Abstract

Imagine an exhibition—on a topic like child sexual abuse, dementia, or epilepsy, for example—not typically considered by museums or galleries. The question, then, is Where might such an exhibit be displayed? How about a medical school, for instance? An exhibition of this kind might include visceral psychological portraits and explanatory text tailored to the learning activities of medical students. This article examines these curatorial and ethical considerations.

Exhibitions on Sensitive Topics?

It was shop talk. Four people were sitting around a table at Leiden University in the Netherlands speaking earnestly about the psychological sequelae of child abuse—symptoms and their duration, the impact on brain structures, the deficiencies of treatment. The conversation then turned to the second author’s new art book, Shame and the Eternal Abyss.1 It features images of spinning outpourings of anguish that embody the perplexing sequelae of child sexual abuse.

“It’s curious,” one of our Dutch colleagues remarked; “I just had a conversation with a good friend who is a curator at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. We came to the conclusion that the time might be right to create an exhibition about child abuse, one that incorporates visual artworks no less than research symposiums.” Many delightful conversations ensued, although the exhibition has yet to materialize.

What would it take to bring to fruition an exhibition on a sensitive topic like this? The question is neither rhetorical nor specific to child abuse. Any medically relevant subject matter that’s taboo for any reason, or that’s overlaid with halting inhibitions, might suffice as a representative example: epilepsy, facial disfigurement, and dementia, to name a few. Although each topic has been profoundly represented through artworks, these categories nonetheless don’t easily lend themselves to museums’ and galleries’ priorities, such as marketability. That caveat notwithstanding, how might an exhibition of this nature be made more feasible? And where might it best be displayed? Narrowing the focus of an exhibition to child sexual abuse, for instance, would make its implementation more practical because it would allow the subject matter to be rendered more minutely, thereby facilitating greater viewer comprehension and increasing the subject matter’s relevance to social advocacy.

Exhibiting Child Abuse

There are 4 categories of child abuse: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. Each is further partitioned by intuited or factual differences. For example, child sexual abuse is subdivided into prepubertal and postpubertal classifications.2,3,4

If, indeed, a more circumscribed exhibition on child abuse could be designed—again using the example of child sexual abuse—the more fundamental question is why would anyone want to feature an exhibit devoted to this issue? Sexual abuse is a crime that is an unfathomable harm to a child, and, although this point is clearly of justifiable concern given the potential for adverse viewer reactions, what poses a greater danger, we believe, is censorship. Child sexual abuse is unquestionably a pediatric and public health crisis of epidemic proportions.5,6,7,8,9 Finding an optimal place to display an exhibition of this scope that is informed by trauma more broadly is arguably also a public health priority. Such an exhibition would surely be a conspicuous health initiative if these artworks and their accompanying narration effectively increased emotional engagement with victims of this dreadful ordeal.

Sensitive Exhibitions in Medical Schools

What about medical schools? There is certainly precedent for bringing a topical exhibition to a professional audience; the photographer Richard Ross’s assemblage of photographs, Juvenile-in-Justice, is a case in point. His depictions of incarcerated adolescents were exhibited in 2014 in the hallways of Harvard Law School.10 Immersive by default, the photographs were manifest declamations of injustice, especially befitting for law professors and their students. It should also be noted that displaying artworks in the corridors of medical schools is hardly original. The Harvey Cushing/Whitney Medical Library at Yale School of Medicine routinely hosts exhibitions, such as The AIDS Suite, HIV-Positive Women in Prison and Other Works by Artist/Activist Sue Coe in 2016-2017.11,12

