Abstract

Identity and representation remain some of the most complex aspects of what it means to practice medicine. These themes’ plurality and diverse expressions are particularly challenging in medical school admissions decisions. This article offers a personal viewpoint on intersections among race, class, and culture and key roles each plays in driving equitable, inclusive admissions that motivate diversity in medicine.

Belonging

“Where are you from?” The questioner was an older, White man in the Veterans Affairs (VA) Greater Los Angeles (GLA) Healthcare System. I was a second-year medical student on the ophthalmology service. This question is not new to me. It is a way people have tried to place my toffee-colored complexion, relatively ambiguous features, and Hispanic-sounding last name.

“America,” I responded, with a smile.

I knew what he was asking. I was not one of the typical White male physicians he was used to seeing. He proceeded to talk about how wealthy I must be to come from another country (never mind that I just said I was from America) and afford an American medical education. The foreignness of my brown skin and prestige of my white coat intersected in one place for his schema: I must have been rich to enter the United States and this profession.

My response to him was an act of defiance. I answered “America,” although I was born in the Philippines and raised by a single mother of 4 children. I moved to the United States when I was 15 and enrolled in a high school notorious for gang violence and poor graduation rates.

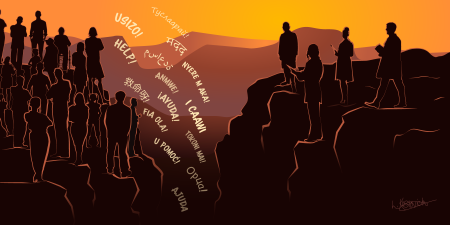

This encounter reminded me of how often I stood in the chasm between the dominant narrative of people in medicine and my own narrative, each instance marked as You don’t belong here.

Imposterism

In college, the term first-generation college student provided some context as to why SAT classes, international immersion experiences, and awards to winners in expensive sports were alien to me. I also learned of imposter syndrome, which captured my relentless self-doubt about whether I was smart enough or talented enough to legitimately exist in a predominantly White, affluent university. The more I encountered privilege among my fellow students, the more I suspected I was there by mistake. I believed I had to earn my keep. These thoughts persisted through my transition to medical school. I joined the student council and other extracurricular activities, spending precious energy getting to know my classmates, yearning to build community while striving to stay afloat academically. I was committed to earning a sense of belonging.

As a Filipino, I am Asian, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander. The US census and countless studies often categorize Filipinos as Asian, although our history and culture deviate distinctly from those of East and South Asian people. Three island groups of the Philippine archipelago exist in the Pacific Ocean, which has sustained and shaped the Filipino people since as far back in our country’s history as I have studied. For more than 300 years, Spain occupied the Philippines, and this colonial legacy emerged and still exists in our food, language, and multifaceted colorism. At times, I feel the strength of all these identities combined, but more often than I would like to admit, I feel like none of the above, other, an impostor in the United States.

Representation in Medicine

When applying to medical schools, I found only one medical school that considered Filipinos as underrepresented minorities (URMs) in medicine.1 If folks of my background were represented well enough, why did I not know any Filipino physicians? Where were all the Filipino doctors for the Filipino aunties, uncles, and grandparents I knew, who would have loved being cared for by a physician who shared and understood their experiences?

With each interview and acceptance notice from top schools, we celebrated—not just for him, but for our community.

A prevailing stereotype among some in the majority is that Filipinos make great nurses. I interviewed a patient once who asked, “Who are you, the nurse?” This question stirred in me simultaneously a sense of pride and erasure. I have deep respect for nurses. Some of my best teachers of medicine have been nurses, many of whom are Filipino. Yet I experienced this patient’s response as a purposeful questioning of my place in medicine, rooted in a flawed medical hierarchy that diminishes both the role of nurses and the plausibility of my budding into a Filipino physician.

Getting in

I was on the waiting list for my medical school for months before being accepted late in the admissions cycle, which exacerbated my sense of imposterism. Yet I was luckier than others whose applications were rejected under a recently changed admissions requirement, according to which applicants are screened using high Medical College Admission Test® (MCAT) scores and grade-point averages (GPAs).2 These criteria, which had already been in place for 2 admissions cycles, denied extending secondary application requests to about 95% of socially disadvantaged applicants, most of whom are minorities. During my first year as a medical student, the student body learned of this admissions policy, which was adopted almost exclusively by White men. Students had been concerned about the downtrend in our program’s diversity, and this revelation cast a cloud over the school. In the shadow of that cloud, many students grappled with self-doubt and the thought that they would not be here had these admissions criteria been applied to them. Trust among students, administrators, faculty, and admissions committee members crumbled.

During that admissions cycle, a dear friend was applying to medical schools. He was brilliant, with research accolades and a strong record of health equity and social justice advocacy. He was also a first-generation Filipino from a low-income background. With each interview and acceptance notice from top schools, we celebrated—not just for him, but for our community. Although my medical school was his top choice, he did not pass the primary screen of applications. His MCAT score was one point below the new threshold.

When I revealed to him the admissions changes, I could not help but feel a deep sense of sadness. I mourned his loss of a chance to pursue medical education close to his family. I mourned not having one more Filipino person who understood my convoluted thoughts regarding identity, inclusion, and invisibility.

I was angry, too. Data show that applicants with lower GPAs and MCAT scores successfully transition to second year and do well on Step 1 of the United States Medical Licensing Examination® (USMLE).3 My friend was among many URMs whose talents, perspectives, and experiences my institution neglected to value.

Our voices were eventually heard. The following application cycle brought more diverse interviewees. I saw a premed colleague whose MCAT score was lower than the prior year’s threshold. During student council meetings with faculty and administrators, I observed subtle yet powerful shifts in how people engaged in conversations about holistic admissions review and acknowledged structural barriers faced by URMs. Perhaps it was a town hall meeting where students and alumni spoke boldly about their experiences to protest admissions policy changes. Perhaps it was a deep dive into data or candid conversations about our school’s values. Perhaps it was the acts of resistance by students, faculty, and administrators who, in their respective spheres, strive to make medicine more equitable. Our advocacy bore fruit. And we continue to fight for those who are not yet admitted but who deserve to be.

Being From America

When strangers, including patients, ask me where I am from, my response—“I am from America”—means my story of immigrating to the United States is not subject to trial and scrutiny. “I am from America” means I transform feeling othered into a means of trying to help patients and communities left at the margins. “I am from America” means I choose to believe what’s contrary to what I had been conditioned to believe. I do, in fact, belong here in America, here in medicine. Today and each day, that is true, and that is enough.

References

-

URM definition. Office of Diversity and Outreach, University of California, San Francisco. Accessed December 2, 2019. https://diversity.ucsf.edu/URM-definition

-

Using MCAT® data in 2019 medical student selection. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2018. Accessed October 23, 2020. https://www.scribd.com/document/433319759/MCAT-Guide

-

Using MCAT® data in 2020 medical student selection. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019.