Abstract

Forced sterilization has a long history in the United States. Because sterilization requires surgical skill, physicians have been the lone professionals engaging in this practice, although they were not the only experts or Americans to hold eugenic and neo-eugenic views. But physicians have also been whistleblowers who exposed sterilization abuse and led efforts to end it. The commentary on this case suggests that physicians should respond along those lines.

Case

During her outpatient obstetrics clinic, Dr P saw MT. MT first came to see Dr P at age 24. At that time, she had given birth to 5 children and had normal periods and hormone levels. Now 34 years old and recently released from prison, MT explains that she delivered her most recent child via cesarean delivery at the age of 30, while she was in prison. She wishes to become pregnant again but has been unable to do so for the past 10 months and now seeks Dr P’s help.

MT’s recent physical examinations and lab test results were normal, so Dr P thought her inability to conceive over the last 10 months might be due to infertility in her new husband. Testing revealed, however, that his sperm’s motility and numbers were normal. Dr P then ordered a hysterosalpingography, a fluoroscopic x-ray of the uterus and fallopian tubes, to see if MT had developed an obstruction, perhaps from scarring after a chlamydia infection for which she was successfully treated as a teen. Dr P is shocked to see that the hysterosalpingography reveals that MT had undergone a tubal ligation.

Dr P has no good reason to believe that MT knows that she had a tubal ligation. When Dr P tells MT that she has had a tubal ligation, she sits silently for a moment and then begins to cry. “They made me sign something right before the Caesarean section. I was drugged. That’s when they did it. What can we do now?”

Commentary

MT’s story is a familiar one. Tens of thousands of Americans have been involuntarily sterilized since the turn of the 20th century.1 MT’s experience represents the most recent iteration of this practice—forced sterilization of women in prison—but it is not unique. In its earliest form, sterilization in America followed eugenics, the so-called science of racial betterment. Scientists and clinicians engaged in this field of study, and many policymakers drew on eugenic research when calling for an end to immigration in the 1910s and 1920s.2,3 Eugenicists offered segregation and sterilization as solutions to the so-called problem of the unfit and the social ills they supposedly embodied and reproduced.2,3 But physicians have also been whistleblowers who exposed sterilization abuse and led efforts to end it.

Coercive Sterilization History

In 1927, the US Supreme Court upheld Virginia’s eugenic sterilization law in the landmark case of Buck v Bell, in which Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr famously declared, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”4 By 1942, 30 states had adopted similar eugenic statutes,2 and sterilization rates skyrocketed. Before Buck, a few hundred sterilizations were performed annually, and 3233 individuals had been sterilized for eugenic reasons.2 After Buck, between 2000 and 3000 Americans were eugenically sterilized every year.2 By 1941, at least 38 087 citizens had been eugenically sterilized.2 However, as historian Paul Lombardo makes clear, we do not know the actual number of eugenic sterilizations performed in the United States, because not all of them were recorded or officially counted.1 Most sterilizations were performed on women because women bore children and because, before Buck, men who had been sterilized in prison (to make them more docile) successfully charged that their vasectomies constituted cruel and unusual punishment.2,5,6

American eugenicists, including health care professionals, positioned themselves as at the forefront of international eugenics. Worldwide, they participated in conferences, published articles, received honorary degrees, and corresponded with eugenicists in other countries—most notably, Germany.7 Nazi policymakers based eugenic laws and programs on American legislation and courted support of leading American eugenicists from the 1930s through the early years of World War II.7 Indeed, Nazi policymakers held up American, eugenics-informed immigration policy as a model of racial preservation.7 The US immigration laws of 1921 and 1924 restricted immigration of persons with hereditary diseases and of persons from Eastern and Southern Europe, Africa, and Asia. Nazis scrutinized American eugenic research, including the infamous family studies of the Jukes and the Kallikaks that purported to prove the hereditability of so-called degenerate traits. Nazi scientists and policymakers used these studies to support precursors to the Final Solution.7

Mutual admiration between German and American eugenicists led Americans drawing on Nazi propaganda to spread ideas of supposed racial betterment.7 American eugenicists applauded German sterilization laws and “were the strongest foreign supporters of Nazi race policies.”7 California enacted more sterilization laws than any other US state and sterilized more people than any other US state,7 and its eugenicists enthusiastically expressed support for sterilization laws in Germany.3,7 Paul Popenoe and Eugene S. Gosney, president of the Human Betterment Foundation, the leading eugenics organization in the California, proved especially influential. Both men corresponded with German eugenicists and supported Nazi policies for years.7

Neo-eugenics and Family Planning

In the 1930s, opposition from the Catholic Church, geneticists, and social scientists stressed the importance of environment rather than genetics—nurture as opposed to nature—in shaping individual behavior. This opposition weakened eugenics.1,8 The number of eugenic sterilizations also declined when the US joined the allies in World War II, with surgeons now serving in the war.2 Sterilization did not rebound,2 but neither did it end.

