Abstract

This article outlines the history of international humanitarian law vis-à-vis conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) from the promulgation of the Lieber Code in 1863 until the adoption in 2019 of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2467. This article considers how a survivor-centered approach to CRSV has emerged, particularly since 2008. The authors identify 3 significant clinical, ethical, and legal lessons: (1) international humanitarian law, as articulated in the Geneva Conventions and other legal instruments, requires clinicians to adopt a holistic approach to care; (2) during or after any conflict in which CRSV has allegedly been inflicted, a clinician may be required to provide evidence to an official investigatory body or court; and (3) infliction of rape in any conflict may equate to commission of torture and possibly genocide, a reality which obliges every clinician to appreciate that a patient may simultaneously be a victim of human rights violations and of crimes.

Conflict-Related Sexual Violence Law Before 1948

It was a sign of the far-sightedness of President Abraham Lincoln, a lawyer by profession, that on April 24, 1863, he issued what is commonly known as the Lieber Code.1 This groundbreaking legal manual and by-product of the US Civil War is indelibly associated with the Berlin-born Francis Lieber, a naturalized US citizen and academic.2,3 For all of its defects and deficiencies when viewed from the standpoint of the 21st century, Articles 44 and 47 of the Lieber Code were ahead of their time in that each was drafted in a way that embodied an express reference to rape. Under Article 44, “All wanton violence committed against persons in the invaded country” and inter alia “all rape” are “prohibited under the penalty of death, or such other severe punishment as may seem adequate for the gravity of the offense.”1 Under Article 47 of the Lieber Code, “Crimes punishable by all penal codes, such as arson, murder, maiming, assaults, highway robbery, theft, burglary, fraud, forgery, and rape, if committed by an American soldier in a hostile country against its inhabitants, are not only punishable as at home, but in all cases in which death is not inflicted, the severer punishment shall be preferred.”1

Not surprisingly, the Lieber Code forms an integral part of the background of modern legal manuals devoted to the conflict-focused area of international law now known as international humanitarian law (IHL), otherwise known as the law of war or law of armed conflict. Such manuals include the US Department of Defense Law of War Manual. Its preface, signed by Stephen W. Preston, general counsel of the Department of Defense, openly acknowledges the debt owed to the Lieber Code:

This manual has many distinguished antecedents that have provided important guidance to the US Armed Forces. For example, General Order No. 100, the Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field, commonly known as the Lieber Code, was prepared by Professor Francis Lieber and approved by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War in 1863.4

Notwithstanding the express references to rape in Articles 44 and 47 of the Lieber Code and the implicit prohibitions against rape in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907,5,6 IHL and its counterpart, international criminal law (ICL),7,8 were slow to acquire effective mechanisms for punishing international crimes. This was demonstrated by the mass inhumanities, including rapes, unquestionably committed during the First World War9,10 and by the widespread impunity that followed.11

Even after the Second World War, IHL and ICL were likewise slow to recognize rape as a weapon of war that needed to be treated as a priority to be confronted. Thus, despite compelling rape-related evidence incriminating the armed forces of Germany12,13,14 and, indeed, some of her enemies,15 rape was not expressly mentioned in either the agreement relating to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg or the Charter of the Tribunal, as adopted by France, the United Kingdom (UK), the United States, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) on August 8, 1945.16 Nor was rape expressly mentioned in the indictment issued before the start of the historic first postwar trial held in Nuremberg.16 In consequence, it is hardly surprising that there is no express reference to rape in the judgment handed down by the four judges—from France, the UK, the US, and the USSR respectively—at the close of this breakthrough in international criminal justice that unfolded from November 14, 1945 until October 1, 1946.16

By contrast, rape was expressly cited in the indictment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East17 (despite not being expressly mentioned in the charter, dated January 19, 194618). Furthermore, in the context of crimes against humanity, rape was expressly discussed in the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, as handed down in 1948. Nevertheless, the victims of rape were not invited to present evidence before the tribunal in Tokyo and, accordingly, their voices were not heard.19

By 21st century standards, it is astounding that rape was omitted from the indictment prepared by the American, British, French, Soviet prosecutors for the first postwar trial at Nuremberg, although French and Soviet prosecutors went on to adduce evidence of rape before the tribunal there.19 It is equally astounding that, although the postwar tribunal in Tokyo considered the issue of rape to a far greater extent, it overlooked the pressing of thousands of “comfort women” into enforced prostitution in “Japanese military brothels.”19 These omissions, however, may have reflected a transnational culture that was uncomfortable with the crime of rape and, in a sense, treated it as a taboo. The transcript of an address, published on August 24, 1953, by US Supreme Court Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson, who had previously served as the chief US prosecutor in Nuremberg, is illustrative of this culture. In the context of what he depicted as the “large gap between the number of estimated crimes and the number of reported crimes,” Jackson turned his attention to a question of eternal importance which he articulated as follows: “Why do people not report crimes?” In response, he said something characteristically honest that offers a glimpse into one of the brains behind the indictment and related prosecutions at Nuremberg: “Sometime ago I read of a lawyer who advised his daughter not to appear as complaining witness in a rape case. I had a lot of sympathy with him. I am not sure, with the modern methods of publicity, that I would report a rape in my family. We need every possible incentive to disclose, not to cover up, crime.”20

Without in any way wishing to undermine the lasting legacy of a legal heavyweight whose place in history is secure, the authors of this article cannot imagine any judge, let alone any member of the US Supreme Court, venturing such thoughts in public in the 21st century. Yet Jackson evidently had no qualms about venturing them in 1953.

