Abstract

I advocate using graphic medicine in introductory medical ethics courses to help trainees learn about patients’ experiences of autonomy. Graphic narratives about this content offer trainees opportunities to gain insights into making diagnoses and recommending treatments. Graphic medicine can also illuminate aspects of patients’ experiences of autonomy differently than other genres. Specifically, comics allow readers to consider visual and text-based representations of a patient’s actions, speech, thoughts, and emotions. Here, I use Ellen Forney’s Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me: A Graphic Memoir and Peter Dunlap-Shohl’s My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s as two examples that can serve as pedagogical resources.

Introduction

Graphic medicine, or the use of comics in health care education and patient care, provides patients and clinicians new ways to experience and understand health, illness, and care [1, 2] through visual representations of experiences such as pain, fear, and self-reflection [3, 4]. Usually students are familiar with comics, which make them convenient to introduce as a learning tool [5-7]. The medium lends itself to presentation: pages and single frames from comics are manageable as objects of analysis within a classroom context [1, 3, 4, 8]. Often, what might require complex prose or film is well represented by a single comic frame or page. To depict the complexity of experience, graphic creators often use emanata, text or icons that represent thoughts or feelings. Combinations of words and illustrations allow graphic creators to communicate feelings more richly than through visuals or text alone. Comics thus provide students a medium to witness quickly moving thoughts and feelings and also to discern individual action, speech, feelings, and thoughts [1, 3, 9].

Using comics, students can also grasp ethical concepts and problems that are difficult to understand, such as the complex effects of health care on patients’ experience of autonomy. In this paper, I advocate using comics to assist teaching about patient experiences related to autonomy because graphic medicine is a medium that uniquely captures dimensions of crisis and deliberation associated with health care.

Using Comics to Teach about Patient Autonomy

Respect for autonomy is a principle of medicine that refers to respect for the patient’s ability to self-govern without “controlling interference by others and … limitations, such as inadequate understanding” [10]. Relational autonomydescribes the intersubjective and social dimensions of autonomy [11]. Patients experience varying degrees of autonomy within health care contexts that might affect their self-trust and self-evaluation [12]. Moreover, abilities and opportunities to be autonomous are affected by numerous factors, including health literacy, social support systems, inequities, and clinician communication skills [13, 14]. Because turmoil and tension experienced by patients can undermine their abilities to convey their experiences, trainees might be unaware of how patient autonomy is affected by illness, diagnosis, treatment, and clinician communication [15-17]. In what follows, I discuss two examples of graphic medicine that can serve as pedagogical resources for increasing students’ understanding of patient autonomy, especially as it relates to diagnosis and treatment.