Neo-eugenics. Ideas linking reproductive fitness to race continued to seep into clinical practice, public policy, and popular culture after World War II.9 Neo-eugenics framed poverty, illegitimacy, and criminality as culturally—not genetically—reproduced by women of color and drove a new wave of forced sterilizations from the 1950s through the 1970s.9 White postwar social anxiety about civil rights, overpopulation, Mexican and Puerto Rican immigration, and welfare state expansion under President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Great Society program undergirded these surgeries, which were nearly always performed by White male physicians on poor women of color.9 In the 1950s, North Carolina targeted poor Black women for sterilization under its existing eugenics law10,11 and “Mississippi appendectomies”—forced sterilizations of Black women who entered hospitals to undergo abdominal surgeries and, without their knowledge or informed consent, left without their uteruses—ran rampant across the South, especially in areas of intense civil rights action. Clinicians practiced White supremacy when they employed scalpels as tools of social control to demonstrate their resistance to Brown v Board of Education (1954) and other civil rights victories.9,12

Loyalty to one’s employer in following defined processes can strain one’s loyalty to the patient.

Family planning. Transformation of sterilization from a eugenic procedure into a legitimate form of contraception in the late 1960s and early 1970s hid rising rates of forced sterilization among American women.9 In 1960, the pill came on the market, boasting a nearly 100% success rate at preventing pregnancy.13 Despite uncomfortable side effects, millions of American women rushed to have prescriptions filled. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) offered similar benefits a few years later. But the 1969 pill scare13 and the 1974 Dalcon Shield IUD fiasco14 revealed deadly risks associated with these methods of contraception. Unwilling to return to messy, less effective diaphragms and condoms, American women and men began requesting sterilization, which many clinicians viewed as a safe, effective method of limiting fertility, preventing unplanned pregnancy, and reducing overpopulation—a new concern in the 1960s.9 Voluntary sterilization rates rose concurrently with federal family planning expansion in the late 1960s, unifying clinicians’ belief in sterilization as cost-effective contraception that could alleviate effects of poverty for patients whom they saw as vulnerable—most notably, poor women of color who received state-funded health care.9 When poor women were forcibly sterilized, their surgeries were included in voluntary sterilization tallies and rendered invisible.9

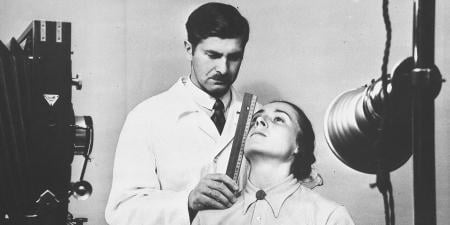

Clinician Intention and Authority

Most clinicians acted with benevolent intentions but often crossed ethical lines when they recommended sterilization to patients, especially poor women of color who did not request them. In an era when informed consent was a topic of conversation among clinicians but not standard practice, thousands of Black, Latina, and Native American women entered public hospitals to give birth and were sterilized after delivery without their informed consent. Some clinicians deceived patients into believing tubal ligation was reversible; some pressured patients to verbally consent during labor or while under the influence of pain medication; and others failed to use interpreters when communicating with patients with limited English language proficiency and pushed those patients to signify their consent on forms they did not understand.9

Occasionally, physicians were malicious, bullying pregnant and laboring women into sterilization by threatening to revoke care.15,16,17,18,19 Some with malevolent intentions blamed poor women of color for a host of social problems and put their scalpels to punitive use. One North Carolina physician crudely stated: “A doctor who had just got his income tax back and realized it all went to welfare and unemployment was more likely to push it [sterilization] harder.”9 Most physicians who sterilized women in the 1960s and 1970s acted within outdated standards of medical paternalism.9,20 These (mostly) White men viewed reproduction as a public rather than a private issue and believed their medical license gave them the social authority to determine who should bear children and who should not. They saw themselves as uniquely qualified to create social change on an individual level; sterilization required a surgeon’s skill, after all.