Conflict-Related Sexual Violence Law Since 1948

Since 1948, the year in which the tribunal in Tokyo handed down its judgment, a sea change has occurred in IHL and its approach to rape as well as forms of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). In turn, this sea change has had deep implications, not least of all for members of the legal profession,21,22 the medical profession,23,24,25,26 and other related professions. The sea change began to crystallize upon the adoption, on August 12, 1949, of the Fourth Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (to which the US is a state party).

Under Section 1, Article 27 of the convention, “Women shall be especially protected against any attack on their honour, in particular against rape, enforced prostitution, or any form of indecent assault.”26 Article 27 plugged the conspicuous gap in IHL that existed in view of the shortcomings of the 1945 charter and subsequent judgment of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. To quote from the Commentary to the Fourth Geneva Convention, published in 1958 by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the guardian of the 4 Geneva Conventions:

Paragraph 2 [Article 27.2] denounces certain practices which occurred, for example, during the last World War, when innumerable women of all ages, and even children, were subjected to outrages of the worst kind: rape committed in occupied territories, brutal treatment of every sort, mutilations etc. In areas where troops were stationed, or through which they passed, thousands of women were made to enter brothels against their will or were contaminated with venereal diseases, the incidence of which often increased on an alarming scale.

These facts revolt the conscience of all mankind and recall the worst memories of the great barbarian invasions. They underline the necessity of proclaiming that women must be treated with special consideration. That is the object of this paragraph, which is based on a provision introduced into the Prisoners of War Convention in 1929, and on a proposal submitted to the International Committee [of the Red Cross] by the International Women’s Congress and the International Federation of Abolitionists.27

Although Article 146 of the Fourth Geneva Convention imposed an obligation on every state party “to provide effective penal sanctions” for any “grave breaches” of the same convention,26 none of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 created any international criminal court with prosecutorial and judicial arms. Thus, for decades after 1949, the fine words in these 4 conventions could not be effectively enforced unless a state subject to them either voluntarily chose to abide by their terms or, in the event of a breach by military personnel or civilians under their jurisdiction, voluntarily opted to enforce them via the domestic military or criminal justice systems. Against this unsatisfactory background, rape and other forms of CRSV remained an odious feature of various conflicts, such as the one in which US forces were immersed in Vietnam until the US withdrawal in 197528 and the one in Afghanistan in the years after the Soviet invasion in 1979.29

On May 25, 1993, the post-1946 sea change in IHL was given international teeth, albeit in a limited geographical context, when the UN Security Council (UNSC) established the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).30 When the US endorsed this move, its ambassador to the UN, Madeleine Albright, proclaimed: “We must ensure that the voices of the groups most victimized are heard by the Tribunal. I refer particularly to the detention and systematic rape of women and girls, often followed by cold-blooded murder.”31

On a global basis, more international teeth were added to IHL after the opening of the International Criminal Court (ICC) on July 1, 2002, upon the coming into force of the Rome Statute on the International Criminal Court of 1998 (to which the US is a signatory but not a state party).32 Article 7.1(g) of the Rome Statute defines a crime against humanity in a way that encompasses “Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity” provided any such “form of sexual violence” is “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.” Meanwhile, under Article 8 (2)(a)(xiii) and other provisions of the Rome Statute, “sexual violence” of lesser gravity is capable of being a war crime.33 Since 1993, cases involving alleged CRSV have been brought before the ICTY and ICC in addition to other international criminal courts, notably the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL).

For clinicians, the impact of these developments was illustrated by the pivotal role of Dr Idriz Merdžanić in the ICTY case of Prosecutor v Milomir Stakić.34,35 In the words of a profile published by the ICTY, Dr Merdžanić was “a Bosnian doctor who treated victims of the Trnopolje Camp” and who “testified on 10 and 11 September 2002 in the case against Milomir Stakić.”36 In a judgment handed down on July 31, 2003, the ICTY found Stakić guilty of various crimes, including persecution committed by acts such as rape and sexual assault. To quote from the ICTY profile:

In the months that Dr. Merdžanić was at the [Trnopolje] camp, he treated women who had been raped. From the clinic window, Dr, Merdžanić and his colleagues could see men go into the women’s sleeping quarters at night, flash their lights at the women they liked and take them out. Some of the women later came to the clinic to ask for help. Dr. Merdžanić succeeded in having a number of them sent to the gynaecological ward in Prijedor to investigate their allegations. He later found out that they had indeed been raped.36

In its judgment, the ICTY repeatedly cited the evidence presented by Dr Merdžanić, which it evidently regarded as credible.34,35,36

What can clinicians learn from the case of Stakić? Perhaps the most obvious moral of the case is that, in exceptional conflict-related circumstances, a clinician may face incidents of CRSV as harrowing as those witnessed by Dr Merdžanić. Despite the stresses these incidents will unavoidably create, clinicians must maintain their professionalism, exercise moral courage, and reach rational decisions. In parallel, as explained in more detail below, clinicians must appreciate that any episode of CRSV unfolding before their eyes may one day be the subject of an official investigation or court case in which their actions or omissions are scrutinized.

