Case

John is on his family practice rotation and working at an outpatient clinic. One day he sees Ms Smith for a routine medical exam. She has been a patient of the clinic for 7 years, has always been compliant with recommendations, and has no significant past medical history. While reviewing Ms Smith's history with her, John asks if she has any specific questions or concerns. Ms Smith states that she recently saw an ad about organ donation and wanted to know more about becoming a donor. John becomes excited about this question because he knows that there is a shortage of organ donors, and he sees this as an opportunity to educate Ms Smith about this altruistic act. At 30 years old and in good health, Ms Smith is probably an eligible donor, John thinks.

As the conversation progresses, Ms Smith asks John if he has "ever seen organs being removed for donation" and John states that he, personally, has not seen this, but knows that the utmost care is taken to procure the organs. Ms Smith then discloses that she is worried that if she becomes a donor her organs may be taken before she is dead. John assures Ms Smith that this would not happen and that many tests are performed to make sure the patient is dead before organs are recovered. After answering all her questions, John informs Ms Smith that she can fill out the necessary paper work for organ donation in the office. Just as he is about to excuse himself to get her the necessary documentation, Ms Smith states that she is not entirely convinced about being an organ donor. "I'm still unsure—I still need some time to think about it." John is clearly disappointed because he knows how important organ donation is but does not want to pressure Ms Smith into making a decision.

Commentary 3

This scenario in which Ms Smith consults her doctor's office about becoming an organ donor is realistic. A recent survey asked southeast Ohio residents, "Where would you prefer to get information about organ donation," and nearly 82 percent of the respondents indicated the family doctor or health care provider.1

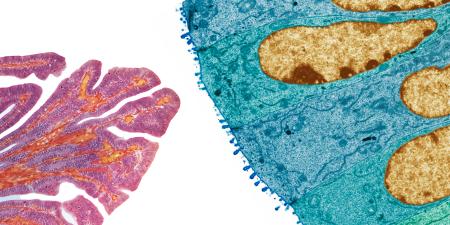

Organ and tissue donation can occur under 1 of 3 conditions: (1) death as determined by neurologic criteria (also known as "brain death"), (2) death as determined by cardiac criteria, and (3) living donation. The American College of Surgery's Code of Professional Conduct, published in 2003, delineated the primacy of patient welfare. The surgeon is primarily responsible for communicating "the therapeutic options in a fashion that is both comprehensive and comprehensible, and in a manner that is inclusive of the patient's values and belief systems."2 The American Medical Association's Code of Medical Ethics recognizes the physician's "responsibility to participate in activities contributing to the improvement of the community" as well as the need to "support access to medical care for all people."3 In order to manage the ethical demands made by these organizations, physicians must balance respect for individual patient autonomy with concern for all of society.

Each of the methods for organ and tissue donation has a distinctive informed consent process. In 2004, nearly half of all donors in the United States were living donors. Nearly 95 percent of these donated a kidney; just over 300 donated liver segments; 28 donated portions of lung, and 6 donated portions of intestine. Most living donors are family members or friends of the recipient, although altruistic donation is on the rise. Living donation entails significant medical risks, including those associated with general anesthesia and surgery, and the potential for long-term complications. Benefits for the donor include the recipient's improved quantity and quality of life and the sense of well-being engendered by personal generosity.

The choice to make a living donation must be a fully informed one and must include a medical evaluation. A potential living donor must go through an extensive process of education about the procedure, risks and possible complications, long-term outcomes, and possible alternatives, such as deciding not to donate. The medical evaluation is conducted by an independent physician who is the donor advocate and not part of the transplant surgical team. If the donor advocate is not satisfied with the medical evaluation and preparedness of the potential donor, he or she can unilaterally prevent the donation from proceeding. The psychological assessment of the potential altruistic donor is a subject of its own, generally addressed by the transplant center.

A proven way to increase organ donation from patients who die of brain injury is by "decoupling" the team that is caring for the brain-injured potential donor from the transplant team. The transplant team must have no part in declaring the death of the donor or receiving consent from the family for the donation. The local organ procurement agency, with support from local hospital personnel, provides information and obtains consent for donation. These individuals take great care to offer the possibility of donation without pressuring or coercing family members. Most states now make it possible for people to choose to become organ donors and record the choice on their drivers' licenses. This official document becomes a legal statement of that individual's wish to donate should that become possible. The act of "opting-in" to be a donor is a cogent way to communicate to family members and loved ones that the choice was made during a thoughtful, lucid moment. If the individual changes his or her mind, the decision can be rescinded at any time.

Death by cardiac criteria offers 2 opportunities for organ and tissue donation. In the most common scenario, the patient dies at home or in the hospital following cardiopulmonary arrest. Under these circumstances tissue donation may then follow. The second scenario—donation after cardiac death (DCD)—refers to donation by patients with severe brain injury—but not brain death—from whom the family has decided to withdraw support. Here, the option of donation is addressed independent of, and occurs after, the decision to withdraw support is made. Support is withdrawn in a controlled fashion in either the operating room or ICU, allowing the recovery of organs for transplantation. Tissue donation may also follow. In 2003, DCD accounted for 4 percent of deceased donors and 2 percent of all organ donors in the US.4 Prior to the development of death by neurologic criteria, all donated organs in the United States were recovered in this fashion.

Finally, death by neurologic criteria requires the irreversible cessation of all brain function. Common etiologies for cessation of brain function include stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, trauma, and prolonged hypoxia. Following declaration of death by neurologic criteria, donation of up to 8 organs and a variety of tissue is possible. Mrs. Smith's concern that her organs might be recovered prior to death is an oft-repeated misconception. Providing patients with printed material, websites, and access to the local organ procurement may alleviate fears—both spoken and unspoken.

References

-

Downing K. Lifeline of Ohio Southeast Ohio Residents 2004 Survey. Publication pending.

-

Barry L, Blair PG, Cosgrove EM, et al. One year, and counting, after publication of our ACS "Code of Professional Conduct." J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(5):736-740.

-

American Medical Association. Principles of medical ethics. Code of Medical Ethics. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2512.html. Accessed August 1, 2005.

-

US Transplant. 2004 OPTN/SRTR Annual Report. Table 1.1. Available at: www.ustransplant.org/annual_reports/2004/101_dh.pdf.