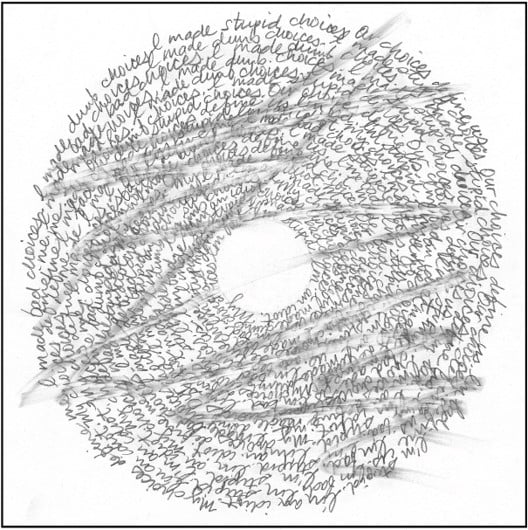

That said, it still might be useful to consider yet another departure from traditional curatorial norms, like a mixed-media exhibition on child sexual abuse—artworks, documentation, symposiums, and performances linked to learning activities created, choreographed, and performed by medical students. Students could wear surgical masks to class, for instance, emblazoned with the letters CSA (for child sexual abuse). Such an activity could serve as both a collective witnessing of CSA survivors who have been shamed into anonymity and a tribute to CSA victims pressured into silence. The corresponding dynamics of shame and silence are also represented in Figure 1, in the form of self-punitive introspections and their erasures.

Figure 1. I’m Bad, by Tania Love Abramson, 2017

Courtesy of the artist.

Media

Pencil, erased, on paper, 14" x 11".

Although this exhibition need not be limited to corridors, it is nonetheless important to keep in mind that these architectural spaces derive their psychological meaning from their ambiance as much as their structure—most notably, their potential for advancing communication and association among those who traverse them,13 like the proverbial gathering around the water cooler. The main instrument for engagement with an exhibition on child sexual abuse would be the alliance between the institutional setting and the fervent artworks themselves.

Immersive by default, the photographs were manifest declamations of injustice.