Accordingly, however difficult it might be under the intensely pressurized conditions and climate of coercion that any conflict is inclined to generate,37 a clinician must comply with the law and the principles of medical ethics, such as those adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1982.38 To these ends, some professional bodies have published guidance aimed at clinicians serving within or beyond the armed forces. An example of the former is “Ethical Decision-Making for Doctors in the Armed Forces: A Tool Kit,” a joint publication of the British Medical Association and its Armed Forces Committee.39 The opening 2 paragraphs and the “key messages” constituting the final paragraphs encapsulate the legal and ethical challenges facing physicians in the regular armed forces of a democratic state subject to the rule of law:

Doctors working in the armed forces owe the same moral obligations to their patients, whether comrades, enemy combatants or civilians, and are subject to the same ethical standards as civilian doctors. The extremity of the circumstances in which military doctors operate can make it difficult at times to understand how best to fulfil these obligations.

Unlike the majority of civilian doctors, military doctors can also be subject to significant competing or dual loyalties. Ethical obligations to individual patients may come into conflict with the demands of military necessity or with perceived obligations to the operational unit. For example, a doctor’s duty of confidentiality will potentially come into tension with his or her obligation to keep commanders informed of an individual patient’s fitness for active service. Of course these simultaneous duties do not inevitably create a conflict, and neither are they unique to military medicine. Occupational health physicians and prison doctors have similar dual obligations, which must be carefully managed…

Key messages

- Abusive situations rarely emerge suddenly.

- Perpetrating, being present at, being aware of, or being suspicious of abuse, and doing nothing about it, are all unacceptable and unjustifiable.

- Physicians should be aware of the factors which can influence the likelihood that they will recognise or report unethical or abusive practices.

- Physicians should keep their own record of all action they take in respect of reporting abuse.39

Clinicians can learn at least one other thing from the successful prosecution of Stakić and his conviction in 2003. The case of Stakić belongs to a wider pattern of prosecutions in which CRSV has been given the prominence it deserves; in turn, that pattern underlines the linkage between CRSV, the essentiality of post-violence health care, and the delivery of criminal justice. In the words of the UN publication on the ICTY, ICTR, and SCSL:

Sexual violence form part of convictions of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Sexual violence against civilians also takes various forms and constitutes or is part of different crimes at the three courts. For example, rape and other forms of sexual violence constitute or form part of the crimes of torture, enslavement, sexual slavery and persecution as crimes against humanity; of torture and outrages upon personal dignity as war crimes; and of serious bodily or mental harm as genocide.40

Centering Survivors

Since 2008, a new phenomenon has emerged—the UN-backed “survivor-centered approach” to CRSV.41 This approach is a by-product of a string of CRSV-focused resolutions of the UNSC.42 The first was Resolution 1820, adopted by the UNSC, with US support, on June 19, 2008. Among its provisions is the following:

[Urging] all parties concerned, including Member States, United Nations entities and financial institutions, to support the development and strengthening of the capacities of national institutions, in particular of judicial and health systems, and of local civil society networks in order to provide sustainable assistance to victims of sexual violence in armed conflict and post-conflict situations.43

More recently, on April 23, 2019, the UNSC adopted Resolution 2467 on CRSV, with eventual US support.44 Tellingly, its preamble not only acknowledges “the responsibilities of States to end impunity and to prosecute those responsible for crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, perpetrated against civilians,”44 but also recognizes “the need for a survivor-centered approach in preventing and responding to sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations,”44 the parallel “need for survivors of sexual violence to receive non-discriminatory access to services such as medical and psychosocial care to the fullest extent practicable,” and the related “need to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”44 The operative paragraphs of Resolution 2467 include one reiterating a previous “demand” of the UNSC “for the complete cessation with immediate effect by all parties to armed conflict of all acts of sexual violence and its call for these parties to make and implement specific time-bound commitments to combat sexual violence.”44 Another calls on “all Member States to ensure that survivors of sexual and gender-based violence in conflict in the respective countries receive the care required by their specific needs and without any discrimination.”44 Resolution 2467 goes on to affirm “that victims of sexual violence, committed by certain parties to armed conflict, including non-state armed groups designated as terrorist groups, should have access to national relief and reparations programmes, as well as health care, psychosocial care, safe shelter, livelihood support and legal aid.”44

All in all, as the UN emphasizes, Resolution 2467 is “a powerful new instrument in our fight to eradicate this heinous crime, significantly strengthening prevention through justice and accountability and affirming, for the first time, that a survivor-centered approach must guide every aspect of the response of affected countries and the international community.”45

Three Lessons

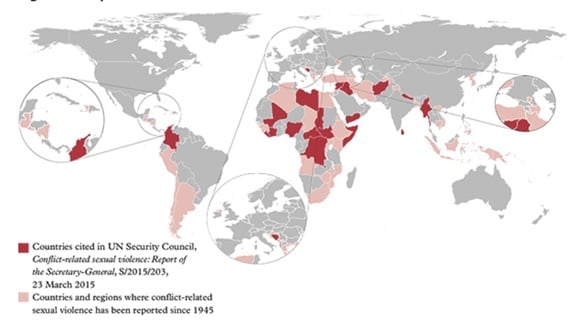

As CRSV remains a global problem (see Figure), clinicians must understand its medico-legal implications46,47,48 in light of relevant ethical, clinical, and legal lessons of history. Three are identified below.

