Abstract

Health equity is a common theme discussed in health professions schools, yet many educators are wary of addressing it. Avoidance of health equity content in health professions education leads to student frustration and missed opportunities to educate the next generation of health care professionals about sensitive yet important issues. Moreover, this gap in students’ knowledge can negatively influence patients and perpetuate disparities.

Lack of Health Equity Training

Medical education constantly evolves to accommodate scientific advances, new practices, and modifications to the existing medical curricula. Core competencies and system-based learning are traditional mainstays that prepare students for standardized board exams (the United States Medical Licensing Examination® Step 1 and 2). However, content on health disparities (commonly referred to now as health inequity) does not fit perfectly into established medical education silos. Educators in medical and in all health professions schools craft their core content to ensure that learning objectives are met and that students have the knowledge to advance to their next stage of training. Given limitations on curricular time, perceptions that health equity education is less necessary or less important, or educators’ lack of knowledge of inequities’ downstream impact, health equity is often underemphasized or absent in core curricula despite the fact that 50% of an individual’s overall health is influenced by socioeconomic and environmental factors.1

The Association of American Medical Colleges recommends that medical educators expose their students to health disparities content.2 Yet the recommendations concerning format, delivery, and requisite degree of competency are ill-defined. Furthermore, the integration of this material varies by institution. In the medical community, factors that might contribute to its poor adoption include educators’ limited expertise, overall discomfort in facilitating discussions on health equity, or fear of unintentionally offending groups by using incorrect terms or making incorrect assumptions or of provoking backlash.

Health Equity Matters

Various studies have highlighted the downstream consequences of clinicians’ implicit bias on patients’ adherence, follow-up, and trust, which has led to development of implicit bias training for health care professionals.3 Lack of trust reduces patient satisfaction, which is correlated with patient-clinician racial concordance.4 Furthermore, the US patient population has become more diverse over the past 50 years and thus requires a culturally competent clinician workforce.

As medical knowledge increases, health professions educators have responsibilities to teach a diversity of public health topics that affect patient care and health outcomes. Accordingly, they must acknowledge that health equity education is integral to medical education and that these concepts must be reinforced both in the classroom and at the bedside. Thorough contextual understanding of health disparities is part and parcel of any discussion of health equity. By definition, health disparities are preventable differences in socially disadvantaged populations’ burden of disease, injury, or violence or in their opportunities to achieve optimal health.5 Some reasons why health inequity exists include individual and systemic bias and disadvantaged groups’ historical mistrust of clinicians or the health care system and low health literacy. Whenever health risk, disease burden, or disease management is discussed, health equity must be integrated into that dialogue. By describing social determinants of health, educators help students consider health care in an equity-informed way.

Recommendations for Faculty

Provide adequate cultural context beyond case-based learning. Educators often teach the epidemiology and medical management of acute and chronic conditions without identifying culture-specific anchor points. For example, students might learn the pathophysiology of syphilis without a discussion of the US Public Health Service Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.6 Similarly, students might be educated about differences in polio vaccines and cell cloning without an appropriate conversation about Henrietta Lacks.7 Both examples lend context to medical mistrust, a social determinant of health. Moreover, research demonstrates that social determinants modify disease risk.8 For example, hypertension management can be greatly affected by access to care, health literacy, and insurance status; students should be aware of how these factors influence health outcomes related to hypertension. Furthermore, awareness of social determinants challenges learners to think about the complete patient rather than isolated medical ailments.

Discuss how systemic racism and bias may result in health disparities. Educators commonly mention race/ethnicity as a risk factor for a disease. For example, race/ethnicity can be used to refer to ancestral groups or tight-knit communities where disease patterns are commonly seen as inherited. However, disease risk can be wrongly attributed to race, an example of which is hypertension. Current evidence does not support that Black people are genetically predisposed to increased risk of hypertension. Genetic research has not identified a single variant or polygenic pattern that explains the disproportionate burden of hypertension in Black people.9 However, studies have shown that African Americans report higher stress levels due to perceived racial discrimination, which is associated with hypertension.10 Distinguishing between health outcomes related to genetics and social determinants is a critical skill to which medical students should be exposed. A position of equity would acknowledge that race is a social construct and that therefore racism—not race—contributes to health disparities between certain groups.

