Abstract

Racism is responsible for the maldistribution of power in society and manifests as persistent disparities in maternal health among Black women in the United States. Testimonial injustice is an expression of prejudice that uses identity to undermine individuals’ credibility as authoritative “knowers” of their own bodies, selves, and experiences. Among Black women, experiences of testimonial injustice in health care encounters are common and likely contribute to disparities in Black maternal health. To promote more equitable power distribution and prioritize testimonial justice in clinical encounters, this article proposes a conceptual framework for fostering critical-racial consciousness among health professions students and trainees. The goal is for critical-racial consciousness development and refinement to stimulate antiracist actions in medical decision making and, ultimately, lead to a more equitable health care system in which Black women can thrive.

Of course innocent mistakes occur, but the accumulated insults and indignations caused by racial presumptions are destructive in ways that are hard to measure. Constantly being suspected, accused, watched, doubted, distrusted, presumed guilty, and even feared is a burden borne by people of color that can’t be understood or confronted without a deeper conversation about our history of racial injustice.

Bryan Stevenson1There must exist a paradigm, a practical model for social change that includes an understanding of ways to transform consciousness that are linked to efforts to transform structures.

bell hooks2

Reproductive Health Inequity

In the United States, Black women are 3 to 4 times more likely to die of a complication of pregnancy than White women.3,4 The COVID-19 pandemic widened these disparities: in 2020 and 2021, Black women had the highest maternal mortality rate of all racial groups and the largest increase in mortality rate from 2018.5 The magnitude of this inequity is also mirrored in disparities between Black and White women in severe maternal morbidities,6 and it will likely be exacerbated by the overturning of Roe v Wade: one study estimates a total abortion ban will yield a 21% increase in maternal deaths among all women and a 33% increase among Black women.7,8

While abhorrent, these inequities are nothing new. They are well documented across all stages of the reproductive health cycle and persist despite significant diagnostic and therapeutic medical advances.9,10 The insidious and seemingly unalterable nature of these inequities reflects something so deeply rooted in society that one can only describe it as foundational. Many health equity scholars have argued that the foundation and root cause of these inequities is structural racism.11,12,13

Structural racism refers to what Bailey et al call “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and criminal justice.”14 This poisonous legacy has systematized inequities in hospitals,15,16 been reinforced through ahistorical and biased medical curricula,17,18 and leaked into clinicians’ interpersonal interactions with patients wherein their assignment of value is implicitly or explicitly based on patient identity. In consequence, data gathering, diagnostic reasoning, and therapeutic choices are biased, ultimately affecting patient safety and experience.19,20

Crucially, structural racism and its attendant interpersonal prejudices create health inequities that directly reflect the power distribution within US society. This power distribution is recreated and sustained in the patient-clinician relationship. Currently, power within the patient-clinician relationship implicitly belongs to the clinician. In the health care encounter, clinicians are viewed as “knowledge holders” due to their professional status and, accordingly, hold the greatest power in the treatment process. Power can also be assigned to patients as “knowers” of their bodies, enabling them to provide history to support the therapeutic process. However, structural racism and discrimination stemming from interpersonal prejudice affect from which patients credibility as knowers is withheld—a phenomenon philosopher Miranda Fricker describes as testimonial injustice.21 Frequent occurrences of testimonial injustice in health care interactions likely contribute to existing racial disparities in Black maternal health outcomes. To ensure more equitable distribution of power and the prioritization of testimonial justice in clinical encounters, we propose a conceptual framework for fostering critical-racial consciousness among health professions students and trainees. We argue that the cultivation and refinement of critical-racial consciousness will catalyze antiracist actions in medical decision making, foster a flattened hierarchy that equally values the contributions of patients and clinicians and thus allows for truly collaborative decision making, and ultimately lead to a more equitable and just health care system wherein Black women can thrive.

