Undocumented immigrant patients, constituting an estimated 11 million people,1 are among the most vulnerable groups in the United States. They are “disproportionately poor, non-white, and non-English speaking,”2 and without access to stable employment or health insurance. Anti-immigrant sentiment can shape policy, such as the Affordable Care Act of 2010, which limits participation in health care exchanges to immigrants who are “lawfully present.”3 Additionally, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 denied undocumented immigrants eligibility for federal public benefits and for state and local public benefits, with some exceptions,4 prompting many states and cities to create safety net programs for those immigrants adversely affected by this federal policy.5 Any cuts in funding at federal, state, and city levels to safety net health care facilities for underserved patients thus affect immigrant communities.6 Furthermore, a political climate that tolerates migration criminalization rhetoric has served to create what’s been called a chilling effect—reduction, due to fear rather than eligibility changes, in the number of undocumented immigrants willing to interact with staff at public agencies or enroll themselves or their children in health plans or other benefits.7

In this issue of the AMA Journal of Ethics, we explore ethical issues that arise when clinicians attempt to provide care to this extremely vulnerable population and, just as importantly, how the community of health professionals should advocate for these patients—including through self-education and the education of trainees and in the exam room and on Capitol Hill.

In this issue, several articles examine barriers to care for undocumented patients. Jonathan J. Suarez comments on difficulties accessing care that undocumented immigrants with end stage renal disease face, especially with regard to accessing regular dialysis care. Ruth L. Ackah, Rohini R. Sigireddi, and Bhamidipati V. R. Murthy write about the ethical issues that arise when children who undergo renal transplantation funded by Medicaid and charitable sources enter adulthood and are no longer able to afford regular follow up and immunosuppressive care. Rie Ohta and Clara Long shed light on a formidable set of obstacles to providing medical care in immigration detention centers, an issue that has received significant media attention this past year due the systematic separation of families at the border and the detention of children in substandard shelters. Rachel Fabi reviews national-level and state-level policies that affect access to prenatal care for this population and considers the ethical challenges these policies create.

In seeking to bridge the health care gap between undocumented immigrants and the general population, health systems and individual clinicians have created safety-net clinics, including community health centers as well as free clinics, often with the backing of academic institutions. These clinics may not possess a full range of services, and a very different standard of care is delivered to these patients. Peter Ellis and Lydia S. Dugdale address the question of how to define standard of care in resource-limited clinics and the challenges that free clinics face when delivering care to vulnerable populations. Robin E. Canada further explores the moral distress and burnout that occurs when students in health professions are faced with this lack of parity when working in free clinics and community health clinics geared toward the undocumented and proposes ways to mitigate this distress.

The sheer range of obstacles that immigrants must overcome to attain health care and the subsequent disparity in quality and quantity of care they are able to receive can feel daunting to physicians who wish to care for and advocate for them. Often clinicians’ day-to-day work involves finagling workarounds, that is, finding ways to deliver care even in systems not designed to serve patients. Nancy Berlinger comments on the ethical and logistical challenges that can arise when physicians are compelled to improvise to deliver routine care. Mark G. Kuczewski, Johana Mejias-Beck, and Amy Blair discuss how training physicians to deliver care that is informed by a patient’s legal status is integral to the quality of care delivered, and they suggest materials and resources to help open up this line of dialogue between physicians and their patients.

On a larger scale, several articles in this issue discuss policies on national and state levels that affect the health care that undocumented immigrants receive. Berlinger and Rachel L. Zacharias provide a practical overview of the effects of immigration policy and enforcement on health care access. In particular, documentation of a patient’s immigration status in electronic health records is controversial. Grace Kim, Uriel Sanchez Molina, and Altaf Saadi explore the risks to privacy and confidentiality that undocumented patients undergo when entering health care spaces and provide alternatives for clinicians to documenting immigration status in electronic health records. And Scott J. Schweikart argues that immigration status could potentially be considered protected health information under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule.