Discuss the demographics table in research. In sharing evidence from clinical research, it is essential to (1) highlight diversity in the populations studied and (2) explore how that diversity, or lack thereof, affects the quality of the study. The effects of diversity are increasingly being seen in genomics research.11 For example, in the hallmark development of a warfarin dosing algorithm based on select gene variants involved in metabolism,12 the underrepresentation of African Americans in the research resulted in the absence of important metabolism-altering variants prevalent in that population. Consequently, the algorithm had lower therapeutic utility in African Americans.13 Educators can address students’ concerns regarding the validity of findings as applied to patients whose data are missing from the original research. Doing so aids students in developing a strong understanding of social determinants of health as they pertain to evidence-based practices.

Practice inclusion. Practice inclusion by providing diverse visual examples in case-based learning. When teaching about conditions involving patients’ phenotypes (appearances), it is important to show a range of patients and cases. For example, a 2006 review found that many dermatology textbooks lack representation of darker skin complexions.14 Inability to recognize rashes as early Lyme disease in Black patients, for example, results in diagnosis and treatment delays for these patients.15 Additionally, when inviting patients into a classroom to discuss their disease, invite patients from diverse backgrounds. Social and cultural experiences uniquely influence the patient experience and can affect disease course, so a plurality of perspectives should be represented in patients seen in the classroom.

A position of equity would acknowledge that race is a social construct and that therefore racism—not race—contributes to health disparities between certain groups.

Differentiate the facts from the myths. It is necessary to clearly delineate empirical evidence related to racial/ethnic factors from medical hearsay. Misinformation can compound negative stereotypes and worsen the effects of implicit bias. For example, a 2016 study revealed that students and trainees both endorsed the false belief that Black patients had higher thresholds for pain and thicker skin than other ethnic groups.16 Misconceptions like these legitimize undermanagement of pain symptoms in Black patients.17 The hierarchical structure of health professions education discourages students and trainees from openly challenging inaccurate information. In teaching health equity to students, educators must call out the myths, discuss their origins, and supplant them with evidence.

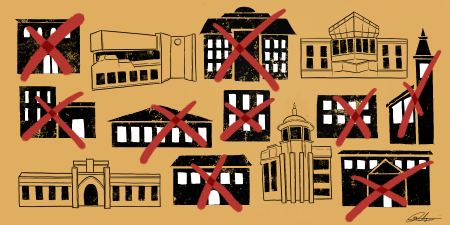

Eliminate stand-alone lectures on health equity. Integrate health equity content longitudinally and in relation to other topics. For example, consider maternal mortality. Although epidemiology is typically shared in maternal health content lectures, the underlying factors that increase the risk of maternal death among Black women compared to White women might not be mentioned and instead be left for a separate discussion on health inequity. Lack of content integration further distances clinicians from underlying social contexts that affect patients’ health status. An overarching goal should be to eliminate views of health equity and medicine as separate.

Consider roles that current events and popular culture play in understanding of diverse patients. Cultural exposures to and lived experiences of people from diverse groups offer insight that can guide clinical management. Knowledge of relevant cultural tropes or memes aids in establishing rapport with patients and builds context for understanding their clinical concerns. In one such case, knowledge of the musical catalogue of a popular entertainer helped a clinician realize a Latino teenage patient’s suicidality.18 Furthermore, clinicians’ knowledge of a patient’s cultural interests can be perceived as affirming. Students should be made aware of the interplay among culture, disease prevalence, disease management, and adherence.

Recommendations for Administrators

Promote diversity of educators and course leadership. It is important to ensure that students learn from a diverse group of educators. Faculty members from a background underrepresented in medicine can introduce different perspectives and methods of teaching. Faculty members who have practiced in different settings (including nonacademic environments) might be able to provide insight into authentic patient interactions and unique career experiences. Both sources of diversity can aid learners or amplify relevant teaching points. Studies support that students trained at schools with a diverse student body are more comfortable treating patients from different racial and ethnic backgrounds.19 Leadership should actively recruit faculty members who represent the entire spectrum of cultural experiences and patient populations.

