Abstract

This series of 5 color oil on canvas sketches includes a sequence of images and explores, from a first-person perspective, a patient’s postoperative recovery experiences.

Five color oil on canvas sketches explore my recovery from spinal surgery on April 1, 2020. As a patient-philosopher-artist, I considered my recovery in these sketches with an aim of being present in moments of recovery and capturing, day by day, my own postoperative experiences. Another aim was eventually to share my experiences with other patients trying to meet the demands of recovery and feeling fragile, vulnerable, and uncertain. Recovery is not an event but a process and, indeed, a pursuit.

Figure 1. Untitled 1, from the series Recovery

Media

Oil on canvas, 8" x 11".

This first oil sketch of the series was done at home 2 weeks after my spinal surgery. At this stage of my recovery, I was unable to move or sit; the position of the “subject” in the painting aims to capture the feeling of convalescing rather than the actual positioning of my body. (It would be weeks before I would be able to sit in this position.) Addressing recovery through painting was—for me—a way to cope with the new reality of convalescing and with recovery as an entirely new experience. My goal was to do this painting and others in one sitting—to be “in the moment,” as it were. Addressing the feeling of vulnerability and uncertainty through art was a way to make sense of what my body was going through—and it became a way to regain control over my story and experiences. It was also a way to transform my postoperative bodily experiences into something aesthetically appealing rather than repulsive.

Figure 2. Scar, from the series Recovery

Media

Oil on canvas, 8" x 11".

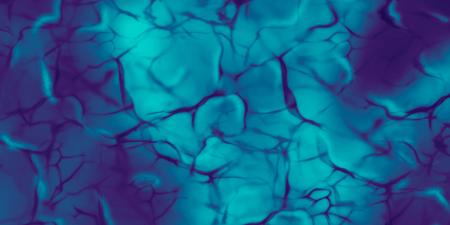

After completing the first painting, it became clear to me that addressing recovery through art could be both therapeutic and emotionally taxing. By capturing my recovery visually, I felt like I was responding to my feelings of hopelessness and pain. For this second work in the series, I chose to work on an “observed abstraction” representing the scar on my back some 2 weeks after surgery. The pallet is true to reality (with colorful bruising, for instance), but the image itself is not a literal color depiction of my skin. Abstract painting presented its own challenges in composition and brush strokes but allowed me to step away from a literal depiction of my body and to be open to a new aesthetic way of engaging with my recovery.

Figure 3. I.V., from the series Recovery

Media

Oil on canvas, 8" x 11".

The third painting of the series was done during week 3 of my recovery. Painted from memory, it is based on my experience of trying to sit up for the first time at the hospital, being careful not to remove the intravenous (IV) line from my arm. The turquoise color of the hospital gown became emblematic for me—almost a symbol of pain and disorientation. Sitting at the edge of my bed from time to time was all I was allowed to do during the first postoperative 48 hours, and my gaze would follow, over and over, the outlines of my arm. This painting is a window onto my world that had shrunk to small, close objects, such as my arm, the IV, or my gown.

Figure 4. Walker, from the series Recovery

Media

Oil on canvas, 8" x 11".

Much like the prior painting, this one was done from memory while I continued to recover at home. It captures another of my common “gazing spots”—my feet. During this time, sitting was allowed but walking wasn’t, and I would stare at my feet and think about walking as a future goal.

Figure 5. Untitled 2, from the series Recovery

Media

Oil on canvas, 8" x 11".

The final image of the series depicts my internal emotional exhaustion during the first days after surgery. A focal point is my hospital-issued red socks. For safety, patients in red socks were not allowed to move unassisted since they could not rely on their legs during the first 48 postoperative hours. Patients in yellow socks were allowed to walk unassisted. However well-intended, red socks remind me of immobility, of the compromised basic capacity to navigate space freely, of the psychological challenge of recovery.

My surgery was ultimately successful, and, in July 2020, I sailed on my 25-foot boat across Lake Ontario to Toronto and back, a goal that had motivated me during 3 months of physical therapy. For 2 weeks after surgery, however, any goal involving movement was aspirational; it was not a given that I would be able to walk well, that nerves in my leg would regenerate well, or that I would resume my normal life. Focusing on painting was a way to create meaning and to make sense of recovery. In retrospect, I can say that turning pain into art was the way to go—I cannot imagine this recovery without these creations.