Figure. Map of Sexual Violence in Conflict-Affected Countries

Contains Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence v 3.0 from House of Lords Select Committee on Sexual Violence in Conflict.49

Lesson 1. The first lesson is that, in common with other clinicians, physicians are integral to IHL.50,51,52 To quote Jean Pictet, a towering figure in the history of the ICRC and co-drafter of the Geneva Conventions of 1949: “International humanitarian law, whose purpose is to attenuate the evils of war, has been intimately bound from its earliest days to physicians and all others whose mission in life is to heal—the noblest of all professions.”53

During any conflict or subsequent occupation, it is all but inevitable that clinicians will be affected by IHL. In such circumstances, clinicians serving in uniform in regular armed forces will be subject to protections accorded by IHL, such as those in Chapter III (entitled “Medical Units and Establishments”) of the First Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field of 1949. They will additionally be subject to the prohibitions recognized by IHL, such as the prohibitions in each of the 4 Geneva Conventions of 1949 against “wilful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments, wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health” (Article 50 of the First Geneva Convention of 1949, Article 51 of the Second Geneva Convention of 1949, Article 130 of the Third Geneva Convention of 1949 and Article 147 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949).26 At the same time, clinicians will remain subject to the domestic law of the country they are serving, the service law applicable to the armed forces to which they are attached, and the overall military justice system connected to that service law.54 To cap it all, every clinician will remain subject to the regulatory and disciplinary systems of their specific branch of their specific profession.

With respect to whether a clinician is a combatant or noncombatant during any conflict, the relevant rules of IHL are complex and not easy to summarize in a relatively short article such as this. It suffices to quote from The Joint Service Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict, a publication of the Ministry of Defence of the UK:

Some members of the armed forces of a state (medical personnel and chaplains) are classed as non-combatants and do not have the right to take a direct part in hostilities…. The expression “medical personnel” is not confined to doctors and nurses but also embraces a wide range of specialists, technicians, maintenance staff, drivers, cooks, and administrators provided that they are exclusively assigned to the medical staff. Non-combatant members of armed forces who participate directly in hostilities may expect to forfeit that noncombatant status. They also render themselves liable to trial and punishment. Non-combatant members of the armed forces are, however, legally permitted to defend themselves against acts of violence which are directed against them and, for this purpose, the use of firearms may be justified. Medical personnel do not forfeit their protection under Geneva Convention I 1949 [ie, the First Geneva Convention of 1949] by being armed and by using those arms in their own defence or in the defence of the wounded and sick in their charge.55

Other clinicians may not be in uniform, but they may work within the health care system of the country where a conflict is unfolding or where an occupation has ensued. As such, clinicians, irrespective of whether they are members of the armed forces, must be protected by—and must respect—the prohibitions imposed by IHL; these include those recognized by each of the 4 Geneva Conventions mentioned above. Accordingly, if a clinician falls afoul of IHL, this may trigger professional disciplinary proceedings (eg, for allegedly infringing an ethical principle or regulatory rule), domestic civil proceedings (eg, for alleged negligence), criminal court or court martial proceedings (eg, for allegedly aiding and abetting a rapist) or, in exceptional circumstances, international criminal proceedings (eg, for alleged complicity in a crime against humanity or a war crime).

In this context, all clinicians should be familiar with the Doctors Trial, which formed part of the second wave of trials instituted at Nuremberg during the late 1940s. Clinicians should likewise be familiar with the lessons to be derived from the case56 and with the Nuremberg Code on Medical Experimentation, which has become synonymous with it.57 In the Doctors Trial, 23 defendants, 20 of whom were physicians, were put on trial before the US Military Tribunal. On August 20, 1947, 16 of the defendants were found guilty, with 7 of these sentenced to death.58,59 The following extract from the judgment encapsulates the essence of the case against the doctors who were found guilty:

Judged by any standard of proof the record clearly shows the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity substantially as alleged in counts two and three of the indictment. Beginning with the outbreak of World War II criminal medical experiments on non-German nationals, both prisoners of war and civilians, including Jews and “asocial” persons, were carried out on a large scale in Germany and the occupied countries. These experiments were not the isolated and casual acts of individual doctors and scientists working solely on their own responsibility, but were the product of coordinated policy-making and planning at high governmental, military, and Nazi Party levels, conducted as an integral part of the total war effort. They were ordered, sanctioned, permitted, or approved by persons in positions of authority who under all principles of law were under the duty to know about these things and to take steps to terminate or prevent them.60

The Doctors Trial, together with more recent cases involving clinicians accused of international crimes, such as Prosecutor v Elizaphan and Gérard Ntakirutimana,61 have been discussed elsewhere,62 and ought to be familiar to every clinician.

