Abstract

Art Rounds is an interprofessional workshop that uses art to develop nursing and medical students’ observation skills and empathy. The workshop’s joint emphasis on interprofessional education (IPE) and visual thinking strategies (VTS) is intended to improve patient outcomes, strengthen interprofessional collaboration, and maintain a climate of mutual respect and shared values. Interprofessional teams of 4 to 5 students practice faculty-guided VTS on artworks. Students then apply VTS and IPE competencies in observing, interviewing, and assessing evidence during 2 encounters with standardized patients (SPs). Students also write a chart note that includes differential diagnoses with supportive evidence for each of the 2 SPs. Art Rounds focuses on students’ observation of details and interpretation of images and SPs’ physical appearance; evaluation strategies include grading rubrics for the chart notes and a student-completed evaluation survey.

Integrating Arts Into Interprofessional Education

The World Health Organization (WHO) and Institute of Medicine (IOM, now the National Academy of Medicine) explicitly recommend interprofessional health care teams as a strategy to enhance communication and care coordination and to improve health services and patient health outcomes.1,2 The mission of the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) is to ensure that new and current health care professionals are proficient in the competencies essential for interprofessional, collaborative practice.3 Some health professions programs in dentistry, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and public health mandate IPE in their curricula and incorporate IPEC core competencies in their training model.3,4

Clinical observation and empathetic communication are crucial and fundamental skills for all health care clinicians, regardless of discipline. Oversights in history taking, physical assessment, and communication can lead to delayed or inaccurate diagnoses, unnecessary medical testing, higher medical costs, misunderstanding of patient needs, or disparities and severe adverse outcomes for patients.5 To improve skills in these areas, visual art education has been used. Contemplation of artworks not only improves observational skills but also forces viewers to “hear and see” from another’s perspective. Visual art education thus can be a tool to enhance mutual understanding among members of an interprofessional team as well as among clinicians and patients. For example, Wikström found that visual arts dialogues helped nursing students develop sensitivity to others that is central to nursing situations.6 Visual arts training has also been shown to improve observation skills and to cultivate empathy.7,8

This article describes an interprofessional education (IPE) workshop, Art Rounds, which is the first component of a longitudinal IPE curriculum for learners in preclinical health care. The curriculum takes a learner-centered approach, whereby instructors provide a social environment for interactive and adaptive learning,9 facilitating and guiding students through a learning process that centers on Art Round activities that simulate real-world work done in the health care industry. This learning involves team projects with hands-on application activities in the domains of observation, communication, history taking, and patient care. The overarching goal of this 1-year curriculum is to stimulate dialogue and discussion, develop tolerance for ambiguity, and improve physical observation skills and history taking among health care learners from different disciplines.

Course Design

First-year medical and first-semester undergraduate nursing students are assigned to multidisciplinary student teams for the workshop before it even begins. As a preworkshop assignment, all students receive a link to view a video titled “Learning Together to Practice Collaboratively: Key Principles for Interprofessional Education” to introduce the concept of interprofessional education.”10 Additional preparation work includes instructing students to read the IPEC IPE core competencies, a link to which was provided.3 Students then participate in a 3-part IPE activity focused on observation, communication, and assessment.

Observation. In part 1, the IPE student teams are led through observation exercises using visual artworks in which they learn about visual thinking strategies (VTS)11,12 in a 2-hour session. Facilitators are guided by the questions: What do you see? What do you see that makes you think that? What more do you see? The goal is to teach the students to observe, gather assessment information or supporting evidence, and then provide a conclusion for their observation. The art professor first facilitates students’ application of the VTS strategy to “diagnose” a set of artworks in their interprofessional teams. Then medical clinical faculty facilitates applying VTS to another set of artworks. For each artwork, students are given 2 to 3 minutes to observe and discuss the artwork with their teammates, and later they report back to the group. The figure below is an example of an artwork used in the workshop.

Figure. Wind From the Sea, 1947, by Andrew Wyeth

Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Media

Tempera on hardboard, 47 cm × 70 cm.