Testimonial Injustice

For Black women, testimonial injustice occurs when their words are assigned less credibility in the treatment process because of their racial and gendered identities. Just as the term hysterical is recognized as a gendered reflection of sexism used to discredit a woman’s complaints, so too are many stereotypes at the intersection of race, gender, and socioeconomic position (eg, the irrational “angry Black woman,” the Black single mother, the “welfare queen,” and the sexually promiscuous “Jezebel ”) used repeatedly to discredit Black women’s knowledge and experiences.22,23,24 As a result, Black women patients are often omitted from participation in their own treatment, an injustice that results in misdiagnosis, dismissal of serious concerns, and disregard for the clinical warning signs that precede severe adverse outcomes, including death. Regrettably, the state of Black maternal health in the United States is a stark example of the repercussions of testimonial injustice. Numerous Black maternal morbidity and mortality cases have garnered media attention, specifically for how testimonial injustice contributed to these outcomes.25,26,27,28 The resulting activist movements, with names like “Believe Black Women” and “#Trust Black Women,”29,30 emphasize the importance of recognizing and valuing the experiences and voices of Black women in health care settings. These movements underscore that listening to Black women is a means to prevent adverse outcomes. Practices of discrediting Black women as credible knowers of their bodies and conditions is a manifestation of the power imbalance caused by structural racism. We argue that this quotidian practice is perpetuated by mutually reinforcing educational and health care systems. Ultimately, the practice contributes to the persistence of Black maternal health inequities in the United States.

Righting Testimonial Injustice

To create different, more equitable, outcomes for Black women, clinicians must learn to (1) interrogate structural racism and its resulting power imbalances in their profession and (2) engage in actions that disrupt the status quo of biased credibility assignment. Accordingly, we advocate for an enhanced medical education curriculum that incorporates critical analysis and reflection and uses critical pedagogy to achieve this objective. Critical pedagogy describes practices that medical educators can use to guide their students toward critiquing and countering discriminatory practices such as testimonial injustice.31 We recommend that medical educators use critical pedagogy to support students’ critical consciousness development, which in turn will enhance students’ ability to actively redistribute power within their own patient-clinician relationships in the service of testimonial justice and Black maternal health equity.

To support our recommendation, we share our interdisciplinary perspectives as Black cisgender women, mothers, and aunties whose scholarship is grounded in Black feminist thought and spans the fields of medicine, health disparities, early childhood development, and education disparities. We work on challenging systemic and personally mediated forms of racism that contribute to inequities for Black women. Here, we provide an orienting framework at the intersection of medicine and education to address the injustices that allow these inequities to persist.