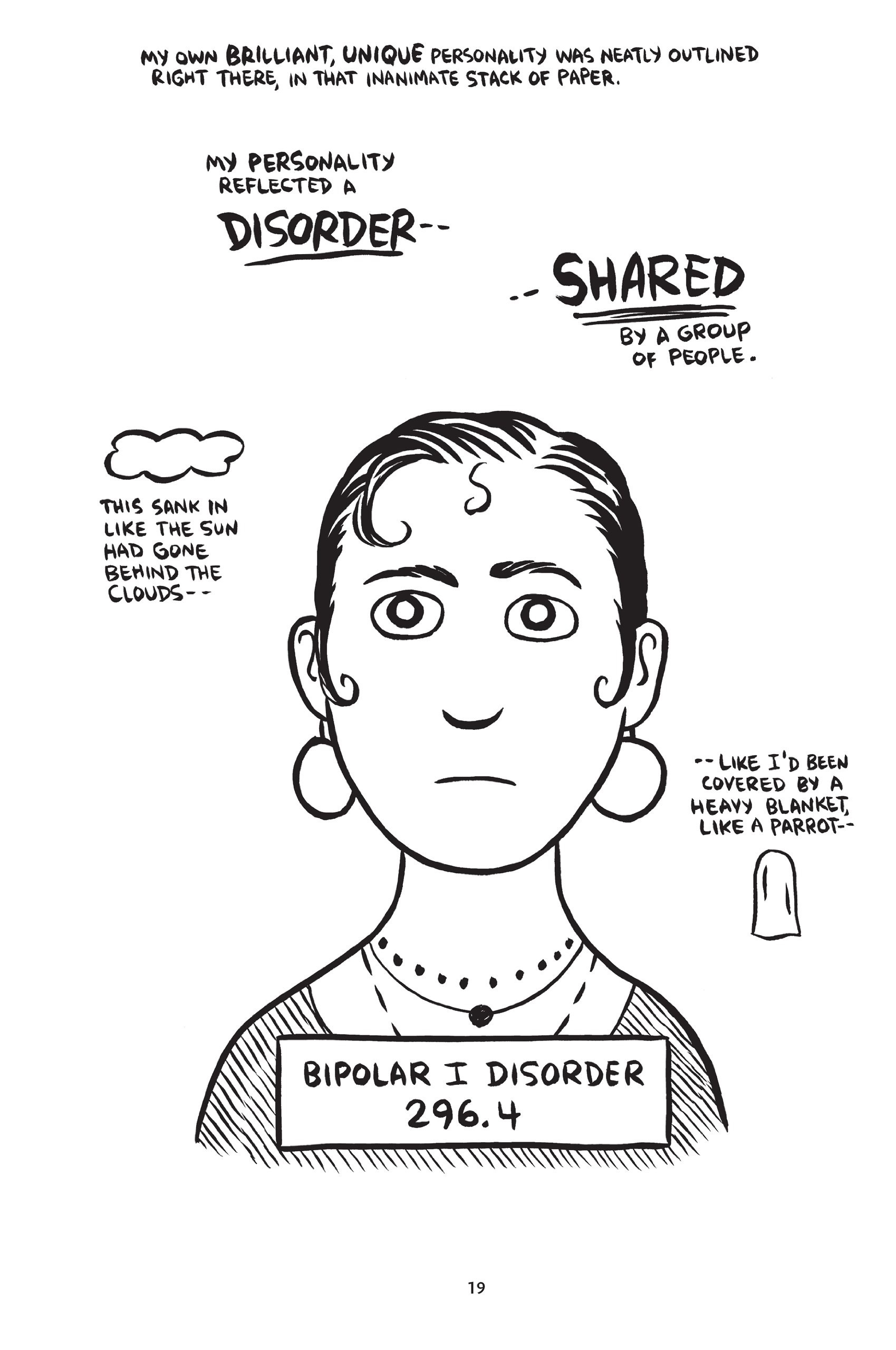

Marbles. Ellen Forney’s graphic memoir Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me: A Graphic Memoir is ideal for teaching students about a patient’s experience of autonomy following diagnosis and during treatment for bipolar 1 mood disorder [18]. Forney begins with her experience of a manic episode and the therapeutic sessions that follow. She illustrates not only the exchange of dialogue in therapeutic encounters but also the thoughts and images that occur to her during the sessions. For example, she illustrates her second meeting with the psychiatrist, taking the reader through her experience of the symptoms of bipolar 1 mood disorder as listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [19]. This scene familiarizes students with symptom-based medicine as it relates to the patient’s experience of self and autonomy. Forney’s experience of being diagnosed provides a glimpse into the moment of diagnosis and prompts questions about how it affects her sense of autonomy and agency (see figure 1). Over her torso is a text box, like those in mug shots, stating, “Bipolar I Disorder 296.4” [20]. As she states above the picture that resembles a mug shot, “My own brilliant, unique personality was neatly outlined right there, in that inanimate stack of paper. My personalityreflected a disorder—shared by a group of people” (emphasis added). On one side of her face in the picture is a cloud, below which is written, “This sank in like the sun had gone behind the clouds.” On the opposite side and lower is written, “like I’d been covered by a heavy blanket, like a parrot,” below which is a draped blanket. Her identity is represented as overtaken by the diagnosis hanging around her neck.

Figure 1. Graphic novel excerpt from Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me: A Graphic Memoir by Ellen Forney

Copyright © 2012 by Ellen Forney. Used by permission of Gotham Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

By using emanata and images that spill over one another, Forney communicates to the reader aspects of mania as she experiences them. When she experiences depressive episodes, Forney uses isolated imagery that communicates her loneliness and hopelessness. Surrounded by her narrative, a single sketch of her maligned body twisted around itself in a bird’s nest summarizes feelings of struggle that she could not convey otherwise. This is evident when she states, “I soon learned to keep drawing until I really nailed my feelings down. I didn’t get nearly the same relief if I only came close” [21]. The image conveys her feelings of isolation and helplessness, providing readers with a stark representation of her lack of autonomy caused by depression.

