Case

Dr. Brooks completed a routine breast exam on Ms Civali and found a suspicious mass. After running necessary tests, Dr. Brooks discovered that Renee Civali has early stage breast cancer. Ms Civali is a 40-year-old, petite woman who is single and works as a successful car salesperson. Ms Civali has been seeing Dr. Brooks for the past 5 years, and chart notes indicate that Ms Civali has been occasionally emotionally unstable and has made most decisions based on what others tell her to do.

Following the diagnosis of breast cancer, Dr. Brooks explained to Ms Civali that she had 2 main treatment options: a total mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery, both options followed by chemotherapy and radiation. Dr. Brooks told Ms Civali that both treatment plans would most likely rid her body of the cancer, but each would carry a specific consequence. Ms Civali, admittedly overwhelmed and unsure of what decision to make, asked Dr. Brooks to make a therapeutic decision on her behalf. Dr. Brooks ultimately suggested the breast conserving surgery and justified the decision by reasoning that this was a less intrusive method with lower chances for a loss of body image, self-esteem, and other psychological issues that often affect younger women with this type cancer. Dr. Brooks believed that, if followed by chemotherapy and radiation, the less radical surgery would achieve the same medical results as the more radical total mastectomy.

Several months after the surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation treatments—all of which appear to have been successful—Dr. Brooks raises the possibility of Ms Civali's beginning an orally administered hormone-based therapy, telling Ms Civali that this could help reduce the risk of the cancer's recurring. Dr. Brooks however, admits to Ms Civali that research suggests that many women may not actually need the hormonal treatment in order to remain in remission because their initial surgery coupled with the follow-up therapies were sufficient. Dr. Brooks explains the various side effects of a hormone-based regimen and states that some women find that the potential benefit is not worth the distressing side effects when there are no signs of aggressive disease. After listening to this proposal, Ms Civali discloses her feelings of depression about the status of her disease and questions whether or not the partial mastectomy was most effective in eliminating her cancer. Ms Civali also acknowledges significant frustration with her current medical situation, saying she feels worn down by the constant trips to the hospital and other reminders of her recent medical history and wishes that she could return to the life she led prior to the discovery of her cancer. After hearing Dr. Brooks discuss the next possible round of treatment and expressing her concerns—both physical and psychological—Ms Civali reports that she is unwilling to make an independent decision with regard to the hormone treatment and asks Dr. Brooks for her recommendation.

Commentary 2

The case of Ms Civali evokes questions that physicians need to reflect on when dealing with early stage breast cancer and its potential psychosocial implications.

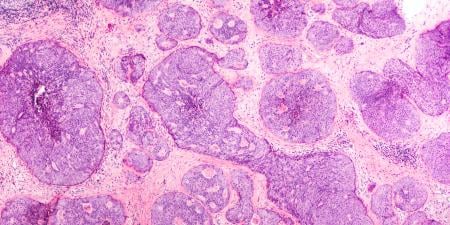

Initially, the physician has to give priority to providing sound medical advice and counseling. This clinical step should always be based on a risk-benefit assessment, which requires a complete and detailed medical characterisation of the respective cancer: one would like to know, for example, the localisation, histology, TNM staging, grading, hormone-receptor status (ER, PR), and additional risk factors, at least the HER2/neu overexpression. Primary treatment of localized breast cancer, which is what Ms Civali has, consists, in most cases, of breast-conserving surgery, followed by radiation and systemic adjuvant therapy according to the particular risks of the cancer. In this case these prognostic and predictive factors are unknown, but it may be assumed that Dr. Brooks' decision to perform a breast-conserving surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiation was the most appropriate first step of Ms Civali's cancer treatment.

Now the next treatment questions are: why was hormone treatment not suggested earlier, and should the physician recommend Ms Civali start the hormone treatment several months after completing chemotherapy and radiation? With respect to medical facts, Dr. Brooks' proposal of a hormone therapy allows us to conclude that the carcinoma cells are receptor-positive. The benefit of hormone therapy is about 5–10 percent reduction in the 10 year mortality rate. Although Tamoxifen—the most popular hormone treatment drug—is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism and endometrial cancer, the statistical gain is widely believed to greatly outweigh the medical risks. Thus, based on statistical and diagnostic trends, Dr. Brooks is justified in recommending the hormone treatment. Recent data suggest using Anastrozole instead of Tamoxifen as the preferred treatment, because it significantly prolonges disease-free survival and has fewer side-effects.1

A physician's advice should not be based solely on general statistical outcomes, but should always include a personalized risk-benefit assessment that takes into account the unique circumstances of the individual patient. Clear and sensitive communication about the anticipated long-term outcomes and acute effects must be discussed openly and within the context of the patient's life. In this case, Ms Civali feels unable to make an independent, personal decision and asks Dr. Brooks for a recommendation. This situation is an analogue to the earlier instance in which Ms CiIvali asked Dr. Brooks to decide whether or not she should have breast surgery. When considering her unwillingness to actively participate in the decision making process, it is important to recognize that Ms Civali's attitude indicates early symptoms of clinical depression. These symptoms require specific medical treatment and psychological support.