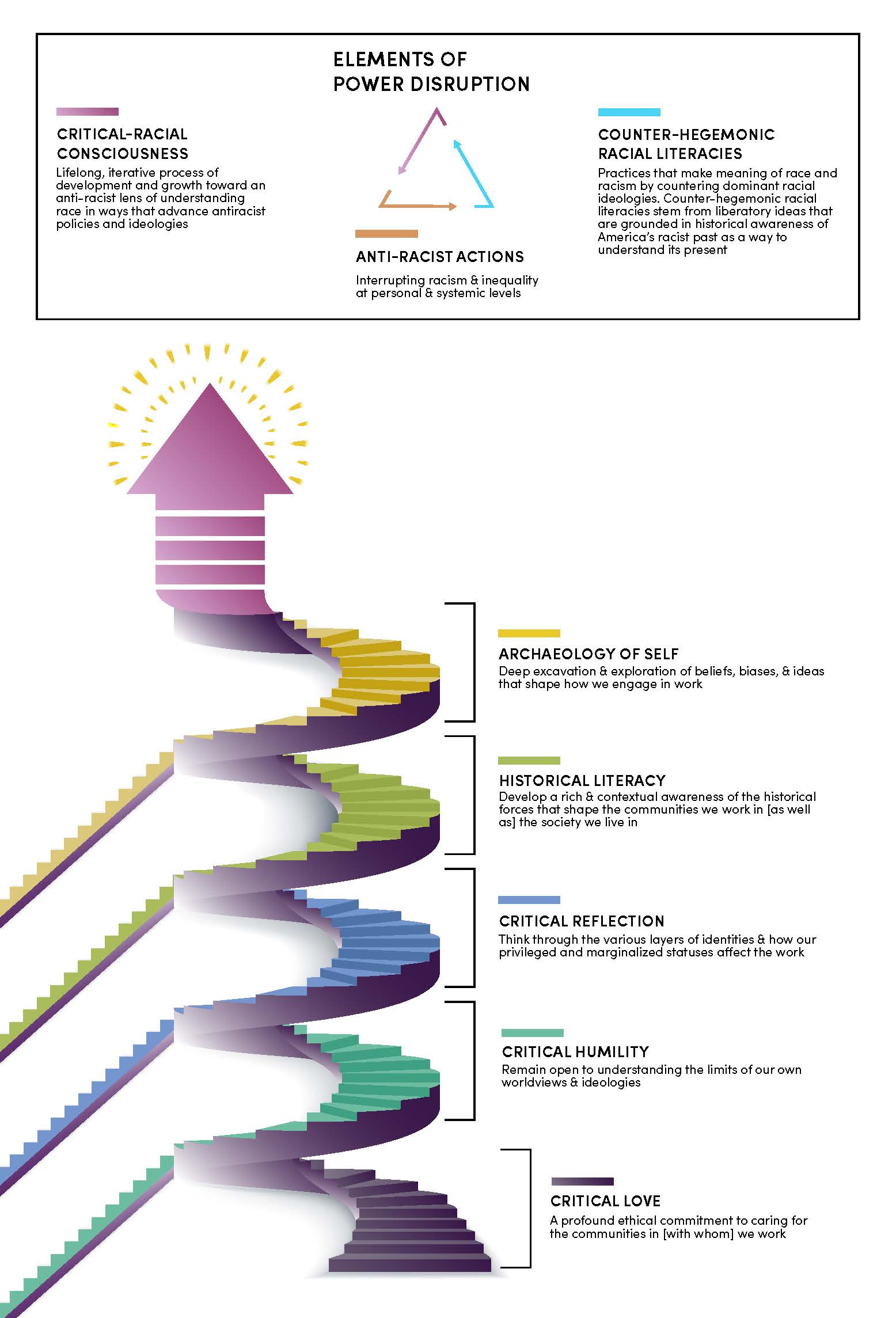

We propose a conceptual framework for critical-racial consciousness development as a tool for health professions educators and their students to redistribute power and promote testimonial justice within patient-clinician relationships (see Figure). Critical-racial consciousness derives from the foundational framework of critical consciousness proposed by Paolo Freire32 and is infused with the urgency of addressing racial dynamics in a society marked by evasive attitudes toward race.33 Critical-racial consciousness encapsulates an antiracism that not only identifies instances of racial inequalities but also steadfastly resists dominant ideologies and practices that reinforce racial hegemony. Our framework combines the work of 2 critical race and education scholars: Laura Chávez-Moreno33 and Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz.34 We intend for medical educators to reference this model and use it as a guide for students (and themselves) to develop a deeper awareness of how power functions within patient-clinician relationships. We also intend for educators and students to take actions to disrupt the power, authority, and credibility dynamics that maintain testimonial injustice in clinical encounters. While pursuing equity and justice for Black mothers inspired these recommendations, the proposed framework may be useful for advancing health equity for other historically marginalized patients experiencing inequity whom racism has attempted to render voiceless.

Figure. Conceptual Framework for Critical-Racial Consciousness Development

Framework based on Chávez-Moreno33 and Sealey-Ruiz.34

The Figure describes the capabilities that individuals develop along their path toward critical-racial consciousness. The figure’s winding nature and the arrow at the top suggest a step-wise process without a defined endpoint—a continuous journey toward higher levels of critical-racial consciousness. Critical love is the foundational first step, but the other elements have no predetermined sequence. Each can be used as power-disrupting critical pedagogy. Students can arrive at and reengage with any component based on their specific need for clarity, reflection, and understanding. Importantly, critical-racial consciousness does not exist as a distinct practice, but rather operates symbiotically and along a continuum with counter-hegemonic literacies and antiracist action. This relatedness is symbolized as a triangle at the top of the figure, wherein each element that aids in power disruption makes up one leg of the triangle.