Don’t single out the minority to be the peer educator for the issue at hand. Underrepresented minorities often feel significant pressure to represent an entire community because of their position and status. Colloquially, this pressure is referred to as the minority tax, and it is often experienced by faculty, trainees, and medical students. It is an unrealistic and unfair expectation to assume that the thoughts and views of an entire racial/ethnic group can be represented by a single member. Accordingly, minority students should not be singled out, asked to speak on behalf of a given culture, asked to share their cultural experiences as a learning tool, or asked to convey opinions of an entire community.

Recommendations for Faculty and Administrators

Ask for help even if you think you’re an expert. Many clinicians have expert knowledge of disease processes, including a cursory understanding of related social determinants. But health equity is dynamic—there is a continuous influx of new information and data available to help clinicians address and eliminate inequity in health care. Realistically, no single clinician will be fully abreast of every policy change, intervention model, data set, or improvement in health equity. To fill knowledge gaps, identify and engage health equity experts that are outside of your particular health field or specialty; candidly ask for advice on methods of teaching health equity topics to student audiences.

Lean in. Don’t avoid the issue. The students want this content. More importantly, patients will benefit. Health equity has tremendous breadth and reach, and in recent years it has moved beyond being a buzzword. Students are actively invested in social medicine, global medicine, and health policy; the expectation is that their instructors are versed in this material and can make the link between these topics and medical pathology. Consider each lecture, group discussion, and bedside teaching moment as an opportunity to “lean in” to health equity. Students will naturally follow and, in the process, conversations about health determinants will become normalized.

Conclusion

In summary, health equity is a vital, underemphasized component of health professions education. As our country continues to diversify, educators’ approaches to teaching must accommodate diversity in thought, practice, and experience. The benefits of inclusiveness also apply to curricular content. Retrofitting core curricula with health equity content should be championed by educators of all racial/ethnic backgrounds. Motivating incremental changes in teaching methods and working consciously to integrate health equity into clinic- and classroom-based environments are next steps.

References

- Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County Health Rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):129-135.

-

Association of American Medical Colleges. Quality improvement and patient safety competencies across the learning continuum. New and Emerging Areas in Medicine Series. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019. Accessed January 23, 2021. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/302/

- Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504-1510.

- Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997-1004.

-

Health disparities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed January 31, 2020. Accessed May 28, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/disparities/index.htm

-

Stein R. Troubling history in medical research still fresh for Black Americans. NPR. October 25, 2017. Accessed July 25, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/10/25/556673640/scientists-work-to-overcome-legacy-of-tuskegee-study-henrietta-lacks

-

Skloot R. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Broadway Books/Random House; 2010.

-

Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 10, 2018. Accessed July 25, 2020. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/

-

Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Stroke Council. Cardiovascular health in African Americans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(21):e393-e423.

- Brondolo E, Love EE, Pencille M, Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G. Racism and hypertension: a review of the empirical evidence and implications for clinical practice. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(5):518-529.

- Landry LG, Ali N, Williams DR, Rehm HL, Bonham VL. Lack of diversity in genomic databases is a barrier to translating precision medicine research into practice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(5):780-785.

-

Klein TE, Altman RB, Eriksson N, et al; International Warfarin Pharmacogenetics Consortium. Estimation of the warfarin dose with clinical and pharmacogenetic data. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):753-764.

- Drozda K, Wong S, Patel SR, et al. Poor warfarin dose prediction with pharmacogenetic algorithms that exclude genotypes important for African Americans. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2015;25(2):73-81.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):687-690.

- Fix AD, Peña CA, Strickland GT. Racial differences in reported Lyme disease incidence. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(8):756-759.

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(16):4296-4301.

- Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150-174.

-

Brown I. How Uzi Vert is changing mental health for millennials. Medium. June 19, 2018. Accessed January 23, 2021. https://medium.com/@italobrown/uzivertmentalhealth-fe2886af6b98

- Whitla DK, Orfield G, Silen W, Teperow C, Howard C, Reede J. Educational benefits of diversity in medical school: a survey of students. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):460-466.