By the 1950s, most physicians were no longer general practitioners making house calls among patients in their communities but specialists caring for strangers in hospitals and clinics with new lifesaving technologies and drugs.21 Despite this change, many physicians continued to believe in their capacity, authority, and right to make life-changing decisions for their patients. Their patients, however, were beginning to challenge this authority and demand a greater role in the provision of their own health care.3,22,23,24 This clash of values eventually caused a reassessment of the patient-clinician relationship, but it was not soon enough to end the forced surgeries.25

Change, but Not Enough

In courtrooms and in the court of public opinion, victims of sterilization abuse bravely challenged the physicians who harmed them, forcing state and federal governments to confront the violence they suffered. The Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) established federal guidelines in February 1974 that required informed consent and prohibited sterilization of persons under 18 years of age.9 The National Welfare Rights Organization opposed the HEW guidelines in court based on their insufficiency to prevent abuse.9 A subsequent court order prompted HEW to prohibit sterilization of persons unable to consent or under 21 years of age.9 New York City established protections for public patients in 1975 that included a mandatory waiting period between consent and surgery.9 In 1976, California adopted similar guidelines that applied to all public and private patients seeking sterilization.9 State guidelines mandated waiting periods of between 14 days (California) to 30 days (New York) between consent and surgery, prohibited sterilization of minors, required consent in a patient’s native language, and provided model consent forms.9 In 1978, HEW adopted rules, including a 30-day wait mandate for all patients 21 years or older whose sterilizations were federally funded; continued a moratorium on sterilization persons unable to consent; and forbade sterilization of institutionalized persons unless their informed consent could be secured and reviewed by a board, a rule that sought to prevent the practice of sterilization among persons with intellectual and mental disabilities that dates back to the early 20th century.9

These policy changes significantly reduced, but did not end, sterilization abuse in America.18 Forced sterilization made national headlines again in the summer of 2013 when it was revealed that the California Department of Corrections had sterilized 148 female inmates between 2006 and 2010 without state approval—a significant violation because California outlawed forced sterilization in 1979 and in 1994 required clinical officials’ approval for elective sterilization of prisoners.26 MT’s sterilization fits the abuse profile of many women incarcerated during this period in California. It occurred in prison during a cesarean delivery and did not involve informed consent.

Whistleblowers and Advocates

A small group of physicians, many of whom were active in the civil rights movement, led efforts to end sterilization abuse.22,27 One year after news broke of the infamous US Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee,9 the Southern Poverty Law Center revealed that its clients in Relf vs Weinberger, Minnie Lee (age 12) and Mary Alice (age 14) Relf were sterilized by a Montgomery, Alabama, family planning agency whose personnel believed these young Black girls—one of whom had a disability—needed permanent pregnancy prevention.9 The Relf case made national headlines, and Senator Edward Kennedy invited the girls’ parents to testify at US Senate hearings.9

In the early 1970s, Bernard Rosenfeld, an obstetrics resident physician at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), County Hospital, exposed sterilization abuse of Mexican and Mexican-American women at his institution. Rosenfeld spoke to reporters, contributed to a Health Research Group report that documented abuse, and wrote to civil rights organizations.15,16 Attorneys Antonia Hernández of the Los Angeles Center for Law and Justice and Charles Nabarette took the case and filed a class action lawsuit against Edward Quilligan, chair of the UCLA Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Karen Benker, a UCLA medical student who also witnessed the abuse, testified on behalf of the plaintiffs. She and Rosenfeld directly and publicly challenged a leader in in their field, potentially imperiling their careers.15 After his first year of residency, Rosenfeld’s contract was not renewed. Rosenfeld believes this was retribution for his activism, although Quilligan cited unsatisfactory job performance.28 Psychiatrist Terry Kupers served as an expert witness and testified to the psychological damage that plaintiffs suffered as a consequence of their forced surgeries. When Madrigal v Quilligan was decided in favor of Quilligan in 1978,29 Kupers published an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times decrying the verdict.30

New York City adopted sterilization guidelines the same year Madrigal was filed. Helen Rodriguez-Trías spearheaded the collaboration between the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation and the grassroots Committee to End Sterilization Abuse that resulted in the guidelines. Rodriguez-Trías was raised and trained in Puerto Rico. She later moved to New York City, where she practiced at Lincoln Hospital, and became a leader in in the women’s health movement. Throughout her long career, which included serving as president of the American Public Health Association in 1993, Rodriguez-Trías promoted social change within medicine and on the streets.31,32

In the early 1970s, Constance Pinkerton-Uri, a Native American physician, raised public awareness of sterilization abuse on Indian Reservations after a patient requested a “womb transplant.” Pinkerton-Uri discovered that this patient, believing the surgery to be reversible, had undergone a hysterectomy 6 years earlier. Suspecting a long-term epidemic of similar sterilization abuse at Indian Health Service (IHS) sites nationwide, Uri consulted US Senator James Abourezk of South Dakota, who requested a federal investigation.33,34,35 The subsequent Government Accounting Office report revealed that 3000 tubal ligations had been performed between 1973 and 1976, 36 of which violated the 1974 federal prohibition against sterilization of women under age 21.36,37 Keenly aware of Native American women’s reluctance to seek care via the IHS because of the risk of sterilization, Uri and 2 colleagues began to hold clinical appointments in a tepee.9

Dr P’s Response

Dr P could stay quiet and focus on helping her patient come to terms with a surgery to which she did not consent and that robbed her of her fertility. But the history just outlined suggests that MT’s sterilization abuse was part of a broader nationwide pattern of systemic injustice. Dr P should inform state officials of her patient’s situation and suggest a thorough review of former and current prisoners’ health records in search of similar cases of abuse. Although Dr P cannot reverse MT’s sterilization, she can follow in the footsteps of her socially conscious physician predecessors who helped reduce sterilization abuse in America.