Developing Critical-Racial Consciousness

Here, we describe the elements of the critical-racial consciousness development framework and examples of how each component can be used to disrupt power inequities in health care settings in order to support health professions educators’ use of the model as a tool for critical pedagogy.

Critical love. Sealey-Ruiz defines critical love as a “profound ethical commitment to caring for the communities we work in.”34 In the context of health equity, this commitment must extend beyond care delivery to overcoming the withholding of credibility that defines testimonial injustice. To critically love patients, clinicians must commit to recognizing their humanity and seeing them as intrinsically valuable. Critical love helps clinicians extend credibility to their patients despite stereotypes about socially constructed categories (eg, race and gender) that are used to describe—or, more concerningly, denigrate—patients. Cornel West defines love as tenderness in private moments and a willingness to speak about injustices in public moments.35 Black women deserve kindness and respect in private, interpersonal interactions with clinicians. They also deserve clinicians who publicly advocate for them when withholding credibility from them silences their voices.

We suggest that medical educators emphasize critical love as a competency for medical students. Students should understand that humanism and intrinsic-value appraisal resulting from critical love ultimately support a more accurate diagnosis.

Critical humility. Sealey-Ruiz defines critical humility as a willingness to “remain open to understanding the limits of our own worldviews and ideologies.”34 Medicine is a discipline with inherently paternalistic, hierarchical, and patriarchal ideologies. These ideologies privilege specific ways of knowing, particularly those of authority figures (eg, physicians) and those grounded in objective data (eg, lab or imaging results). Critical humility asks clinicians to consider that medicine’s ideologies protect rather than challenge privileged ways of knowing. More pragmatically, critical humility permits clinicians to say to their patients, “I don’t have all the answers; I need your help to figure this out,” or “I believe you and your concerns despite some of the data in front of me,” to disrupt clinician-privileged power dynamics. Critical humility allows clinicians to center ways of knowing of Black women and other historically marginalized people—such as intuition. These ways of knowing may oppose ways of knowing traditionally privileged in medicine.

Health profession educators can support students’ journeys toward critical humility by modeling how to interrogate the history of medical education and guiding students to consider how structural racism is evident even in standard medical practice. Specifically, educators can teach students to question how structural racism can lead to erroneous assumptions and biased decision making. For example, medical students’ inclusion of race in the history of present illness may inadvertently create anchoring biases and prematurely narrow differential diagnosis to a set of illnesses presumed to be correlated with specific racial categorizations. Educators can guide students to reflect on this traditional practice and why it might be problematic. Alternatively, students can ask patients about their experiences of racism, include this information in the social history, and consider its implications for the diagnostic workup.

Critical reflection. Sealey-Ruiz defines critical reflection as the ability to “think through the various layers of our identities and how our privileged and marginalized status affect our work.”34 Critical reflection allows one to think about the positions of unearned privilege and disadvantage that one simultaneously occupies.36 Often, people who hold positions of unearned privilege unilaterally seek to improve disadvantaged groups’ conditions—but without seeking the expertise of those with lived experiences of disadvantage. As a result, their strategies to address inequitable conditions tend to be incomplete, lacking the perspectives necessary for comprehensive, effective, and equitable solutions.

Practices of discrediting Black women as credible knowers of their bodies and conditions contributes to persistence of Black maternal health inequity in the United States.

One practical way to partner with patients through critical reflection is to ask whether you, as a clinician, are missing anything. Are you making assumptions about patients’ needs, access, or diagnosis and treatment? Collaboration with the patient can help answer these questions. For example, a Black, cisgender female clinician without disabilities may simultaneously have unearned privilege through heterosexuality and ability and unearned disadvantage through race and gender. It may be difficult for this clinician to understand the access challenges faced by her Black female patient with disabilities. Without critical reflection, she may offer resources based on her own experiences without honoring the patient’s expertise, thereby reducing the patient’s credibility as a knower. By contrast, critical reflection privileges a patient’s experiences over the clinician’s. Critical reflection helps clinicians consider multiple identity factors and choose an alternative path to invite patients to participate. Clinicians can even ask patients to educate them on what they need. This frame shift disrupts the power imbalance caused by unearned privilege and allows clinicians to serve their patients more constructively.