Comics also give Forney the ability to convey how medication threatens her autonomy. The persistent trials with different medications constantly threaten her autonomy: from her ability to control and maintain her desired weight to her self-confidence concerning her treatment decisions. One means by which she attempts to retain her autonomy is by smoking marijuana, despite her therapist’s warnings. By withholding her marijuana use from her therapist, Forney struggles to retain a sense of self that is solely her own, apart from relations with others. Readers can witness her thought processes and emotions concerning her diagnosis, her treatment, her sense of identity, and her therapist, who often takes a detached approach to Forney.

In Marbles, Forney presents clean, concise, and powerful images, dialogue, and thoughts to portray the complex effects that illness, diagnosis, and treatment had on her autonomy. Comic images like those depicted in Marbles can provide common reference points in lectures and discussions to facilitate students’ understanding of patients’ experience of threats to their autonomy and fears associated with their illness. In Marbles, readers can also gain access to the typically private realm of a patient’s deliberation, as Forney continually struggles with what to divulge to her therapist and what to retain as solely hers. Graphic narratives such as Marbles thus can assist in developing students’ caregiving skills and their responsibility to engage with patients’ emotional experiences. By depicting her emotional experiences regarding therapy sessions, Forney illuminates the importance of the patient-clinician relationship to her struggle with illness and to her sense of autonomy.

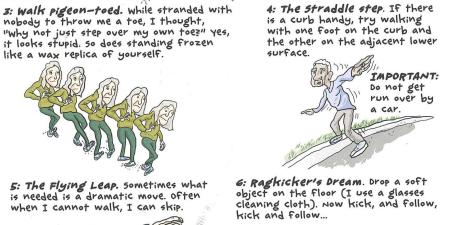

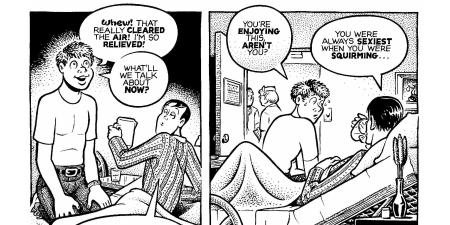

My Degeneration. Peter Dunlap-Shohl’s My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s presents another depiction of a patient’s experience of autonomy [22]. Dunlap-Shohl is an editorial cartoonist whose abilities, including those required for work, were threatened by Parkinson’s. Comics provide Dunlap-Shohl with a means to communicate his experience of illness that other media cannot convey. For instance, he personifies Parkinson’s as a man subtly diminishing his ability to self-govern [23] with whom he boxes to regain self-governance [24]. By using motion lines and emanata, he expresses the struggle of contending with the changes Parkinson’s and medication brought to his career and sense of self. In a series of illustrations, he depicts the symptoms, such as logorrhea (repetitious and often incoherent speech) and festination (an alteration in gait pattern that is marked by quick and shortened steps), which compel him to act in specific ways that betray his inability to self-govern [25]. He also illustrates his positive experiences with exercise, family, and community, which help students understand autonomy as relational. Through his vibrant characterizations of his experience, Dunlap-Shohl provides students with a unique view of how his symptoms and social supports relate to his feelings of diminishing and increasing autonomy, respectively.

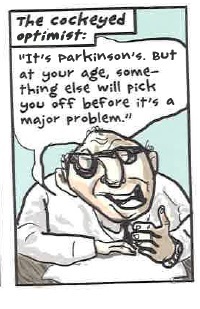

Figure 2. Dunlap-Shohl, Peter, “The cockeyed optimist,” page 8, from My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s, 2015

Copyright © 2015 by The Pennsylvania State University Press. Reprinted by Permission of The Pennsylvania State University Press.

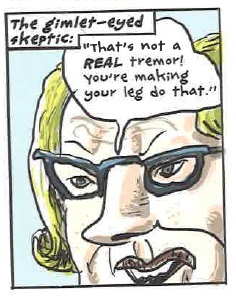

Figure 3. Dunlap-Shohl, Peter, “The gimlet-eyed skeptic,” page 8, from My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s, 2015

