbal left hemisphere and the nonverbal right hemisphere and that, during recovery, the two hemispheres still have diminished communication [22]. This leads to alexithymia, the inability to identify and describe emotions. Art therapy helps survivors reassociate experiences with words by facilitating a survivor’s focus on creating visual representations (drawings, paintings, or sculpture, for example) about their experiences of trauma [22]. Gherardi explains, “For trafficking survivors, images and art making can speak for this place in them that is beyond words” (written communication, September 2016). Art therapy allows the right brain to produce a visual representation, then the left brain can state what is represented, allowing for what Gantt and Tinnin describe as “narrative closure, making the traumatic events past tense, imbuing nonverbal material with verbal description, and re-contextualizing fragmented experience” [23]. Proponents of this theory argue that this partnership between the left and right hemispheres is inherent in the process of making art and that art therapy recreates the partnership between the traumatized “emotional” brain and the “rational brain” [22]. Gray explains, “Sometimes it’s hard to understand what I’m trying to say or an emotion I’m trying to put a name to, but it comes through in my art. It gives myself and others an opportunity to understand it from a different perspective” (oral communication, July 2016).

Creating art is also a way for survivors to feel that they matter as individuals. “During my trafficking it was a way to be heard,” says Gray, “because I knew that saying anything was unacceptable, but when I created art, I heard my voice” (oral communication, July 2016). For survivors, art can help in the process of defining themselves and recovering a sense of agency. “Art takes on an experiential role of helping survivors/children become themselves instead of being someone else. This understanding and appreciation of ‘who you are’ is essential to overcoming one’s problems,” says one youth outreach instructor who goes by the name “Art Lady” (written communication, August 2016). Enslavement and trafficking strip away victims’ sense of identity and objectifies them; art therapy allows some of the survivors to rediscover a sense of self on their own terms.

Art therapy can also be done with several survivors, as a group session. Ellie Gardner, a psychology student and advocate working with Hope and Liberation Coalition, states, “If you do art with others, you create a deep bond, which is over and over again something survivors state they need. If you display art, you are vulnerable, but … a powerful voice to tell your story … is the pinnacle of becoming strong in [human trafficking] survival” (written communication, August 2016).

Some survivors who display their art publicly say that exhibiting their work has hastened their recovery. Gray says that knowing that her art touches people “makes a significant difference in my life” (oral communication, July 2016). Remarque, who displays at anti-trafficking exhibitions, states, “During our events we don’t look to change the world, but we look to change the minds of the people in it. Art is a way to open a dialogue in people that sometimes they didn’t know they had in them” (written communication, August 2016). By presenting their art in a public forum, receiving positive recognition from the community, and seeing anti-trafficking changes in the public environment, trafficking survivors receive a benefit in addition to the healing they received through the art therapy itself.

Art Therapy as a Strategy for Bringing Sublimated Emotions to Conscious Levels of Awareness

Freud described sublimation, a psychological defense mechanism, as the ideal objective of any successful therapy, and sublimation can help explain the benefit of exhibiting one’s art work [24]. In sublimation, unacceptable desires, feelings, or thoughts are transferred to a new activity that is not only less anxiety-provoking but also, perhaps, praised and valued by society [24]. Human trafficking survivors sometimes are so traumatized they cannot articulate their experiences to find healing, but “art therapy gives them a way to tell their stories without using language, instead using painting, drawing and poetry to develop a narrative about what has happened to them” [25]. One survivor, through multiple art therapy sessions, was empowered to tell her story through describing her art, stating, “This is an image symbolizing my unhappiness and sorrow at being trafficked and sold into prostitution” [26]. This conscious expression of experience previously not articulable is the ultimate goal of therapy. Art therapy has additional benefits, such as increasing resilience and anxiety management skills and realizing testimony and destigmatization [2].

There is a risk of criticism, but I believe those who attend these exhibitions of survivors’ artwork are almost exclusively supporters who see the value in the strength shown by these artists. An example of possible sublimation of anger and other complex emotions is provided by Patty Wetterling, whose son was kidnapped in 1989 at the age of 11 by a sexual predator. She became a child safety advocate, and in 1994 Congress passed a law named after her son to establish sex offender registries [27].

Conclusion

To minimize risk of harm, including exploitation, to human trafficking survivors, I believe organizations should develop written protocols and make them available for use by anti-trafficking groups as the anti-trafficking movement grows. Large anti-trafficking organizations, in particular, should consider addressing guidelines for individual advocates or organizations to use. A main theme of these protocols should be giving survivor-artists choices about when and how to exhibit their work and allowing them to decide how much they participate. These protocols should also require training for all staff and advocates who interact with survivors about the nature and effects of current and lifetime trauma [15].

The fight against human trafficking needs advocates, and encouraging survivors to participate in a way that nurtures their healing could allow the movement to attract more survivors and partners. As Howard notes, “It is essential that … ‘we’—the public, charitable organizations and media sources—do not further add to the reduction of the spirits and dignity of trafficking survivors who have already been exploited and reduced to mere commodities by traffickers” (written communication, August 2016).