References

-

Lombardo P. Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v Bell. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2008.

-

Reilly P. The Surgical Solution: A History of Involuntary Sterilization in the United States. Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991.

-

Kline W. Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics From the Turn of the Twentieth Century to the Baby Boom. University of California Press; 2005.

-

Buck v Bell, 274 US 200 (1927).

- Carey A. Gender and compulsory sterilization programs in America, 1907-1950. J Hist Sociol. 1996;11(91):74-105.

-

Largent M. Breeding Contempt: The History of Coerced Sterilization in the United States. Rutgers University Press; 2011.

-

Kühl S. The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism. Oxford University Press; 2004.

-

Kevles D. In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. Harvard University Press; 1998.

-

Kluchin R. Fit to Be Tied: Sterilization and Reproductive Rights in America, 1950-1980. Rutgers University Press; 2009.

-

Schoen J. Choice and Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare. University of North Carolina Press; 2005.

-

Begos K, Deaver D, Railey J. Against Their Will: North Carolina’s Sterilization Program and the Campaign for Reparations. Gray Oaks Books; 2012.

-

Lee C. For Freedom’s Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. University of Illinois Press; 2002.

-

Watkins E. On the Pill: A Social History of Oral Contraceptives, 1950-1970. Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998.

-

Tone A. Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America. Hill & Wang; 2002.

-

Gutiérrez E. Fertile Matters: The Politics of Mexican-Origin Women’s Reproduction. University of Texas Press; 2008.

-

Rosenfeld B, Wolfe S, McGarrah R. A Health Research Group Study on Surgical Sterilization: Present Abuses and Proposed Regulations. Health Research Group; 1973.

-

Bogue T, Sigelman D. Sterilization Report Number 3: Continuing Violations of Federal Sterilization Guidelines by Teaching Hospitals in 1979. Health Research Group; 1979.

-

Siegelman D. Health Research Group Study Number 4 on Sterilization Abuse of Nation’s Poor Under Medicaid and Other Federal Programs. Health Research Group; 1981.

-

Krauss E. Hospital Survey on Sterilization Policies. American Civil Liberties Union; 1975.

-

Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry. Basic Books; 1982.

-

Rothman D. Strangers at the Bedside: A History of How Law and Bioethics Transformed Medical Decision-Making. Basic Books; 1991.

-

Nelson A. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination. University of Minnesota Press; 2011.

-

Dudley-Shotwell H. Revolutionizing Women’s Healthcare: The Feminist Self-Help Movement in America. Rutgers University Press; 2020.

-

Morgen S. Into Our Own Hands: The Women’s Health Movement in the United States, 1969-1990. Rutgers University Press; 2001.

-

Jonsen AR. The Birth of Bioethics. Oxford University Press; 1998.

-

Johnson CG. Female inmates sterilized in California prisons without state approval. Reveal. July 7, 2013. Accessed May 7, 2020. https://www.revealnews.org/article/female-inmates-sterilized-in-california-prisons-without-approval/

-

Dittmer J. The Good Doctors: The Medical Committee for Human Rights and the Struggle for Social Justice in Health Care. Bloomsbury Press; 2009.

-

Dreifus C. Sterilizing the poor. In: Dreifus C, ed. Seizing Our Bodies: The Politics of Women’s Health. Vintage Books; 1974:109-121.

-

Madrigal v Quilligan, 639 F2d 789 (9th Cir 1981).

-

Kupers T. 10 lose their fertility—and their case. Los Angeles Times. September 28, 1978:C7.

- Wilcox J. The face of women’s health: Helen Rodriguez-Trias. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):566-569.

-

National Library of Medicine. Dr Helen Rodriguez-Trias. October 14, 2003. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_273.html

- Lawrence J. The Indian Health Service and the sterilization of Native American Women. Am Indian Q. 2000;24(3):400-419.

- Torpy SJ. Native American women and coerced sterilization: on the Trail of Tears in the 1970s. Am Indian Cult Res J. 2000;24(2):1-22.

-

Theobald B. Reproduction on the Reservation: Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Colonialism in the Long Twentieth Century. University of North Carolina Press; 2019.

-

Staats EB. Letter report (HRD-77-3) investigation of allegations concerning Indian Health Service. Comptroller General of the United States; November 4, 1975. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/assets/120/117355.pdf

-

Miller M, Miller J, Szechenyi C. Native American peoples on the Trail of Tears once more. Akwesasne Notes. 1979;11(2):18.