Abstract

The concept of mortal time is useful in exploring what the hospice care framework might offer nonhospice clinicians. While hospice patients seem distinct from those in other settings, life-threatening serious illness brings with it profound vulnerability that permeates the atmosphere of caregiving. Hospice clinicians lean into this vulnerability, seeking to make meaning for patients and families in the critical present. Clinicians elsewhere can strive to overcome it, working to save themselves and their patients for a rosier future. Mortal time signals the shared human condition, however, and, as such, it can be an entry point for solidarity among patients and coworkers, strengthening both.

Vulnerability and Mortal Time

What can the hospice approach to patient care offer clinicians in acute care and the clinic? The question itself implies that a clear marker divides patients in hospice care from seriously ill patients “outside” hospice care. But are the 2 types of patients so different? Using the concept of mortal time,1 I argue that the vulnerability of seriously ill patients—that is, their exquisite susceptibility to harm—impels clinicians who treat such patients both inside and outside of hospice to provide care that best serves those patients as they acknowledge the existential threat posed by that vulnerability. Unlike rescue care, however, hospice care is organized around the reality of human finitude (ie, mortal time) that vulnerability brings to light, plumbing it as a resource for hope in the human condition rather than as a problem to solve. Reframing vulnerability as mortal time provides an avenue for seeking common ground across diverse clinical approaches.

McQuellon and Cowan describe mortal time as occurring when the patient and family grapple with the prospect of unavoidable personal death.1 Learning the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness often marks the beginning of mortal time. It might span days, months, or years. The diagnosis holds and colors the life experience of calamity, regardless of what is being done about it or the patient’s condition in the moment.

When some of these patients with a terminal illness wish to benefit from the comprehensive support of the Medicare Hospice Benefit (MHB), the US health care system asks them to make a difficult choice. Unlike palliative care, which can accompany curative measures, hospice reimbursement mechanisms prohibit them.2 In choosing hospice care, therefore, caregivers and patients enter an accentuated phase of mortal time. They must adopt a way of life robbed of the illusion of infinitude and embrace a “critical present” of sorts.3 Supporting that specific vulnerability, as hospice does, becomes a skill relevant to acute care settings in view of the difficulty in differentiating between the seriously ill and the dying, both living in mortal time.

Making Meaning in Mortal Time

On an intake visit, my prospective hospice home care patient towered over me as he answered the door, sporting his T-shirt, Bermuda shorts, and tracheostomy. Jack (not his real name) had head and neck cancer. He ushered me through the house to the back porch, as it was an unusually warm early spring morning. He sprayed the patio table with glass cleaner and wiped it down before we sat down to discuss his home care plan.

Was Jack dying? Certainly, but not immediately. He sought companionship from hospice to navigate the path ahead. His future was limited and unknowable, even as he coped with the routines of his daily life, including tube feedings. Yet he had the wherewithal to recognize and make the most of the good weather as we discussed his situation.

Many who are unfamiliar with the framework of hospice care believe that finding “peace” in dying is the best hope possible and that such is hospice’s goal. But this assumption reveals a failure of imagination. Hospice’s far broader agenda is to enable patients and families to extract the most meaning they can from living each hour and minute—to expand their universe as the now unstoppable illness tries to contract it. Opportunity exists in dying that no other phase of living offers, precisely because mortality is so real. Patients like Jack are willing to seize the opportunity to live each day in defiance of death, not waiting for the illness’ progression to rob them of it, along with so much else.

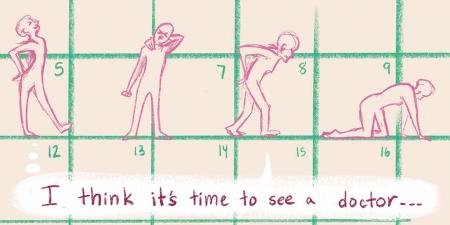

How was Jack different from the seriously ill patients that acute care clinicians care for? Unlike many seriously ill patients in acute care settings, he was conscious, alert, able to perform activities of daily living, not yet bedbound, and able to make the most of the present moment as he grappled with the unknown. Yet his disease made him fragile. Benefitting from advances in chemotherapy and immunotherapy, many cancer patients live in a similar kind of limbo, yoked to a terminal diagnosis, yet far from actively dying. They navigate their awareness of mortal time along with the demands of “normal” life, balancing medical visits and a fluctuating sense of their own wellness.

As technology becomes ever more elaborate, sorting the rescuable patients from the unrescuable—the “living” from the “dying”—gets trickier.