Historical literacy. Black maternal health provides a case study of the importance of historical literacy, which Sealey-Ruiz defines as the ability “to develop a rich and contextual awareness of the historical forces that shape the communities we work in but also the society we live in.”34 As Dorothy Roberts elucidates in Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty,37 the racist assault on the reproductive freedoms of Black women in the United States that began with the transatlantic slave trade still endures. Black women have been forced to bear children resulting from sexual assault. Eugenic ideologies have led to state-sanctioned control of Black women’s reproductive capacity (eg, unauthorized, unnecessary hysterectomies and social and economic rewards for implantable contraceptives).11,37 Moreover, media stereotypes from the 1970s through the 1990s of Black mothers as welfare queens who had children to profit from social services have contributed to a credibility and integrity assault on Black women that persists. These narratives have profoundly impacted how Black women approach reproductive care and help explain some of the tentativeness of Black women toward the health care system.

Historical literacy is about teaching history and allowing history to shape a clinician’s belief in a patient’s credibility. For example, a Black pregnant person who withholds information about drug use may not be intentionally lying but instead be rightfully mistrustful of presenting the full facts. They may withhold information because they know of the disproportionate penalties faced by Black mothers who use substances,38 such as prejudicial engagement with child protective services that recreates the dismantling of families reflective of the antebellum period.

In practice, teaching historical literacy may look like providing students with patient-care scenarios and asking them to think about the sociological and historical implications of their diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. This approach is about critical questioning. Why are students making their decisions? Based on what evidence? What might they be missing, informed by their historical understanding of structural racism? Students need ample time to practice suspending their assumptions and filtering them through lenses of privilege, historical knowledge, and biases in medicine and medical education.

Archaeology of self. Sealey-Ruiz defines the archaeology of self as “deep excavation and exploration of beliefs, bias, and ideas that shape how we engage in work.”34 It involves hard and sometimes painful self-reflection and self-critique. Unlike critical humility—which involves questioning what one knows and how one knows it and being willing to see things differently—or critical reflection—which requires considering how one’s privilege can color decision making and judgment—archaeology of self requires, in our model, an individual willingness to acknowledge structural racism in society and examine its implications for how one sees the world. It is not necessarily about privilege or knowledge, as critical reflection and critical humility are. It is about recognizing the impact of society (in this case, structural racism) on the individual, in whatever ways that impact materializes, and how that impact informs attitudes and behavior.

This personal examination of heart and mind may include journaling about how one’s upbringing was affected by race and culture. Archaeology of self may often feel displaced in educational spaces, as if we shouldn’t attend so closely to personal experiences as they relate to our profession. However, it is problematic when we don’t acknowledge that we bring our entire selves as practitioners when engaging with patients. It would be negligent to ignore the potential influence of personal experiences on professional outcomes.

Critical race consciousness—the culmination of these 6 steps—does not exist as a distinct practice from counter-hegemonic literacies and antiracist action. Chavez-Moreno characterizes the relationships among the three in the following way: “Antiracist actions and [counterhegemonic] literacy practices both emanate from and help produce critical-racial consciousness.”33 These closely related elements share a symbiotic relationship that iteratively leads to change (ie, power disruption). We discuss them below and describe their tri-directional relationship (see Figure) and their role in power disruption.