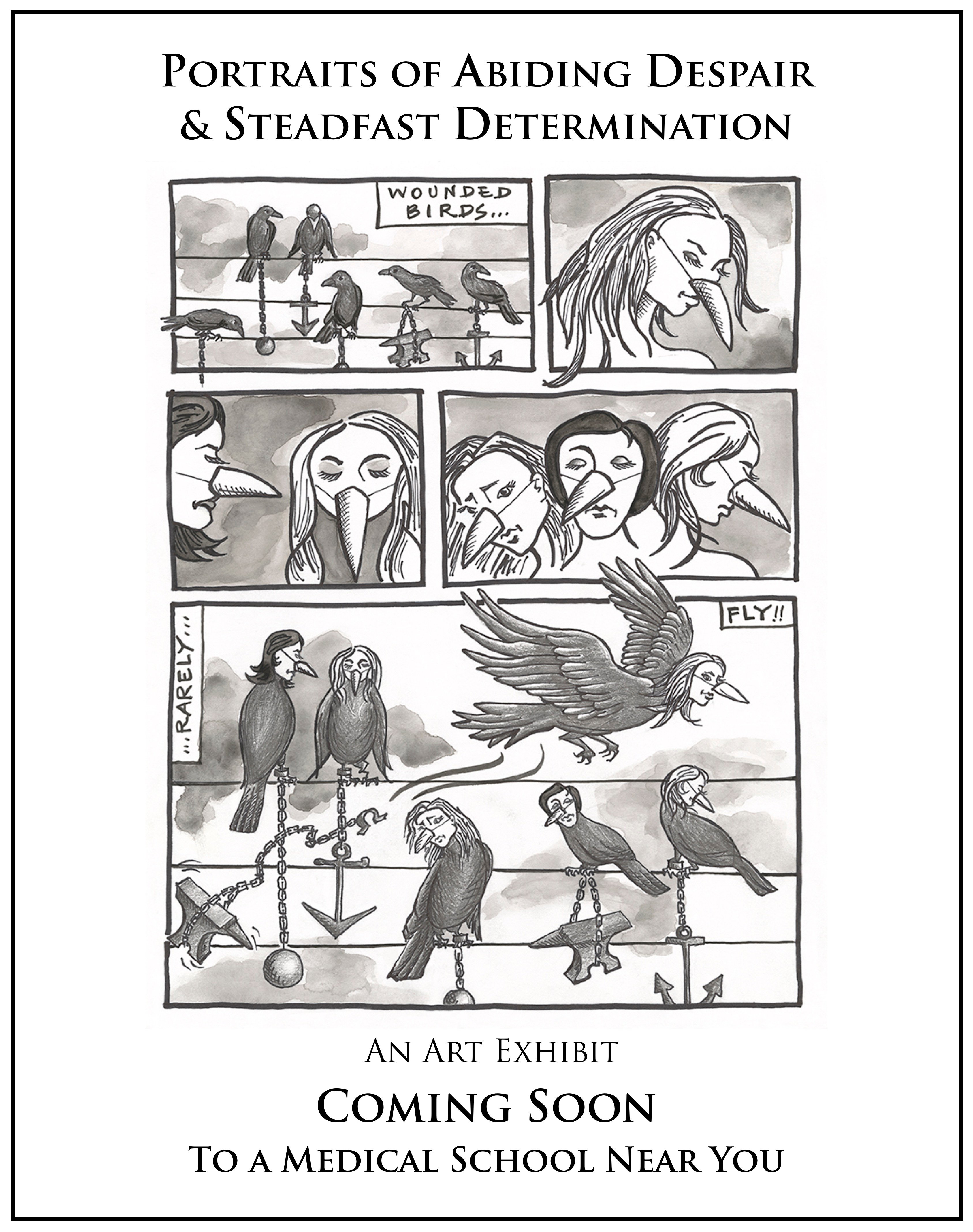

Why hasn’t something of this scope been realized previously in a medical school? Why hasn’t there been an exhibition of artworks—allegorical in character, for instance—of children in the aftermath of sexual abuse—visceral portraits of unrelenting torment no less than resolute courage? We envision something on the order of an exhibition titled Portraits of Abiding Despair and Steadfast Determination. Assuredly, there’s been no lack of attention from the media, which has vividly portrayed child sexual abuse scandals for decades. Perhaps the gatekeepers in the world of art have deemed child sexual abuse too offensive to the sensitivities of viewers—a synergistic repression of the unacceptable, as it were. That supposition, if true, is especially hard to reconcile with the curatorial practices of Holocaust memorials—for example, the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site14 (see Figure 2). Challenging the amnesia around a vast, horrendous crime is the first priority in documenting, and thereby fully comprehending, the Nazi Final Solution.15 Piercing the veil of comforting illusions would serve the same function for child sexual abuse while also reinforcing Mohandas Gandhi’s adage that “truth never damages a cause that is just.”16

Figure 2. Crematorium Ovens, Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site

Photo by Paul R. Abramson, 2016.