In the light of the legal history sketched out above, each case involving an allegation of CRSV against a clinician or any other person will turn on its facts, the applicable laws, the available evidence, and the critical issue of whether—and, if so, how—the wheels of justice are activated. If the wheels of domestic justice are activated in a fair manner via the criminal or military justice system of, say, the state responsible for a soldier alleged to have engaged in CRSV, the case is unlikely to reach an international criminal court. However, since its establishment in 1998, the ICC has, in theory, served as a prosecutorial and judicial backstop which can field cases where impunity is alleged to have prevailed.

In practice, but subject to the caveats mentioned elsewhere in this article, the first lesson requires every clinician to comply with the applicable laws and to adhere to medical ethics63,64,65 while staying safe66 and ensuring that an alleged victim of CRSV benefits from a holistic survivor-centered approach.67,68 As the UN warns: “Individuals must be given appropriate information to enable them to take informed decisions regarding their medical, sexual, reproductive, psychosocial, psychological, legal, and security needs, as well as their participation in justice and accountability processes.”69 To these ends, in addition to treating an alleged victim of CRSV, it is ethically appropriate for clinicians to go further by, for example, reminding the patient that they may seek—and may be entitled to—other forms of advice and support. These will invariably include independent legal advice from a suitable lawyer in addition to any available legal aid.70,71

Lesson 2. The second lesson is that during or after any conflict in which CRSV has allegedly been inflicted, a clinician may be invited or required to provide evidence to a police investigation, an official inquiry or other investigatory body, or a court. In such circumstances, the precise nature of each clinician’s involvement will be determined by the answers to various questions. Such questions include the following:

- Is the clinician a victim of CRSV, an alleged perpetrator of CRSV, an accomplice or accessory of the alleged perpetrator, a witness to an alleged act of CRSV (ie, a fact witness), an expert witness, or otherwise involved in the case?

- What is the status of the clinician—a member of a medical unit or other unit of the regular armed forces of a sovereign state, a clinician in a civilian hospital or other nonmilitary medical setting, an alleged de facto member of irregular forces or proscribed terrorist organisation, or a member of another category?

- Does the case involve an alleged crime, such as rape; an alleged civil wrong, such as an alleged act of medical negligence during the treatment of the patient; an alleged act of professional misconduct, such as a breach of patient confidentiality; or an alleged violation of constitutional or human rights for which a public body, a government or the state itself is allegedly responsible?

- In a criminal case, is the applicable law domestic criminal law, service law, domestic civil law, domestic or international human rights law, or IHL and, through that, ICL? If the case involves domestic criminal law but within a transnational setting (eg, because the alleged perpetrator is a member of the armed forces on deployment overseas), which country’s domestic criminal law applies?

- What is the identity of the state whose law enforcement authorities have acted upon an allegation of CRSV? What is the precise nature of the allegation itself? Which are the applicable rules of evidence? And, if the case is litigated, which are the relevant court procedures? Indeed, if the case does reach court and if the clinician is required to participate as, say, a fact witness, other questions will arise, not least on account of the requirements of the specific professional code of conduct binding upon the clinician and of any pertinent guidance issued by the professional or regulatory body under whose ambit the clinician falls.72,73

In turn, the second lesson underlines the indispensability of accurate, comprehensive, and contemporaneous medical records.74 It likewise highlights the ethical dilemma that may arise if a clinician is caught between, on the one hand, the duty to maintain patient confidentiality, private information, and personal data and, on the other hand, a parallel duty to comply with any court order or law requiring the release of patient details.75,76

The second lesson is not only illustrated by the testimony of the aforementioned Dr Merdžanić in the case of Stakić. It is also illustrated by the historic 2-volume report of the then European Commission on Human Rights, adopted on July 10, 1976, in the case of Cyprus v Turkey.77 In an investigation prompted by grave allegations that Turkey was responsible for, among other things, “Wholesale and repeated rapes” after Turkey had invaded the Republic of Cyprus in 1974, the commission paid particular attention to the evidence presented by two medical witnesses—Dr Kostas Hadjikakou, a doctor in the field of orthopaedic medicine, and Dr Xanthos Charalambides, a gynaecologist. In its evaluation of the evidence, the Commission was particularly impressed by the written and oral evidence that each doctor gave:

The Delegation noted that the two medical witnesses, Drs. Hadjikakou and Charalambides, endeavoured to be precise and to avoid any exaggeration. Their statements were corroborated by the other witnesses … and by the great number of written statements submitted. The Commission is therefore satisfied that the oral evidence obtained on this item is correct.77

In the Commission’s assessment, “The evidence shows that rapes were committed by Turkish soldiers and at least in two cases even by Turkish officers, and this not only in some isolated cases of indiscipline.”77 Thus, the Commission found, “by 12 votes against one,” that “the incidents of rape [identified in the Report] … and regarded as established constitute ‘inhuman treatment’ in the sense of Art. 3 of the [European] Convention [on Human Rights], which is imputable to Turkey”77,78; under Article 3 of the Convention, “No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”79 There was a clear correlation between the Commission’s conclusion and the credible evidence presented by the 2 aforementioned physicians.