Counter-hegemonic racial literacy. In education, the concept of literacy extends beyond basic reading and writing skills to encompass the broader process of meaning making through sociocultural practices surrounding text and discourse. When students attempt to make meaning of race and racism, they can do so through (1) hegemonic racial literacies (ie, oppressive ideologies that uphold inequitable power structures, limit critical thinking, and downplay the social construction of race, hindering solutions for equity and justice) or (2) counter-hegemonic racial literacies (ie, anti-oppressive ideologies that challenge dominant narratives and power structures, foster a deeper understanding of the historical and sociocultural aspects of race, encourage critical analysis and questioning of racial hierarchies, and explore transformative solutions to address racial inequities).33

As Chavez-Moreno points out, “Educational institutions play an important role in providing people with formal and informal lessons about race and justice, even in lessons that do not explicitly focus on racial issues.”33 For example, using race in medical risk calculators promotes the false notion that race is a biological determinant of health. It overlooks the influence of social determinants of health (SDOH), such as poverty, education, access to health care, and discrimination. Overlooking SDOH may result in overestimating risks for certain racial groups and underestimating risks for others, creating unequal access to appropriate interventions and resources.39 In obstetrics, an example is using race in calculations of the probability of successful vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC). The older VBAC calculator includes a correction factor for race/ethnicity40 (which has since been removed41). Because the older calculator lowers the estimated success rate and raises the risk of unsuccessful VBAC for Black and Hispanic women, it may have predisposed clinicians to recommend cesarean sections instead of supporting VBAC attempts, leading to unnecessary surgical interventions.41

Antiracist actions. Antiracist actions are deliberate efforts to challenge and dismantle racism in all its forms. For clinicians, these actions can include impartial approaches to diagnostic reasoning, sharing clinical decision making with patients, and direct advocacy for patients. For example, a clinician may encounter a patient with unexplained pain who is unjustly labeled as “drug seeking” due to the patient’s race and socioeconomic background. The clinician can take action to counter the racism faced by the patient. This action may involve obtaining a new medical history without pretense or preconceived notions, inquiring about the patient’s experiences of racism and other forms of harm, and actively acknowledging biases that may have influenced prior diagnoses. The clinician can then reassess the initial differential diagnosis and advocate for additional diagnostic testing. This proactive approach helps clinicians broaden the scope of possibilities, including diagnostic options that were previously overlooked. Of course, antiracist actions can also extend to advocacy outside of the clinical encounter—such as political advocacy against police brutality, which has a known impact on maternal mental health.42

Critical-racial consciousness. Development of critical-racial consciousness is an ongoing and evolving process. It involves recognizing and critically examining how race intersects with power, privilege, and societal oppression. Individuals with critical-racial consciousness actively engage in self-reflection, education, and dialogue to challenge and dismantle racist attitudes within themselves and racist structures across broader systems. This dynamic process involves consciously choosing which aspects of the critical-race consciousness development framework require attention in any given situation. The continuous development of critical-race consciousness enables individuals to navigate and challenge racial dynamics in a more informed and intentional manner.

The symbiotic relationship among critical-racial consciousness, counter-hegemonic racial literacies, and antiracist actions offers students awareness, knowledge, and an opportunity to disrupt the power dynamics that enable testimonial injustice. Instructors and students gain new and increasing awareness of structural racism and its impact on their daily lives, including on their roles as medical students and clinicians, as they progress through elements of the model in the Figure and take action in their clinical practices to extend testimonial justice to Black women and other historically marginalized populations.

References

-

Stevenson B. Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption. One World; 2015.

-

hooks b. Killing Rage: Ending Racism. Holt; 1996.

- MacDorman MF, Thoma M, Declcerq E, Howell EA. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal mortality in the United States using enhanced vital records, 2016-2017. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(9):1673-1681.

-

Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed March 23, 2020. Accessed January 21, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm

-

Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2021. National Center for Health Statistics; 2023. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2021/maternal-mortality-rates-2021.pdf

-

Liese KL, Mogos M, Abboud S, DeCocker K, Geller S. Racial disparities in severe maternal morbidities across the pregnancy continuum in the United States [17A]. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:13S.

- Stevenson AJ. The pregnancy-related mortality impact of a total abortion ban in the United States: a research note on increased deaths due to remaining pregnant. Demography. 2021;58(6):2019-2028.