Purpose of Child Sexual Abuse Exhibit

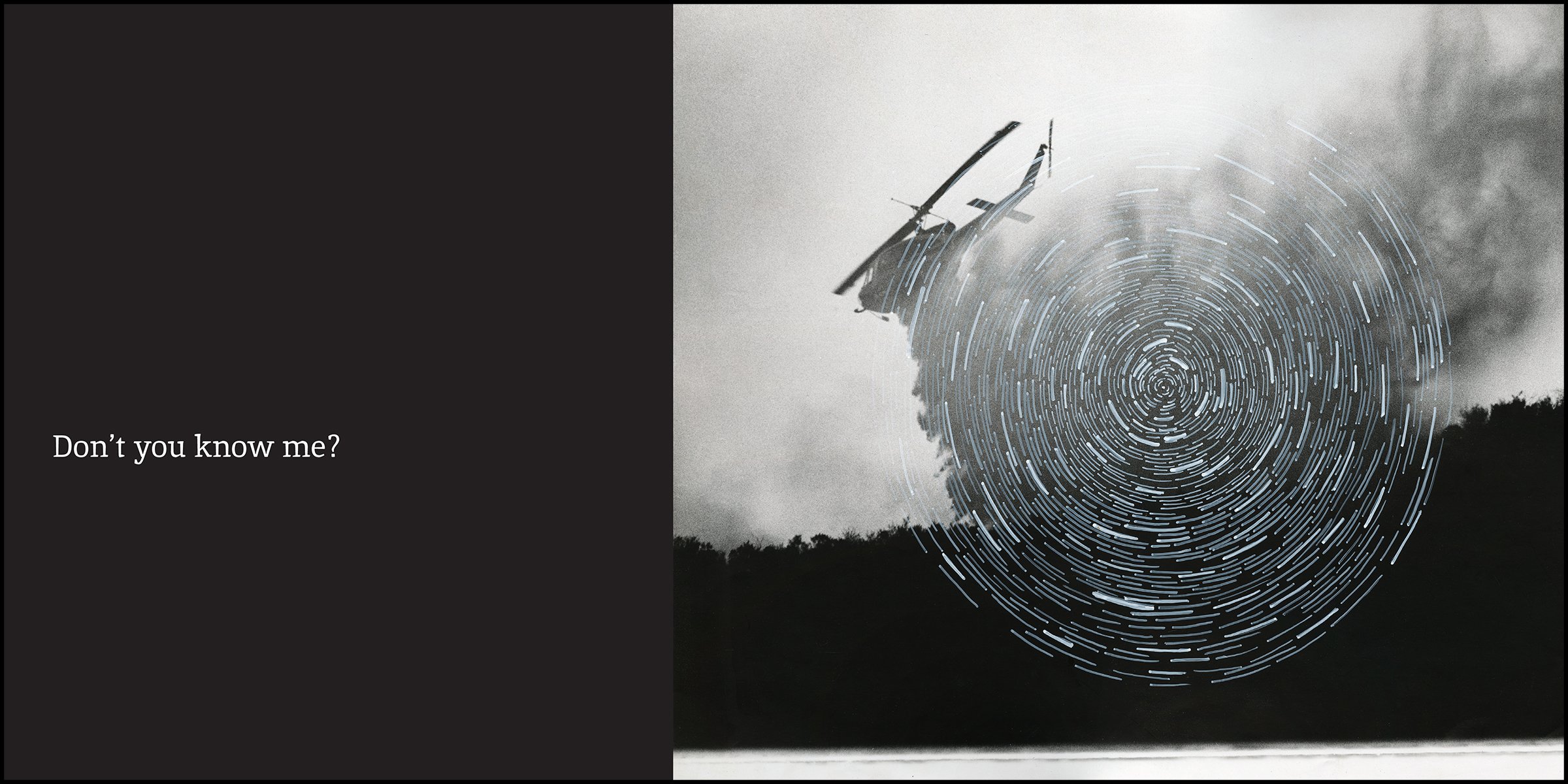

Although the alarming atrocities of child sexual abuse are bad enough, their concealment by the art world is even worse. It’s imperative to stage exhibitions of this nature because their existence alone affirms the putative value of art in connecting dots, including its intrinsic power to rankle. Failing to exhibit artwork of child sexual abuse would also unduly constrict not only survivor narratives but also the language of art more generally—manifest in metaphor, allegory, storyline, and history—or of any linguistic form that can enlighten without constraint and educate without evasion, no matter how indirectly its subject matter is represented or chronicled.17,18,19, 20 One example of indirect representation is an image of a crashing helicopter decimated by a spiraling abyss that is meant to symbolize the emotional tailspin experienced by victims of child sexual abuse (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Lapse of Consciousness, by Tania Love Abramson, 2017

Courtesy of the artist.

Media

Paint pen on found photograph, 16" x 20".

In the best-case scenario, one would want to create an exhibition capable of inducing a transcendent experience,21,22 whereby viewers recognize all of the ramifications of child sexual abuse. For this reason, we have suggested the need for active participation of viewers, symposia, performances, and catalogues in addition to static artworks. It’s even possible to create a playlist of songs that reference child sexual abuse, such as the Girl Child Network Worldwide’s Avantwana-Children Being Abused (Tribute to Betty Makoni)23 and Crying 4 Kafka’s Fuck Mom/Fuck Dad.24