Copyright © 2015 by The Pennsylvania State University Press. Reprinted by permission of The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Dunlap-Shohl also illustrates his experiences of how physicians diagnose and treat Parkinson’s. Included are depictions of how different physicians deliver a diagnosis, such as “the cockeyed optimist” (see figure 2) and “the gimlet-eyed skeptic” (see figure 3), all of whom affect their patients differently [26]. In these figures, Dunlap-Shohl comments on how the delivery of a diagnosis can support or undermine a patient’s autonomy and contributes to each patient’s experience of illness, and in other frames he suggests what physicians should do to deliver a diagnosis in a way that expresses respect for a patient’s autonomy [27]. He also depicts his struggles that were the result of unsympathetic treatment and his successes that were due, in part, to care delivered with empathy and patience. An example of the latter is his experience with a movement disorder specialist on what he refers to as the “Island of the Caring and Competent,” which is the world of empathetic people who work with patients to improve the present and future [28]. Through illustration, he communicates the autonomy he achieved through exercise, family support, physicians, peers, and technology. Witnessing these experiences through comic form provides students with a lesson that diagnosis and treatment should be delivered in a manner that acknowledges patients’ emotional experiences. Dunlap-Shohl presents his degeneration from Parkinson’s as being offset with the autonomy he gains, in part, through his relationships, which include his relationships with his clinicians.

Conclusion

Graphic medicine is useful for explaining patient autonomy to students through media that is amenable to teaching and learning about the diversity and individuality of patient experiences. Marbles and My Degenerationprovide trainees with different experiences of patient autonomy that can increase their ability to understand and express regard for patients whose autonomy and sense of agency can be undermined by illness. Forney elucidates the importance of self-trust and trust between physician and patient and how these two types of trust affect decision making and patient autonomy in the case of a mood disorder. Dunlap-Shohl helps readers understand the importance of diagnosis delivery and its dramatic impact upon a patient’s autonomy. By reading and discussing these accounts, trainees can combine principle-based medical ethics training about autonomy with experiential knowledge that aids in diagnostic and critical reasoning in ways that acknowledge patients’ emotional experiences. These previously underutilized resources provide trainees with tools to help cultivate their understanding of patient autonomy.

References

-

Czerwiec M, Williams I, Squier SM, Green MJ, Myers KR, Smith ST. Graphic Medicine Manifesto. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press; 2015.

- Williams IC. Graphic medicine: comics as medical narrative. Med Humanit. 2012;38(1):21-27.

-

Green MJ, Myers KR. Graphic medicine: use of comics in medical education and patient care. BMJ. 2010;340:c863. http://www.bmj.com/bmj/section-pdf/186501?path=/bmj/340/7746/Analysis.full.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2017.

- Yang G. Graphic novels in the classroom. Lang Arts. 2008;85(3):185-192.

- Green MJ. Teaching with comics: a course for fourth-year medical students. J Med Humanit. 2013;34(4):471-476.

- Williams RM. Image, text, and story: comics and graphic novels in the classroom. Art Educ. 2008;61(6):13-19.

- Jacobs D. More than words: comics as a means of teaching multiple literacies. English J. 2007;96(3):19-25.

- Cohn N. Un-defining “comics”: separating the cultural from the structural in “comics”. Int J Comic Art. 2005;7(2):236-248.

- Whitlock G. Autographics: the seeing “I” of the comics. MFS Mod Fict Stud. 2006;52(4):965-979.

-

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001:58.

-

Mackenzie C, Stoljar N. Introduction: autonomy refigured. In: Mackenzie C, Stoljar N, eds. Relational Autonomy: Feminist Perspectives on Autonomy, Agency, and the Social Self. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000:3-31.

- Tekin Ş. Self-concept through the diagnostic looking glass: narratives and mental disorder. Philos Psychol. 2011;24(3):357-380.

-

McLeod C, Sherwin S. Relational autonomy, self-trust, and health care for patients who are oppressed. In: Mackenzie C, Stoljar N, eds. Relational Autonomy: Feminist Perspectives on Autonomy, Agency, and the Social Self. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000:259-279.

- Entwistle VA, Carter SM, Cribb A, McCaffery K. Supporting patient autonomy: the importance of clinician-patient relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):741-745.

- Joannou SL. Toward an account of relational autonomy in healthcare and treatment settings. Essays Philos Humanism. 2016;24(1):1-20.

- Hébert P, Meslin EM, Dunn EV, Byrne N, Reid SR. Evaluating ethical sensitivity in medical students: using vignettes as an instrument. J Med Ethics. 1990;16(3):141-145.

- Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117-125.

-

Forney E. Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me: A Graphic Memoir. New York, NY: Gotham Books; 2012.

-

Forney, 15-18.

-

Forney, 19.

- Forney, 96..

-

Dunlap-Shohl P. My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press; 2015.

-

Dunlap-Shohl, 24-29.

-

Dunlap-Shohl, 84-85.

-

Dunlap-Shohl, 17-19.

-

Dunlap-Shohl, 8-9.

-

Dunlap-Shohl, 8-10.

-

Dunlap-Shohl, 71.