The current political climate has also wrought another series of changes—recipients of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status, empowered by education and opportunity, are advocating for their communities. Medical schools have shown increased interest not only in training DACA recipients but also in teaching all students how to advocate for patients outside the wards and exam rooms. As “DACA-mented” medical students become physicians and begin to occupy leadership roles in medicine, it is without a doubt that they will work to elevate their patients out of the shadows. I and Dominic Sisti discuss ethical issues that arise when “DACA-mented” clinicians disclose their own immigration status to their patients and also shed light on the challenges that these clinicians face in their training, including the need for added emotional and legal support from their institutions.

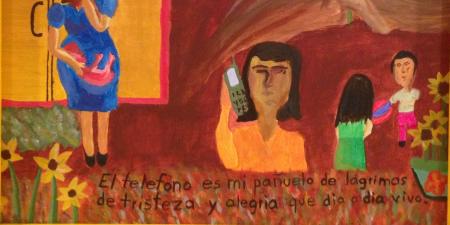

In addition to the detrimental effects on DACA recipients, the current administration’s immigration policy has impacted the health of children. Craig B. Mousin writes about the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), a series of policies adopted by the United Nations in 1989 that recognized children’s rights. Mousin discusses the ethical and health implications of the United States’ failure to adopt the CRC, especially for immigrant and refugee children, as this past year, the United States government separated thousands of children from their families at the border with Mexico and placed many of these children in detention centers.8 Schweikart discusses a lawsuit filed in April 2018, under the Flores Settlement Agreement, alleging that psychotropic medications were being given to detained immigrant children in order to control them and prolong their detention, raising significant ethical questions. And Nora Hiriart Litz and I highlight the ways in which immigrant children’s artwork expresses their experiences of migration, family, love, loss, and hope. Finally, Rohail Kumar’s storybook on the life of a composite fictional character portrays how family separation deprives undocumented children of food, health care, and schooling.

The health of our immigrant populations is at risk, and it is imperative that physicians are informed about the issues that affect these populations and are equipped to act as effective advocates. Advocacy should begin in medical school where social determinants of health are dissected alongside cadavers, in resident clinic exam rooms where culturally competent care is modelled, in health disparities research institutes, and in social media campaigns where physicians lead the call to action. This issue of the AMA Journal of Ethics hopes to begin conversations about the challenges physicians face in caring for our millions of undocumented immigrants and to empower individual clinicians to be part of the solution.

References

-

Baker B. Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2014. US Department of Homeland Security. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Unauthorized%20Immigrant%20Population%20Estimates%20in%20the%20US%20January%202014_1.pdf. Published July 2017. Accessed October 18, 2018.

-

Parmet WE. Immigration and health care under the Trump administration. Health Affairs. January 18, 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180105.259433/full/. Accessed November 9, 2018.

-

National Immigration Law Center. Immigrants and the Affordable Care Act (ACA). https://www.nilc.org/issues/health-care/immigrantshcr/. Revised January 2014. Accessed October 18, 2018.

-

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, Pub L No. 104-193, 110 Stat 2105.

- Kaushal N, Kaestner R. Welfare reform and health insurance of immigrants. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(3):697-722.

-

Berlinger N, Gusmano M. Healthcare access for undocumented immigrants under the Trump Administration. Hastings Bioethics Forum. December 19, 2016. https://www.thehastingscenter.org/health-care-access-undocumented-immigrants-trump-administration/. Accessed October 18, 2018.

-

Watson T. Inside the refrigerator: immigration enforcement and chilling effects in Medicaid participation. https://www.nber.org/papers/w16278.pdf. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 16278. Published August 2010. Accessed July 12, 2018.

-

UN News. UN rights chief slams “unconscionable” US border policy of separating migrant children from parents. https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/06/1012382. Published June 18, 2018. Accessed June 18, 2018.