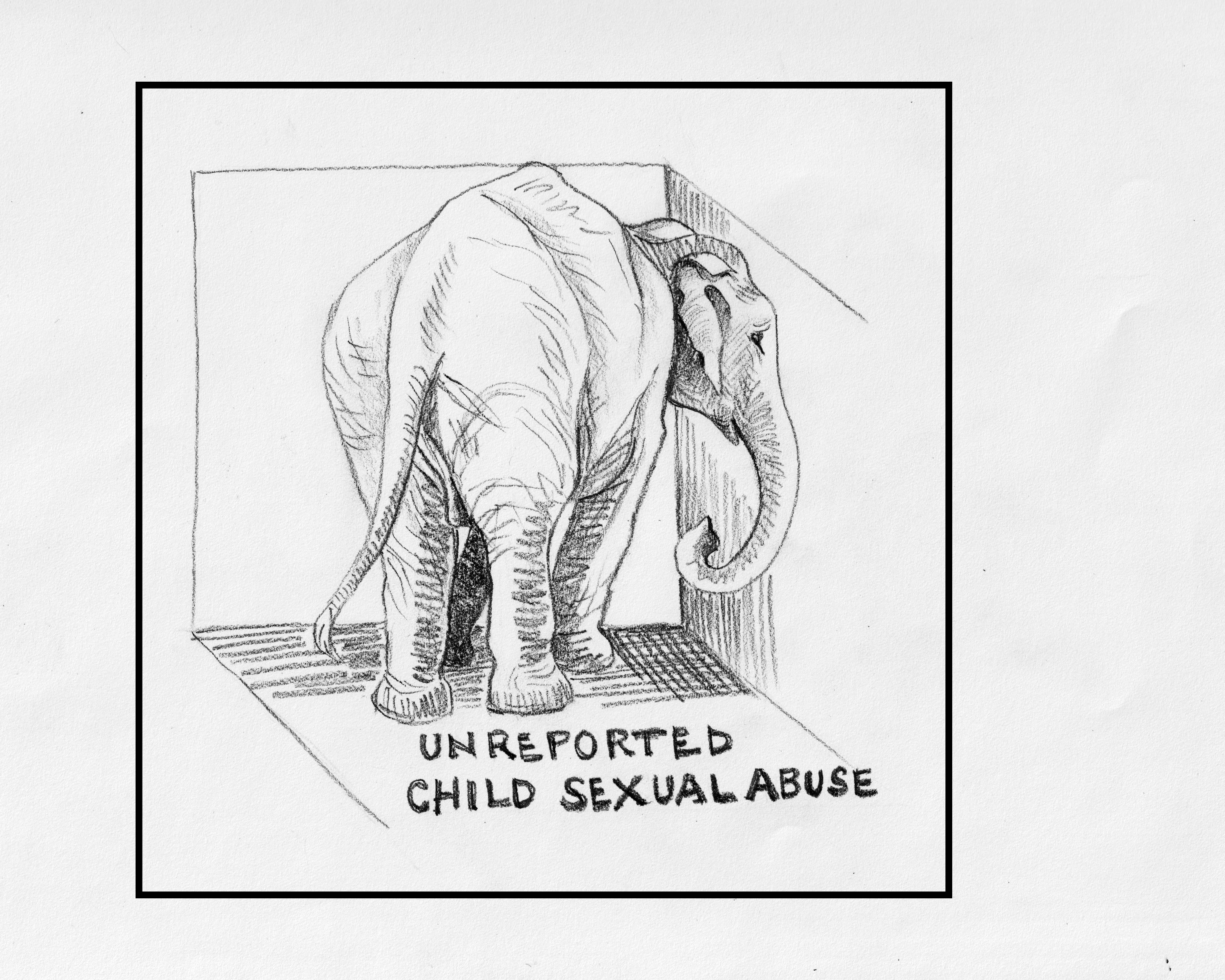

Only through identification can someone begin to understand and empathize with the fact that the sexual abuse of a child is an inconceivable trespass, an emotional annihilation in many respects.25,26 If adult women struggle to report a sexual assault to law enforcement and name their perpetrator, as the #MeToo movement has made abundantly clear, imagine how a child must agonize going through the same criminal process. What credibility does a child have when an adult perpetrator denies the charge? How does a child navigate the legal hurdles? The obstacles to disclosure and resolution are nearly insurmountable for a child (see Figure 4), which is why the crime of child sexual abuse so often goes unreported27 and the psychological fallout, in combination with the long-term health consequences,28 becomes so entrenched.

Figure 4. It’s Always the Elephant in the Room, by Tania Love Abramson, 2019

Courtesy of the artist.

Media

Pencil on paper, 10" x 10".

Although we have emphasized the need for this exhibition to be candid, we also believe that the curated artworks and the choreographed performances should be allusive enough to depict countervailing emotions—outrage and shame, vulnerability and courage or tenacity—as well as empathy and concern, all without ever being willfully antagonistic to viewers. While survivors’ nightmares of abiding despair and their steadfast determination are obviously part of this picture (see Figure 5), so, too, are the stubbornly docile or actively conciliatory bystanders who unconscionably acquiesce to the reassurances of perpetrators of sexual abuse.

Figure 5. Exhibition Poster Mockup, by Tania Love Abramson, 2019

Courtesy of the artist.

Media

Ink on paper, 8.5" x 11".