Lesson 3. The third lesson is that, given developments in international human rights law (IHRL)80 and IHL81,82 since the late 1990s, the infliction of rape in any domestic or international conflict is considered not only inhuman but also capable of being equated to the commission of torture and even genocide. Accordingly, international law on rape has broadened since 1976 when, in the aforementioned case of Cyprus v Turkey, the Commission only went as far as to regard rape as inhuman.

In IHRL, the potential nexus between rape and torture was established in 1997 in Aydin v Turkey.83 This landmark case arose from the long-standing internal conflict in southeast Turkey. As confirmed by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), the case arose after “a Turkish citizen of Kurdish origin” alleged that, when aged 17, she had been raped and otherwise physically and mentally mistreated while “in detention” in Turkey at the hands of “security forces.”83 In its judgment, the ECtHR held that “the accumulation of acts of physical and mental violence inflicted on the applicant and the especially cruel act of rape to which she was subjected amounted to torture in breach of Article 3 of the Convention [prohibiting inter alia torture].” Thus, the ECtHR concluded that there had been a “violation” of Article 3 for which Turkey was responsible.83

In 1998, in the case of Prosecutor v Zejnil Delalic, the ICTY held that, for the purposes of IHL, rape could likewise amount to torture if certain specific conditions were satisfied.84,85 In another case that same year, Prosecutor v Jean-Paul Akayesu, the ICTR reached a similar conclusion86 while going even further by holding that, given the facts in that case, “rape and sexual violence … constitute genocide.”86 In the same case, the ICTR defined rape as “a physical invasion of a sexual nature, committed on a person under circumstances which are coercive.”86 The use of the word person indicates that males and females are capable of being victims of rape for the purposes of IHL. This word choice is consistent with the principle of equality before the law, which is widely considered to be a cornerstone of the rule of law.87,88,89

For the clinician, these legal realities raise at least one awkward ethical issue. On the one hand, a clinician must appreciate that the patient may simultaneously be a victim of torture and possibly even genocide.90 The patient may thus be the survivor of crimes and human rights violations, if not other illegal acts.91 Given the traumatic ordeal potentially experienced by the patient, the clinician must therefore have justice in mind while maintaining patient confidentiality and treating the patient with particular care, sensitivity, and respect for human dignity.92,93 At the same time, as already indicated above, the clinician should maintain accurate, comprehensive, and contemporaneous medical records. Subject to certain conditions being met, those notes may have to be produced as evidence before a domestic court94,95 or, in exceptional circumstances, an international court of law.96,97,98 The clinician may thereby help justice to be served. On the other hand, a clinician must approach any alleged victim of rape with a nonjudgmental open mind99 and without stepping into the shoes of a police investigator, lawyer, or judge. To that extent, the UN’s promotion of the term survivor is somewhat problematic. After all, at first sight, it appears to rest on an inappropriate assumption—that an alleged survivor of CRSV (ie, a person claiming to be a survivor) is a survivor. That is not necessarily so. Nor is it necessarily the case that an alleged perpetrator of CRSV is a perpetrator. An alleged perpetrator remains such while benefiting from the presumption of innocence until either a guilty plea or conviction following a fair process.

Albeit in a non-CRSV context, the conviction in England in 2019 of the fantasist, Carl Beech, serves as a salutary reminder that an alleged victim of a sexual crime may not necessarily be telling the truth. Before being unmasked, Beech made a string of sensational allegations about the alleged wrongdoing of prominent personalities. In turn, these allegations were widely reported by the media, echoed by parliamentarians, and, in circumstances that became intensely controversial, investigated by the police. Eventually, after evidence emerged that Beech was a fantasist, he was prosecuted and convicted of 12 counts of perverting the course of justice.100 Beech was also exposed for other reasons “after indecent images were found on his electronic devices.”100 The scale of the criminality of Beech is clear from the Sentencing Remarks issued by the judge in Newcastle Crown Court upon handing the convicted Beech a total sentence of 18 years of imprisonment.101 For the purposes of this article, it suffices to quote just the opening 2 sentences:

Between December 2012 and March 2016 you [ie, Carl Beech] deliberately, repeatedly and maliciously told lies to the police and the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority falsely claiming that, as a child between the ages of 7 and 15, you had been a victim of appalling sexual and physical abuse, had witnessed other children being similarly abused and seen three children being murdered. You falsely accused a number of well-known public figures including politicians, very senior military figures and the heads of the intelligence services, many of whom had since died but some were still alive, of having been members of paedophile groups and the perpetrators.101

For clinicians, what makes the case of R v Carl Beech particularly instructive are at least 2 factors. Firstly, the case reminds us that there may be bad apples among the ranks of ethical, honest, and otherwise professional clinicians. In the words of the judge in his Sentencing Remarks, Beech was “a trained paediatric nurse” as well as “a nursing manager before becoming a Care Quality Commission inspector,”101 the Care Quality Commission being the independent statutory regulator of health and audit social care in England. Yet, despite this professional background, which should have instilled Beech with a sense of professionalism infused with ethics, his “actions,” in the words of the Sentencing Remarks, “traduced reputations by maliciously making lurid and the most serious false allegations” that caused “distress, anger and loss … to the individuals … accused and their families, some of whom died during the process.”101 Secondly, the case of R v Carl Beech reminds us that, although an allegation of rape or sexual crime must be taken seriously and investigated effectively by the police, the allegation remains an allegation pending any lawful plea of guilt or conviction. This reminder flows from the oft-quoted observations of Mr Justice Megarry in a much earlier English case reported in 1970:

