Case

Dr. Carpenter had taken care of 3-year-old Josh since he was born. One afternoon, Dr. Carpenter received a call from Josh’s parents, both of whom were successful professionals. Josh’s dad had just been diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, a degenerative, neurological disorder, and the parents wanted Josh to be tested for the disease. The genetic polymorphism for Huntington’s is autosomal dominant, so Josh had a 50-50 chance of inheriting the gene from his father, and, if he did, he would develop the disease if he lived to middle age.

After offering her condolences to Josh’s parents, Dr. Carpenter expressed what she considered to be a consensus opinion on the matter: “At present, there is no prevention, treatment, or lifestyle change that has an effect on expression of the gene. For these reasons, pediatric and genetic medicine specialty societies advise against testing children. Josh will have plenty of time to decide whether he wants to be tested once he is an adult.”

“I disagree completely,” said Josh’s mom. “If Josh grows up knowing he has this condition, he will be much better prepared to deal with it as an adult. He’ll be forming his identity over the next 18 years. Assuming he has the disease, he won’t face the trauma of having his identity and life plan change all at once.”

“But you’ll be denying him the chance to make the decision as an adult,” replied Dr. Carpenter. “Maybe he will decide not to know.”

“Isn’t that what parents do?” said Josh’s dad. “They make decisions for their children. If we take your approach, Josh may be 25 when he discovers that he wishes he knew all along whether or not he has Huntington’s. But he won’t have that option because of our decision not to test him. The choice to do nothing is still a choice, Dr. Carpenter.”

Commentary 1

Josh’s case raises several complex and important issues at the intersection of medicine, psychology, and ethics. His parents argue that it is their right to decide whether Josh should be tested, saying “Isn’t that what parents do? They make decisions for their children.” Yet, in fact, parents do not always do so. Parents do not decide, for example, how their children will vote in elections once they turn 18. So, too, in this case, this decision is one best made by offspring after they are adults.

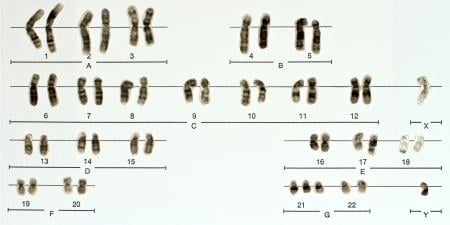

Several medical facts about the disease are highly relevant to the case. Huntington’s disease (HD) is a fatal autosomal-dominant disease with adult onset (usually when the individual is in his or her 40s or 50s) that causes several neurological and psychiatric symptoms. To date, no effective treatment exists.

Most patients have seen the devastating effects and lethality of the diagnosis in a parent. To learn that one carries the mutation can cause psychological distress and trauma, in part because there is nothing that can be done to stop or prevent the disease.

An adult may nonetheless decide to undergo testing. Such information could potentially inform decisions of whether to have children or pursue lengthy years of graduate school. Some at-risk individuals, particularly those who are health care professionals, may want to know, since they feel relatively more comfortable with such diagnoses and prognoses, having treated patients who confront these dilemmas.

Yet, not surprisingly, most at-risk individuals decide against testing. The prospect of finding out that one has an untreatable lethal mutation and having to decide whom then to tell are simply too frightening [1, 2]. Given the intensely personal nature of these preferences and decisions, standard medical practice is to recommend that individuals contemplating this decision meet with trained genetic counselors to discuss the difficult pros and cons at length.

Ethically, the principle of respect for autonomy dictates that individuals make these decisions for themselves. Thus, an adult may decide to get tested. But a parent’s right to exercise autonomy does not necessarily extend to decisions about his or her children. Arguably, a mutation-positive HD test result can harm more than help a young child. Hence, for a parent to test a child may violate principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence—i.e., benefits to an individual should be maximized, and harms minimized.

Of note here, Dr. Carpenter says that the parents would be denying Josh the opportunity to make the decision as an adult. Dr. Carpenter could perhaps have argued that the parents’ decision may in fact cause stress, anxiety, and depression for Josh. Children do not fully understand death and disease. With emotional and cognitive development, individuals gradually become better able to cope with such stresses. A child’s difficulty understanding and responding to the stresses of serious disease and death can lead to behavioral problems, and “acting out” (e.g., becoming involved in drugs).

In essence then, the critical conflict is not between the rights of the parents and the paternalism of the physician, but between the rights of the parents and the rights of the child. The parents’ decision affects a third party—Josh. Dr. Carpenter must follow the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence and decide what is best for Josh—what will potentially produce the most benefit and the least harm for him. These principles lead to a recommendation not to test Josh, which conflicts with the parents’ views of their rights to decide for him. In weighing these competing sets of principles, however, beneficence and nonmaleficence for the child outweigh the parents’ underlying claim of autonomy. From a utilitarian perspective, the overall harm of testing outweighs the potential benefit to the parties involved.