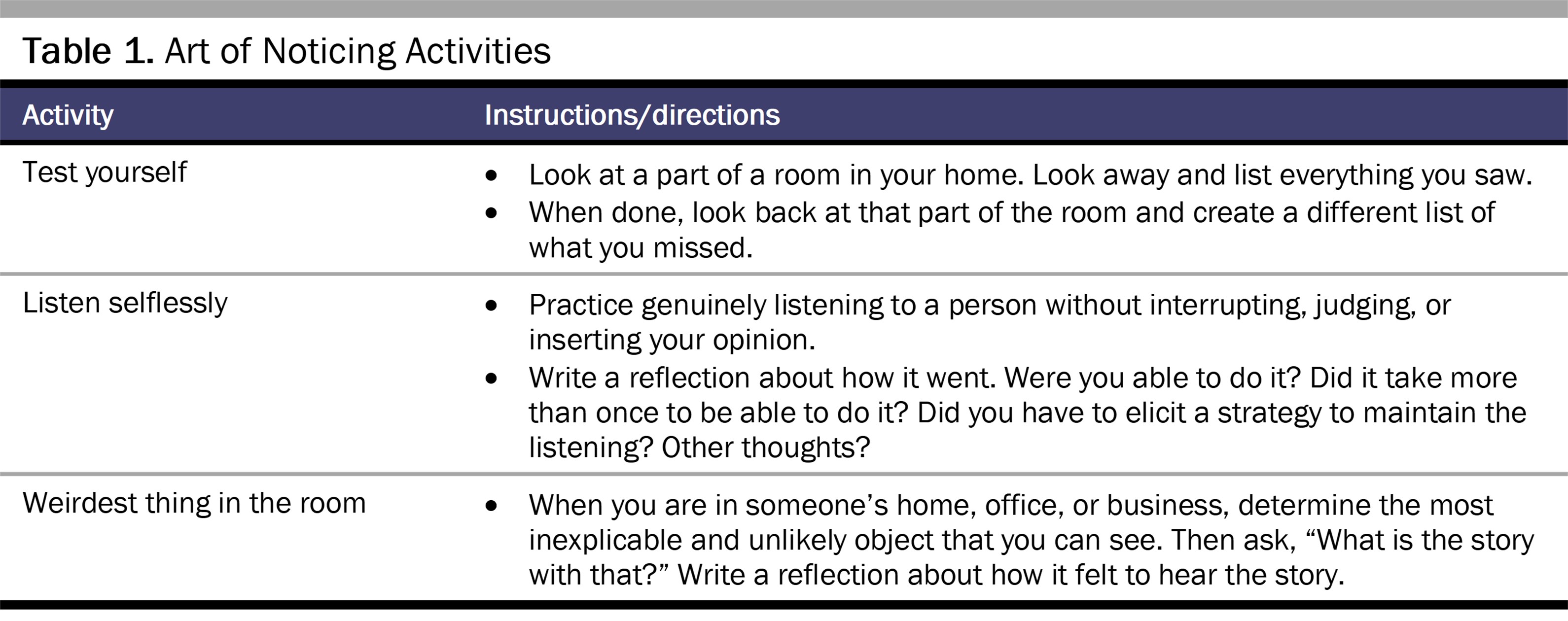

Communication. To improve their communication as well as observation skills, in part 2, students participate in an out-of-class activity based on Rob Walker’s book, The Art of Noticing: 131 Ways to Spark Creativity, Find Inspiration, and Discover Joy in the Everyday.12 The book offers exercises that assist the reader in thinking more clearly, listening better, and observing without bias. Students are asked to choose 1 of 3 exercises on the “art of noticing” (see Table 1), complete the exercise using VTS, and write up their exercise results explaining how VTS were applied. Students then share their experience of completing the exercise with other members of their student team as preparation for part 3 of Art Rounds (simulation session).