-

Artiga S, Hill L, Ranji U, Gomez I. What are the implications of the overturning of Roe v Wade for racial disparities? Kaiser Family Foundation. July 15, 2022. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/what-are-the-implications-of-the-overturning-of-roe-v-wade-for-racial-disparities/

- Thompson TM, Young YY, Bass TM, et al. Racism runs through it: examining the sexual and reproductive health experience of black women in the South. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(2):195-202.

- Chinn JJ, Martin IK, Redmond N. Health equity among Black women in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(2):212-219.

- Taylor JK. Structural racism and maternal health among Black women. J Law Med Ethics. 2020;48(3):506-517.

- Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Lewis Johnson T, McLemore MR, Neilson E, Wallace M. Social and structural determinants of health inequities in maternal health. J Womens Healtyh (Larchmt). 2021;30(2):230-235.

- Owens DC, Fett SM. Black maternal and infant health: historical legacies of slavery. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1342-1345.

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463.

- Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(2):143-152.

- Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):122.e1-122.e7.

- Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, et al. Misrepresenting race—the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):872-878.

-

Khan S, Mian A. Racism and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(9):1009.

- Gopal DP, Chetty U, O’Donnell P, Gajria C, Blackadder-Weinstein J. Implicit bias in healthcare: clinical practice, research and decision making. Future Healthc J. 2021;8(1):40-48.

-

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19.

-

Fricker M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press; 2007.

- Ashley W. The angry black woman: the impact of pejorative stereotypes on psychotherapy with black women. Soc Work Public Health. 2014;29(1):27-34.

- Reynolds-Dobbs W, Thomas KM, Harrison MS. From mammy to superwoman images that hinder Black women’s career development. J Career Dev. 2008;35(2):129-150.

-

Hill Collins P. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge; 2009.

-

Martin N, Montagne R. The last person you’d expect to die in childbirth. NPR. May 12, 2017. Accessed December 23, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2017/05/12/527806002/focus-on-infants-during-childbirth-leaves-u-s-moms-in-danger

-

Williams S. Serena Williams: what my life-threatening experience taught me about giving birth. CNN. February 20, 2018. Accessed April 6, 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2018/02/20/opinions/protect-mother-pregnancy-williams-opinion/index.html

-

Villarosa L. Why America’s Black mothers and babies are in a life-or-death crisis. New York Times. April 11, 2018. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html

-

Villarreal A. New York mother dies after raising alarm on hospital neglect. Guardian. May 2, 2020. Accessed September 11, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/02/amber-rose-isaac-new-york-childbirth-death

-

Believe Black women. New Jersey Black Women Physicians Association. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.njbwpa.com/believeblackwomen

-

Trust Black Women. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://trustblackwomen.org/home

-

Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 50th anniversary ed. Bergman Ramos M, trans. Bloomsbury Academic; 2018.

-

Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. Bergman Ramos M, trans. Seabury Press; 1973.

- Chávez-Moreno LC. Critiquing racial literacy: presenting a continuum of racial literacies. Educ Res. 2022;51(7):481-488.

-

Sealey-Ruiz Y. The critical literacy of race: toward racial literacy in urban teacher education. In: Richard Milner H, Lomotey K, eds. Handbook of Urban Education. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2021:281-295.

-

West C. Cornel West on “tenderness” in education. Harvard Graduate School of Education Facebook page. October 4, 2017. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=10155292829161387

-

Nixon SA. The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: implications for health. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1637.

-

Roberts DE. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. 2nd ed. Vintage Books; 2017.

- Chasnoff IJ, Landress HJ, Barrett ME. The prevalence of illicit-drug or alcohol use during pregnancy and discrepancies in mandatory reporting in Pinellas County, Florida. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(17):1202-1206.

- Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1125-1128.

- Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight—reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2021;76(1):5-7.

-

Grobman WA, Sandoval G, Rice MM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in term gestations: a calculator without race and ethnicity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(6):664.e1-664.e7.

-

Mehra R, Alspaugh A, Franck LS, et al. “Police shootings, now that seems to be the main issue”—Black pregnant women’s anticipation of police brutality towards their children. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:146.