Not-yet-hospice-ready patients with serious illness can focus on the future. They and their families hope their current unfortunate or even dire circumstances are temporary, that the horizon of finality will recede. Propitious treatments continue on an outpatient or inpatient basis. Setbacks requiring acute or critical care might even reinforce that tomorrow-oriented perspective. If illness progresses, however, clinicians recognize that their sickest patients face a constrained time horizon, even when no one has officially categorized them as “Dying.” And as technology becomes ever more elaborate, sorting the rescuable patients from the unrescuable—the “living” from the “dying”—gets trickier. The length of time patients spend under hospice care illustrates the reluctance to give up on rescue. Although the MHB is intended for people with a life expectancy of 6 months or less,2 in 2018, 50% of hospice patients spent 18 days or more in hospice.4

Mortal Time Without Meaning

After the 1990 passage of the Patient Self-Determination Act,5 advocates for excellence in end-of-life care recommended advance care planning (ACP) as the major mechanism for negotiating a transition from rescue care and its potential for bad dying to management of life-threatening illness. Yet, in too many cases, conversations and documents fail to forestall unwanted or inappropriate care.6,7 One reason is that ACP assumes (erroneously) that hospitals can enact the patient’s goals in a meaningful way. In truth, the atmosphere of urgency in critical care settings often forecloses this possibility, especially when patients are very sick. Treatment plans generally follow one of only 2 tracks: (1) full code and “do everything to rescue from death” or (2) “do not resuscitate,” in which case the treatment plan might be less clear. This bifurcation of end-of-life care is pragmatic rather than patient centered. It enables time-pressured clinicians to manage multiple patients more easily, since most are considered rescuable. Accordingly, clinicians need not question the clinical momentum8 that “moves things along”9 for most patients. The path is clear. By the time a tipping point is finally reached to call the patient Dying,10 the person is too sick to interact. The best opportunities that hospice offers for finding meaning in mortal time have often been lost.

Many seriously ill patients share hospice patients’ profound vulnerability, even if they continue down a rescue path. They live in mortal time, yet without the refuge that an acknowledgement of this fact might provide. Their clinicians, busy with rescue’s demands, deepen patients’ fragility as they weaponize technology to both hold death back and shield themselves from grappling with it. It is bruising work for them.

But the intensity of the critical care environment demands unwavering focus. Caregivers cannot afford to slow down enough to take in the frailty that patients present. It feels dangerous. It is wearing enough to care for them, much less to enter their liminality. Thankfully, managing the “stuff” connected to seriously ill patients, along with their sheer numbers, means that confronting human inadequacy and helplessness—a part of the territory of serious illness and dying—can be mostly ignored, along with the bruises.

How Stillness Creates Space for Meaning

But human inadequacy and helplessness cannot be ignored forever. Moral distress is rampant, causing clinicians to leave their professions,11 as repeated exposure to morally distressing events is both inevitable12 and unrelieved by improving their rescue skills.13 If patients teach “the reality of the vulnerability of living,”14 the self-grounding needed to tap into this truth can be elusive. Rushton has suggested that clinicians seize moments for stillness in their work to buffer its harms and allow new truths to emerge.15 Pausing allows time for breath, slows the pace of interaction, invites new questions, and supports a shift to stillness rather than reactivity. Now it becomes possible to notice the gravity of this moment and its inherent ambiguity. Only by seeking stillness can we open a space for leaning into our shared humanity and helplessness rather than shunning it. Hess offers the patient’s narrative as a way to support the rugged pathway walked by patients and clinicians.16 Information the family shares about the patient’s interests furnishes something to talk about while delivering care, regardless of the patient’s ability to respond.

We have established that patients with serious life-threatening illness live in mortal time and that some might be undefended by the illusion of an unlimited future. Those journeying alongside them, loved ones and clinicians, can find each other in mortal time.1 This state of being diverges from polite society, which does not support such awareness.17 The rescue environment of acute care likewise fails to sanction it. Acknowledging the reality of finitude can be a deviant, subversive, and therefore powerful act. Loosening one’s grasp on a retreating future is not to despair but to avail oneself of new benefits. It shifts one’s weight, literally and figuratively, to seek stillness and be open to the deep realities of human presence and human helplessness. The framework of hospice care incorporates these uncertainties and puts them to use, recognizing how unique mortal time can be in human experience. Along with creating endemic anxieties and struggles, mortal time brings family members together to honor a life precious to them. It allows sharing of memories, asking forgiveness, healing of relationships, and converting final moments into legacies of meaning.