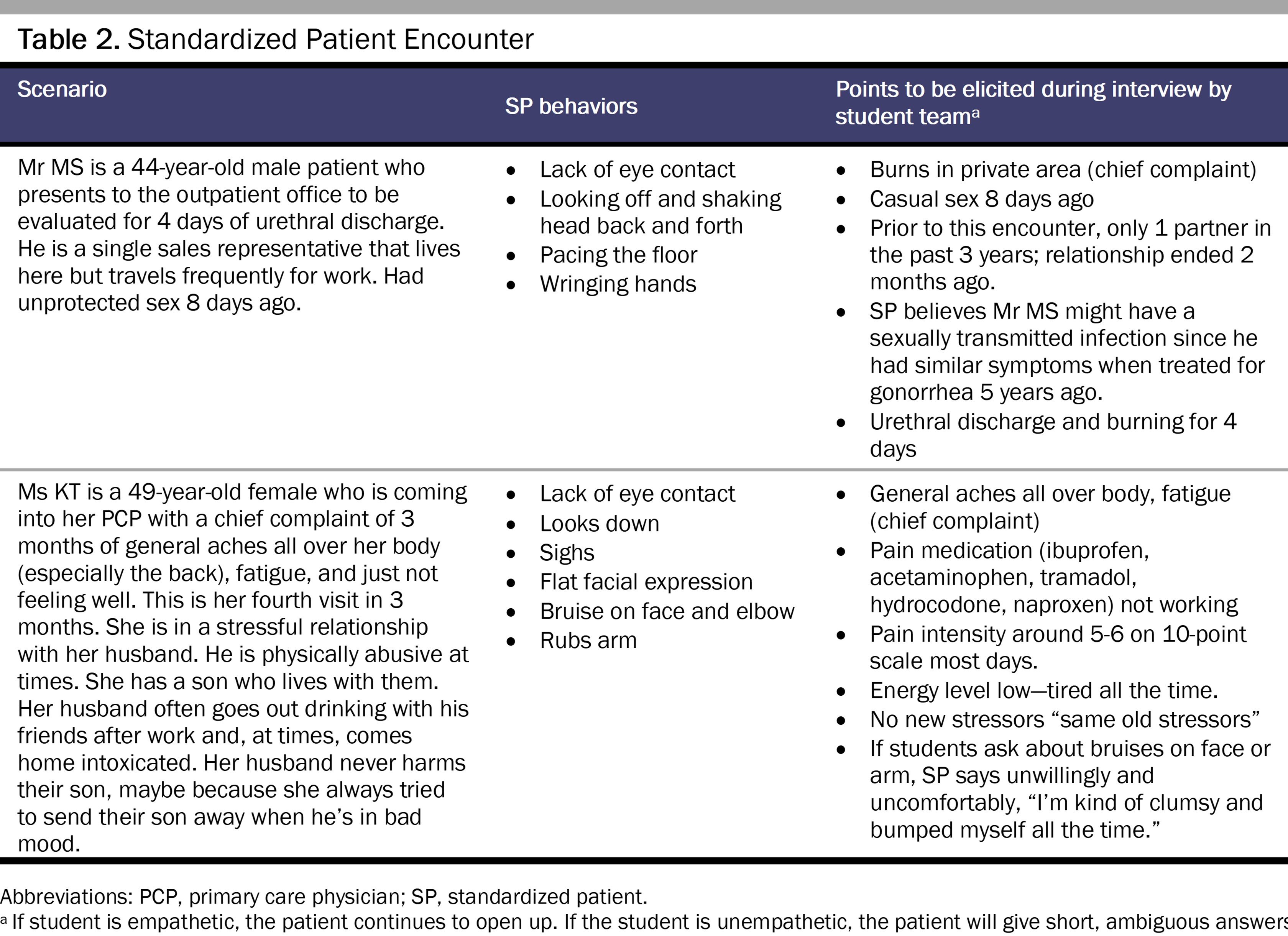

Assessment. In a 4-hour simulation session, IPE student teams apply VTS to solve simulated patient cases. Standardized patients (SPs) trained to present a clinical problem to student teams demonstrate certain nonverbal behaviors, such as pacing, hand wringing, and not making eye contact (see Table 2). Before starting the history taking process, each student team has 5 minutes to discuss how to interview the SP based on 3 minutes’ observation in the patient room. The student teams then have 12 to 15 minutes to establish rapport with the patient, obtain a detailed history relevant to the chief complaint, and obtain a pertinent review of systems. After the interview, the student teams receive 5 minutes of feedback from the SP on how the team made them feel during the interview and on team dynamics.