If indeed an exhibition of this nature ever makes it past the customary barriers to whisper through the corridors of medical schools, the hope, ultimately, is that it propels physicians and their students to act upon what they have experienced. Child sexual abuse is an emotionally debilitating crime. Overcoming the reluctance to report suspected cases of child sexual abuse, particularly when the evidence is subtle, would be an especially significant outcome. Active involvement in organizations dedicated to the prevention of child sexual abuse, such as Darkness to Light,26 would be an equally meaningful consequence.

References

-

Abramson TL. Shame and the Eternal Abyss. Joshua Tree, CA: Asylum 4 Renegades Press; 2017.

-

Abramson PR. Sarah: A Sexual Biography. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1984.

-

Abramson PR. Screwing Around With Sex: Essays, Indictments, Anecdotes, and Asides. Joshua Tree, CA: Asylum 4 Renegades Press; 2017.

-

World Health Organization. Responding to children and adolescents who have been sexually abused: WHO clinical guidelines. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259270/9789241550147-eng.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed March 5, 2020.

-

Jenny C, Crawford-Jakubiak JE; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of children in the primary care setting when sexual abuse is suspected. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e558-e567.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of sexual violence against children and use of social services—seven countries. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6421.pdf. Published June 5, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2019.

-

Kellogg N; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):506-512.

- Helton JJ, Carbone JT, Vaughn MG. Emergency department admissions for child sexual abuse in the United States from 2010-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(1):89-91.

-

World Health Organization. Responding to children and adolescents who have been sexually abused. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/violence/clinical-response-csa/en/. Published October 19, 2017. Accessed November 15, 2019.

-

Ross R. Juvenile in Justice: a photo exhibit by Richard Ross. Harvard Law Today. March 24, 2014. https:/today.law.harvard.edu/juvenile-justice-photo-exhibit-richard-ross/. Accessed February 06, 2020.

-

Yale Medical Historical Library. Past exhibitions. https://library.medicine.yale.edu/historical/explore/exhibits. Accessed February 06, 2020.

-

Cummins M. “AIDS Suite” exhibit at medical library showcases work of artist/activist Sue Coe. Yale News. September 8, 2016. https://news.yale.edu/2016/09/08/aids-suite-exhibit-medical-library-showcases-work-artistactivist-sue-coe. Accessed February 06, 2020.

-

Luckhurst R. Corridors: Passages to Modernity. London, UK: Reaktion Books; 2019.

-

Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site website. https://www.kz-gedenkstaette-dachau.de/index-e.html. Accessed March 5, 2020.

-

Abramson TL, Abramson PR. Charting new territory: the aesthetic value of artistic visions that emanate in the aftermath of severe trauma. Contemp Aesthet. 2019;17:1-2.

-

Gandi M. Gandhi on Non-violence: Selected Texts From Mohandis K. Ghandi’s Non-violence in Peace and War. Merton T, ed. New York, NY: New Directions; 1965.

- Abramson TL, Abramson PR. Arkoun Vannak: a tribute to a heroic Cambodian artist. Vis Inquiry. 2019;8(1):79-83.

- Abramson PR, Abramson TL. Visual and narrative comprehension of trauma. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(6):e535-e543.

-

Goodman N. Languages of Art. Cambridge, MA: Hackett; 1976.

-

Herder JG. Selected Readings on Aesthetics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2006.

-

Phillips G, Kaiser P, eds. Harold Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute; 2018.

-

Spaid S. The Philosophy of Curating: From Works to World. New York, NY: Bloomsbury; 2020.

-

Girl Child Network Worldwide. Avantwana–Children Being Abused (Tribute to Betty Makoni). https://music.apple.com/au/album/avantwana-children-being-abused-tribute-to-betty-makoni/472431195?i=472431237. Accessed February 06, 2020.

-

Crying 4 Kafka. Fuck Mom/Fuck Dad. https://soundcloud.com/crying-4-kafka/fuck-mom-fuck-dad. Accessed February 06, 2020.

- Abramson TL. Unchain my anguish: a feminist take on art and trauma. Fem Rev. 2019;122(1):189-197.

-

Darkness to Light website. https://www.d2l.org/. Accessed March 3, 2020.

-

Sharples T. Study: most child abuse goes unreported. Time. December 2, 2008. http://content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1863650,00.html. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Irish L, Kobayashi I, Delahanty DL. Long-term physical health consequences of childhood sexual abuse. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(5):450-461.