References

-

Shikabu M. The Tale of Geni. Quoted by: Atkinson R. The Life Story Interview: Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;1998:65.

-

Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010.

-

Malchiodi CA. Expressive therapies: history, theory, and practice. In: Malchiodi CA. Expressive Therapies. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005:1-15.

-

Botnaru V, Barbarosie L. Helping victims of sexual trafficking find the courage to recover. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. http://www.rferl.org/a/Moldovan_Psychologist_Helps_Victims_of_Sexual_Trafficking_Find_Courage_To_Recover/1197143.html. Published September 8, 2008. Accessed October 9, 2016.

-

Cook County Human Trafficking Task Force. The Art of Healing—an event to raise awareness for national slavery and human trafficking prevention month. http://www.cookcountytaskforce.org/events/the-art-of-healing-an-event-to-raise-awareness-for-national-slavery-and-human-trafficking-prevention-month. Published December 17, 2015. Accessed September 25, 2016.

-

Hope and Liberation Coalition. Exhibits. https://hopeandliberationcoalition.com/exhibits/. Accessed September 25, 2016.

-

McEachran R. Art in the aftermath: healing the victims of trafficking and slavery. Guardian. February 26, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2014/feb/26/art-therapy-trafficking-slavery. Accessed September 9, 2016.

-

Human Rights Watch. Darfur drawn: conflict in Darfur through children’s eyes. https://www.hrw.org/legacy/photos/2005/darfur/drawings/introduction.htm. Accessed November 18, 2016.

-

Downman S. Victims of atrocities or victims of the media—rethinking media coverage of human rights abuses. Paper presented at: Journalism Association Education of Australia Conference; November 28-30, 2011; Adelaide, Australia. https://newspaperjan.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/jeaa-2011-report4.docx. Accessed November 11, 2016.

-

Kennicott P. What are we losing in the Web’s images of suffering and schadenfreude? Washington Post. December 27, 2012. https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/what-are-we-losing-in-the-webs-images-of-suffering-and-schadenfreude/2012/12/27/6e61aa20-4df2-11e2-950a-7863a013264b_story.html. Accessed October 9, 2016.

-

Egbe CO. Experiences and effects of psychiatric stigma: monologues of the stigmatizers and the stigmatized in an African setting. Int J Qual Health Stud Well-being. 2015;10:27954. http://www.ijqhw.net/index.php/qhw/article/view/27954. Accessed November 18, 2016.

-

Wayner R. The exploitation of animals in modern conceptual art. Encyclopedia Britannica. http://advocacy.britannica.com/blog/advocacy/2010/11/the-exploitation-of-animals-in-modern-conceptual-art. Published November 22, 2010. Accessed September 5, 2016.

-

Jonathan Hobin re-creates the world’s most infamous tragedies with children. Vice. April 29, 2013. http://www.vice.com/read/jonathan-hobin-recreates-the-worlds-most-infamous-tragedies-with-children. Accessed September 7, 2013.

-

Family Violence Prevention Fund. Collaborating to help trafficking survivors: emerging issues and practice pointers. https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/userfiles/file/ImmigrantWomen/Collaborating%20to%20Help%20Trafficking%20Survivors%20Final.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Wilson JM, Fauci JE, Goodman LA. Bringing trauma-informed practice to domestic violence programs: a qualitative analysis of current approaches. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85(6):586-599.

-

Abas M, Ostrovschi NV, Prince M, Gorceag VI, Trigub C, Oram S. Risk factors for mental disorders in women survivors of human trafficking: a historical cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:204. https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-13-204. Accessed November 18, 2016.

- Oram S, Abas M, Bick D, Boyle A, French R, Jakobowitz S. Human trafficking and health: a survey of male and female survivors in England. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(6):1073-1078.

- Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn. 1983;5(2):168-195.

-

Gollwitzer M, Süssenbach P, Hannuschke M. Victimization experiences and the stabilization of victim sensitivity. Front Psychol. 2015;6:439. http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00439/full. Accessed November 18, 2016.

-

Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma. In: Reyes G, Elhai JD, Ford JD, eds. The Encyclopedia of Psychological Trauma. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2008:76.

- Schouten KA, de Niet GJ, Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ, Hutschemaekers GJ. The effectiveness of art therapy in the treatment of traumatized adults: a systematic review on art therapy and trauma. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16(2):220-228.

- Gantt L, Tinnin LW. Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. Arts Psychother. 2009;36(3):148-153.

-

Gantt, Tinnin, 152.

- Kim E, Zeppenfeld V, Cohen D. Sublimation, culture, and creativity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;105(4):639-666.

-

The road less traveled: Atira Tan. LETSGLO. April 5, 2014. http://blog.letsglo.com/the-road-less-travelled-atira-tan/. Accessed November 16, 2016.

-

Survivor’s stories. Art2Healing Project. http://www.theart2healingproject.org/survivorStory.htm. Accessed November 16, 2016.

-

Bleyer J. Patty Wetterling questions sex offender laws. City Pages. March 20, 2013. http://www.citypages.com/news/patty-wetterling-questions-sex-offender-laws-6766534. Accessed November 18, 2016.