Student teams also write a medical care note that includes at least 3 differential diagnoses for the SP listed in order of likelihood (most to least). For each diagnosis, the student team provides an explanation and supporting evidence based on their observation of and interview with the SP. Faculty grade the note on a simple 1 to 4 scale. Each team is expected to identify the priority differential diagnoses for each SP (intimate partner violence and sexually transmitted infection) to get the 2 priority diagnosis points. Student teams can gain 2 additional points by listing the supporting data they obtained that justify the differential diagnoses.

Workshop Evaluation

During the academic year 2020-2021, the workshop evaluation was based on a total of 192 preclinical students from medicine, nursing, and pharmacy who worked in teams of 4 to 5 students.

Assessment exercise. The benchmark is that 70% of the teams will score at least 75% or that 3 of 4 criteria will be met. A total of 16 student teams (76%) scored at least 3 out of 4, thus meeting the benchmark.

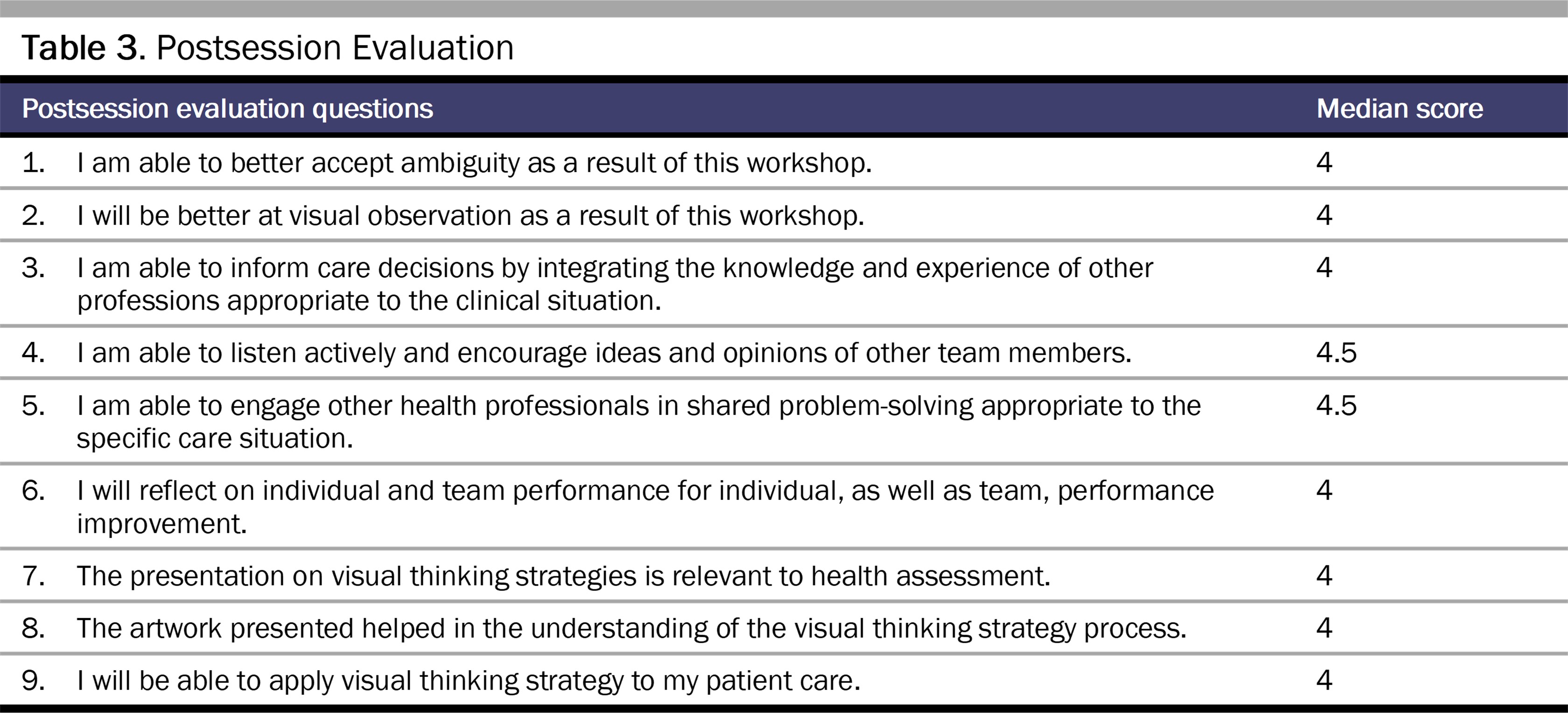

Self-report of IPE competency objectives. On a workshop evaluation questionnaire, students rated their level of agreement with meeting workshop and IPE competency objectives using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree. Table 3 displays median scores for the 9 questions.

On the evaluation, the students were also given the opportunity to comment on the artwork and presentation, any experience they have with art, and the workshop in general. The majority of comments were positive, and many students stated that their observational skills had improved. In addition, it appears that students appreciated the artworks and VTS exercise. (“The artwork allowed us to be better observers,” “I liked that the pieces were medically relevant. The artwork was very nice and had many hidden details that aide in health assessment.”) However, some had difficulty relating it to patient care. (“I don’t believe viewing art was at all helpful in being more observational with patients.”) They also highly valued the standardized patient experience. (“Simply give more patient scenarios like day 2 simulation patients.”) The IPE aspect of the activity is also captured in student comments, such as “It was nice and informative to work with students of other disciplines” and “This was a very fun activity and I enjoyed collaborating with the medical students.”

Conclusion