So how should Dr. Brooks advise Ms Civali about the adjuvant therapy? Adjuvant therapies are often thought to present considerable restrictions on patients' quality of life. Thus, 2 criteria of medical decision making compete with each other: general statistical benefit has to be weighed against possible changes in individual quality of life. The basis for assessing the patient's quality of life is the patient's subjective evaluation of her own condition. These subjective perceptions cannot be derived authentically from the outside. They depend on personal values and moral principles that reflect the very individual experiences and understandings each person has had in her or his life. If, for example, a patient who has a chronic disease and has received extensive medical treatments views taking drugs and making regular visits to the hospital as a significant burden, this presents a serious and important decision making consideration for the consulting physician. Sometimes fatigue, frustration with the medical situation, and the need for prolonged inpatient hospital care, may justify a decision to forgo specific forms of treatment. Here, Ms Civali is obviously frustrated with her current situation. She feels worn down by the constant trips to the hospital and wishes to return to the life she led before her cancer was detected. So should Dr. Brooks not recommend hormone therapy to Ms Civali in light of her individual psychosocial situation and the fact that there are currently no signs of cancer in her body?

This scenario also has to take into account the possibility that Ms Civali may just be temporarily overwhelmed by emotions related to her medical condition and treatment. These reactions may pass after a short time when the patient has gained some rational, reflective distance on her situation. Therefore it seems to be important to rule out true depression as well as a temporary emotional state that may unduly influence her quality-of-life assessment. In such fragile situations it is not only the right of the patient to waive the active role in decision making, it may even be wise to do so by asking the physician for advice, as Ms Civali has done—especially when the physician appears to have led the decision-making process very responsibly. Although time is scarce in everyday clinical life, good quality care and empathy require the doctor to find out about patients' preferences and wishes and to disclose potential agonizing symptoms and side effects of treatment options. As physicians, we need this kind of normative and psychosocial cooperation from the patient in order to reach a patient-centered treatment decision.

The alternatives to adjuvant hormone treatment should also be openly discussed with the patient. In the case of Ms Civiali one of the alternatives is no further treatment at all. But would the denial of hormone treatment allow her to live a "normal life" again, ie, the life she led prior to the discovery of her cancer? Although Ms Civali hopes so, cancer patients usually do not forget the disease and their changed status of life simply by avoiding the hospital. The anxiety of cancer recurrences or possibly undetected metastases remains. Some periodical follow-up is usually requested by the patients to confirm the remission of the cancer. Hence, the hope of Ms Civali to escape her disease merely by rejecting a hormone treatment seems to be illusionary. Nevertheless, if her fatigue of treatment is so strong that she wants to avoid any more external medical reminders of her disease, Dr. Brooks should accept these feelings while assuring her that she is welcomed whenever she feels the need to communicate with or be seen by a doctor.

If I were in Dr. Brooks' place, I would try to make Ms Civali aware of her particular risk-benefit ratio, including the statistical advantages of adjuvant therapy. Assuming a hormone-receptor-positive tumour and considering the given psychosocial facts, the justification for a hormone treatment seems preponderant. Anastrozole (or Tamoxifen) is usually well-tolerated, and its benefits will almost certainly outweigh its potential side effects (eg, hot flashes and vaginal discharge). These side effects are rather mild given that the patient has already tolerated the much harsher side effects of chemotherapy. If the assumption that the benefits will outweigh the individual side effects turns out to be wrong in Ms Civali's case, it is still possible to either modify or discontinue the treatment after evaluating the regimen together with the patient.

In conclusion, I would recommend the hormone treatment to Ms Civali, but acknowledge her concerns by accompanying the treatment with psychological support, specifically a program to enhance self-esteem and to provide all possible help for reintegration in her life and work. As argued above, communication between patient and physician remains the most important guide to achieving shared decision making which depends heavily on excellent medical information and the personal risk-benefit assessment. The latter is usually best expressed by the patient, who is the only one in a position to make the individual risk-benefit assessment since this has to be done according to her very own way of living, her experiences, and her preferences.

References

- Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):60-62.