As everybody who has anything to do with the law well knows, the path of the law is strewn with examples of open and shut cases which, somehow, were not; of unanswerable charges which, in the event, were completely answered; of inexplicable conduct which was fully explained; of fixed and unalterable determinations that, by discussion, suffered a change.102

In his independent review of the Metropolitan Police Service’s handling of nonrecent sexual offence investigations alleged against persons of public prominence, Sir Richard Henriques, a retired judge of the High Court of England and Wales, was damning in his criticism of the widespread police practice of “believing” a “victim” of sexual abuse:

I understand the strategic aim of improving the Police Service response to complaints of sexual abuse and the aim to make it easier for victims of sexual abuse to make a complaint to the police. The officers steadfastly insist that the “victim must be believed during the taking of the statement.” I disagree. It is the duty of a police officer to investigate. Many decisions in the criminal justice process have to be taken on paper. The police officer taking a statement from a complainant has a unique opportunity to assess the complainant’s veracity. The effect of requiring a police officer, in such a position, to believe a complainant reverses the burden of proof. It also restricts the officer’s ability to test the complainant’s evidence.103

Hence Recommendation 2 of Sir Richard Henriques states:

The instruction to “believe a ‘victim’s’ account” should cease. It should be the duty of an officer interviewing a complainant to investigate the facts objectively and impartially and with an open mind from the outset of the investigation. At no stage must the officer show any form of disbelief and every effort must be made to facilitate the giving of a detailed account in a non-confrontational manner.103

Hence also a related warning issued by Sir Richard Henriques, which states: “In fact, nobody knows, nor can ever know, the extent of false complaints. It is critical, however, that those charged with the responsibility of investigating crime, or instructing others in that process, have in mind the real, as opposed to the remote, possibility that a complaint may be false.”103

Henriques’ review is not immaterial to clinicians. Whenever a clinician encounters a patient alleging that they are the victim of CRSV or other crime and that another named or unnamed person is the perpetrator, the clinician must maintain a nonjudgmental open mind. On the one hand, the patient may be telling the truth. On the other hand, the patient may be telling a pack of lies.

Conflict-Related Sexual Violence and Abortion

In the context of CRSV, it would be remiss of the authors not to mention the sensitive issue of abortion. After all, during or in the aftermath of any conflict, a patient may seek medical advice with the aim of terminating an unplanned pregnancy caused by an alleged rape. To that end, the victim may consult a clinician who happens to have sincere conscientious objections to abortion. In such circumstances, the clinician cannot react by burying their head in the sand. At the very least, that may amount to professional misconduct. Instead, the clinician must respond in line with the law, any applicable code of professional conduct, and any relevant ethical guidance issued by the clinician’s regulator. An example is the guidance published by the General Medical Council, the regulator of physicians in the UK, entitled “Personal Beliefs and Medical Practice.”104 Among its contents is a reminder of the provisions of paragraph 52 of “Good Medical Practice,” the code of conduct binding upon physicians in the UK:

52. You must explain to patients if you have a conscientious objection to a particular procedure. You must tell them about their right to see another doctor and make sure they have enough information to exercise that right. In providing this information you must not imply or express disapproval of the patient’s lifestyle, choices or beliefs. If it is not practical for a patient to arrange to see another doctor, you must make sure that arrangements are made for another suitably qualified colleague to take over your role.105

There is so much more to the ethico-legal dimensions of abortion,106 and this article has merely scratched the surface. The fact remains that, due to the nature of CRSV, the ethico-legal dimensions of abortion could suddenly come to the fore during any conflict or occupation. Accordingly, an individual clinician must know how to respond.

Conclusion

International law vis-à-vis CRSV has undergone a sea change since 1945—so much so that, as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization recognized on June 1, 2021, CRSV “can amount to a serious violation of International Law,” including IHL and IHRL; CRSV can likewise “amount to a crime under international criminal law and in some jurisdictions, under domestic law.”107 The sea change has also resulted in the UNSC not only embracing a holistic survivor-centered approach to CRSV but also adopting UNSC Resolution 2467.

For all of its importance, Resolution 2467 will have no practical effect unless all states ratify the core instruments of IHL, adhere to them, and enforce them. Failing that, Resolution 2467 will likewise have no practical effect unless the UNSC, the ICC, and other appropriate international bodies exercise their powers consistently in order to give practical meaning to Resolution 2467 and its call for CRSV-related impunity to come to an end.

A survivor-centered approach has profound ethical, legal, and other implications, not least of all for any clinician who is called upon to treat an alleged victim of CRSV within or beyond a conflict zone. Such a person must respond appropriately—in line with their ethical and legal duties, in the interests of the patient, and, potentially, for the sake of justice.