Health professions educational curricula set forth the expectations of empathetic communication, comprehensive observation, ethical collaboration, and clinical skills development with the goal of ensuring competency in history taking in a patient encounter. We believe that when students from different fields are provided with opportunities to learn together and from each other, they will be better prepared to collaborate in the future and to address highly complex health care issues found in workplaces. Students participating in a multisession Art Rounds were able to develop a foundational level of these skills. Art Rounds provided multiple opportunities for the same student teams to work together, engage in dialogue, and learn about patient care. By combining artwork and standardized patient encounters, students learn how to observe details and interpret images and physical appearance based on available evidence. We anticipate that additional IPE activities included in the longitudinal curriculum will further develop and solidify these skills. Our future plan is to build on Art Rounds by including additional medicine-related artworks and using a more lifelike service-learning IPE model.

References

-

Health Professions Network Nursing and Midwifery Office, Department of Human Resources for Health. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. World Health Organization; 2010. Accessed October 25, 2022. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70185/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf?sequence=1

-

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy Press; 2001.

-

Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2016. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2016-Update.pdf

-

Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education. Standards for accreditation of baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs. Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education; 2018. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/CCNE/PDF/Standards-Final-2018.pdf

-

Faustinella F. The power of observation in clinical medicine. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:250-251.

- Wikström B. Works of art: a complement to theoretical knowledge when teaching nursing care. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(1):25-32.

- Gurwin J, Revere KE, Niepold S, et al. A randomized controlled study of art observation training to improve medical student ophthalmology skills. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(1):8-14.

- Shapiro J, Rucker L, Beck J. Training the clinical eye and mind; using the arts to develop medical students’ observational and pattern recognition skills. Med Educ. 2006;40(3):263-268.

- Bada SO. Constructivism learning theory: a paradigm for teaching and learning. IOSR J Res Educ. 2015;5(6):66-70.

-

Gilbert JHV. Learning to practice collaboratively: key principles for interprofessional education. Ontario Tech University Teaching and Learning Centre. January 23, 2012. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yquPOh1SpIc

-

Visual Thinking Strategies. Accessed May 2022. https://vtshome.org/

-

Walker R. The Art of Noticing: 131 Ways to Spark Creativity, Find Inspiration, and Discover Joy in the Everyday. Knopf; 2019.