Mortal Time as Common Ground

Acute care clinicians labor differently than hospice and palliative care clinicians. But their patients’ fragility is similar. An unimaginative health care system imposes falsely dueling categories of care, rescuable and unrescuable, and this division will likely persist. Can hospice and palliative care clinicians’ familiarity with mortal time offer common ground to their fellow clinicians engaged in rescue, an opportunity for drawing strength from each other? To gain the courage and balance to sojourn there, it is advisable to link arms, to seek solidarity across the divide that mortal time imposes.18

Bruce Jennings suggests that it is both a moral duty and a social necessity to demonstrate solidarity with the dying by standing up beside, for, and with those living through mortal time. He advocates “civic palliative care,” arguing that families and patients should not have to navigate mortal time on their own. He makes the moral case that “[t]he object of civic palliative care is the patient’s embodied and relationally embedded personhood, not just her disease, symptoms, or isolated body and self.”19 It is this personhood that serious illness buries and that hospice seeks to resurrect.

Every clinician seeks to provide care that best serves the patient. How can we leverage this solidarity of purpose to learn from each other during the patient’s journey through mortal time? I suggest 3 ways that clinicians who are troubled by their patients’ mortal time (and their own) can explore common ground: (1) by perusing how the hospice frame of care emphasizes the strengths and opportunities in this unique time of life; (2) by noticing how urgency distracts and keeps “us” (humans still upright and living in the illusion of our self-reliance) from tapping into the vulnerability of mutual interdependence and ambiguity about the future that we share with humans abed (our patients); and (3) by finding ways to forge and maintain relationships with our colleagues—across disciplines, professions, and care settings—to hold each other up in this important work.

Some months passed between that spring morning and the last days of Jack’s life in a hospice facility. It was a tough road. He and his family were fearful, but their eyes were open; they had control of each step along the way; and they were not alone. Mortal time and its attendant vulnerability can bear us up if we have the courage to reach for friends and fellow caregivers who are willing to go there with us—all of us living and dying, together.

References

-

McQuellon RP, Cowan MA. The Art of Conversation Through Serious Illness: Lessons for Caregivers. Oxford University Press; 2010.

-

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare hospice benefits. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed August 23, 2022. https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/02154-medicare-hospice-benefits.pdf

-

Chapple HS. Rescue: faith in the unlimited future. Sociology. 2015;52:424-429.

-

NHPCO releases new facts and figures report on hospice care in America. News release. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; August 17, 2020. Accessed August 23, 2022. https://www.nhpco.org/hospice-facts-figures/

-

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, HR 5835, 101st Cong (1989-1990). Accessed August 23, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/5835

-

Morrison RS, Meier DE, Arnold RM. What’s wrong with advance care planning? JAMA. 2021;326(16):1575-1576.

-

Shapiro SP. Speaking for the Dying: Life-and-Death Decisions in Intensive Care. University of Chicago Press; 2019.

- Kruser JM, Cox CE, Schwarze ML. Clinical momentum in the intensive care unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(3):426-431.

-

Kaufman S. And a Time to Die: How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life. Scribner; 2005.

-

Chapple HS. No Place for Dying: Hospitals and the Ideology of Rescue. Routledge; 2016.

- Whittaker BA, Gillum DR, Kelly JM. Burnout, moral distress, and job turnover in critical care nurses. Intern J Stud Nurs. 2018;3(3):108-121.

- Epstein EG, Hamric AB. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J Clin Ethics. 2009;20(4):330-342.

-

Chapple HS, Gillen M. Help wanted: technology, ICU nurses, and death. In: Deem M, Lingler J, eds. Nursing Ethics: Normative Foundations, Advanced Concepts, and Emerging Issues. Oxford University Press. Forthcoming.

-

Churchill LR, Fanning JB, Schenck D. What Patients Teach: The Everyday Ethics of Health Care. Oxford University Press; 2013.

- Rushton CH. Ethical discernment and action: the art of pause. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2009;20(1):108-111.

- Hess JD. Gadow’s relational narrative: an elaboration. Nurs Philos. 2003;4(2):137-148.

-

Solomon S, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T. The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life. Random House; 2015.

-

McGhee H. The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together. Profile Books; 2021.

-

Jennings B. Solidarity, mortality: the tolling bell of civic palliative care. In: Staudt C, Ellens JH, eds. Our Changing Journey to the End: Reshaping Death, Dying, and Grief in America; vol 2. Praeger; 2013:271-288.