These issues might be viewed differently if key aspects of the disease were different. For example, if disease symptoms appeared in childhood and an effective treatment existed that could then be started, testing would offer clear benefits to the child, and failure to test and treat the child could in fact be harmful. Presumably in such a case, the physician would recommend testing and agree with the parents, and problems would occur if for some reason the parents opposed testing, saying that they did not want their offspring to know. Indeed, such a conflict pitching the rights of the parents against those of the child occasionally arises in the case of HIV, where late adolescents who were infected at birth need treatment, but the parents do not want to tell the adolescent that he or she has HIV in part because they feel embarrassed and ashamed at having infected the child. Many physicians believe that if the adolescent is 16 or 17 and becomes sexually active, the benefits of disclosing the diagnosis outweigh the benefits of respecting the parents’ autonomy, in part because the adolescent is more likely to transmit the virus to a sexual partner if he or she does not know about the diagnosis [3].

Similarly, if a genetic disease has adult onset, but effective treatment is available that could be advantageously started in childhood, testing would benefit the child. If effective treatment were available, physicians would recommend testing, hoping the parents would agree.

Josh’s case asks whether a doctor has a right to oppose a family’s values, but that conflict does not appear to be the critical one. Physicians have a professional responsibility to “first do no harm,” and I know of no established religious or cultural tradition that would support the parents in the present case, given the ratio of potential harm to potential benefit involved in testing the child.

Physicians can attempt to address and resolve their disagreement with the parents by discussing the issues with them and presenting the ethical arguments against testing.

At some point in the future, parents and clinicians will face dilemmas of whether to avoid these decisions altogether by using nondisclosing preimplantation genetic diagnosis. In this procedure, a physician screens embryos for HD and other mutations, and implants only mutation-negative embryos without informing the parent at risk whether any mutation-positive embryos were in fact found. In this way, a parent who is at risk (i.e., has had a parent with HD) can have a child without the mutation while avoiding having to confront the stress of knowing his or her own HD status or having to decide whether to test a child [4].

Genetic markers are being discovered for a growing number of disorders, and direct-to-consumer marketing of these tests has begun. Hence, rising numbers of patients may either ask physicians about the value of such testing or undergo testing and then ask physicians to interpret the results. Thus, physicians will need to know how to approach such complex decisions. Doctors will need to be able to offer assistance in judging the pros and cons of genetic testing to both adult patients and their offspring.

Many of these decisions raise complex challenges due to scientific uncertainties and patients’ varying psychological needs and desires. In many regards, HD is unique. Most diseases are not autosomal dominant, lethal, and without treatment. Rather, most common diseases appear to involve multiple genetic and environmental factors, and the relative contributions and roles of these genes in causing such diseases vary widely. For example, the so-called BRCA 1/2 mutations for breast cancer account for approximately 10 percent of all breast cancer, and the presence of a mutation results in disease about 40 to 60 percent of the time. Whether a patient should take this test is a highly individual and subjective decision.

Parents may want to test their children for other conditions for which tests exist, but effective treatment does not. Or a treatment may offer a small amount of possible benefit, while testing may again potentially cause some harm. Physicians then have to weigh a possible small benefit against a possible harm. These decisions entail uncertainties, subtly, and nuance, and physicians will need to feel comfortable confronting such choices.

Ideally, in all of the above genetic scenarios, doctors should refer patients to genetic counselors for assistance as needed. Unfortunately, the United States and other Western countries have severe shortages of genetic counselors. Many physicians do not know of a genetic counselor to whom they can refer patients. Thus, doctors will need to find some way to address these issues and feel comfortable doing so.

In coming years, scientific understanding of genetics will surely continue to mushroom, posing critical medical, ethical, and psychological challenges for which clinicians will need to be prepared. This preparation will help Josh, his parents, and countless others who face these conundrums.

References

- Klitzman R, Thorne D, Williamson J, Marder K. The roles of family members, health care workers, and others in decision-making processes about genetic testing among individuals at risk for Huntington Disease. Genet Med. 2007;9(6):358-371.

-

Klitzman R, Thorne D, Williamson J, Chung W, Marder K. Disclosures of Huntington disease risk within families: patterns of decision-making and implications. Am J Med Gen A. 2007;143A(16):1835-1849.

- Klitzman R, Marhefka S, Mellins C, Wiener L. Ethical issues concerning disclosures of HIV diagnoses to perinatally infected children and adolescents. J Clin Ethics. 2008;19(1):31-42.

- Klitzman R, Thorne D, Williamson J, Chung W, Marder K. Decision-making about reproductive choices among individuals at-risk for Huntington’s disease. J Genet Couns. 2007;16(3):347-362.