Postscript

On August 15, 2021, after the first draft of this article was composed, the Taliban stormed back to power in Afghanistan. On the same day, The Conversation published an article with a self-explanatory title: “The world must not look away as the Taliban sexually enslaves women and girls.”108 On the following day, the UN circulated a press release109 that summarized the findings of a new report of the UN Secretary-General, dated July 16, 2021, and entitled “Children and Armed Conflict in Afghanistan.”110 The press release echoed a message issued by Virginia Gamba, the UN Secretary-General’s special representative for children and armed conflict, who had “called for Afghanistan to uphold the criminalization of the practice of bacha bazi, a form of sexual abuse against boys, in line with revisions to the penal code in 2018.”111

Thus, even before the return of the Taliban to power in Kabul on August 15, 2021, Afghanistan was already bedevilled by CRSV and the impunity that accompanied it. Since then, fresh waves of CRSV have reportedly washed over that landlocked country.112,113 If those reports are true, the global struggle against CRSV has entered a menacing new epoch.

References

-

Lieber F; Board of Officers. Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field, General Orders No. 100. Adjutant General’s Office, War Department; April 24, 1863. US National Library of Medicine Digital Collections. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/dw/101656162/PDF/101656162.pdf

-

Gesley J. The “Lieber Code”— the first modern codification of the laws of war. Library of Congress blog. April 24, 2018. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2018/04/the-lieber-code-the-first-modern-codification-of-the-laws-of-war/

-

Farr J. Lieber, Francis (18 Mar. 1798 or 1800–02 October 1872). American National Biography. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1400365

-

Department of Defense Law of War Manual: June 2015. Office of General Counsel, US Department of Defense; 2016. Updated December 2016. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/DoD%20Law%20of%20War%20Manual%20-%20June%202015%20Updated%20Dec%202016.pdf?ver=2016-12-13-172036-190

-

Hague Conventions. International Committee of the Red Cross. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://casebook.icrc.org/glossary/hague-conventions

-

The laws of war. The Avalon Project, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/lawwar.asp

-

Van Schaack B, Slye R. A concise history of international criminal law. Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. January 1, 2007. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1629&context=facpubs

-

Schabas WA, ed. The Cambridge Companion to International Criminal Law. Cambridge University Press; 2016.

-

Becker A. The Great War: world war, total war. Int Rev Red Cross. 2015;97(900):1029-1045. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/irc_97_900-5.compressed.pdf

-

Rivière A. Rape. In: Ute D, Gatrell P, Janz O, et al, eds. International Encyclopaedia of the First World War. Freie Universität Berlin; 2015. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/rape

-

Nabti N. Legacy of impunity: sexual violence against Armenian women and girls during the Genocide. In: Demirdjian A, ed. The Armenian Genocide Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan; 2016:118-148.

-

Flaschka MJ. Race, Rape and Gender in Nazi-Occupied Territories. Dissertation. Kent State University; 2009. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=kent1258726022&disposition=inline

-

Kay AJ, Stahel D eds. Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Europe. Indiana University Press; 2018.

-

Beorn WW. Bodily conquest: sexual violence in the Nazi East. In: Kay AJ, Stahel D, eds. Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Europe. Indiana University Press; 2018:chap 9.

-

Gebhardt M. Crimes Unspoken: The Rape of German Women at the End of the Second World War. Somers N, trans. Polity; 2017

-

The Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal: Nuremberg: 14 November 1945-1 October 1946: Volume 1: Official Text in the English Language: Official Documents. International Military Tribunal; 1947:8-18. US Library of Congress. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/collections/military-legal-resources/?q=NT_major-war-criminals.html

-

Judgment: International Military Tribunal for the Far East: Part B: Annexes. US Library of Congress; 1948:31,111,113,117. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/collections/military-legal-resources/?q=pdf/Judgment-IMTFE-Vol-II-PartC-Annexes-Appendices.pdf

-

Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. January 19, 1946. Treaties and Other International Acts Series 1589. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.3_1946%20Tokyo%20Charter.pdf

-

Goldstone RJ. Prosecuting rape as a war crime. Case West Reserve J Int Law. 2002;34(3):277-285. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1461&context=jil

-

Jackson RH. Serving the administration of criminal justice: address before the Criminal Law Section of the American Bar Association, Boston. Robert H. Jackson Center. August 24, 1953. Accessed September 6, 2021. http://www.roberthjackson.org/speech-and-writing/serving-the-administration-of-criminal-justice/

-

Eboe-Osuji C. International Law and Sexual Violence in Armed Conflicts. Brill–Nijhoff; 2012

-

Brammertz S, Jarvis M, eds. Prosecuting Conflict-Related Sexual Violence at the ICTY. Oxford University Press; 2016.

-

Bouvier P. Sexual violence, health and humanitarian ethics: towards a holistic, person-centred approach. Int Rev Red Cross. 2014;96(894):565-584. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-review-of-the-red-cross/article/abs/sexual-violence-health-and-humanitarian-ethics-towards-a-holistic-personcentred-approach/3EF1FC30B03FD94C55903FA6A279C429

-

McAlpine A, Hossain M, Zimmerman C. Sex trafficking and sexual exploitation in settings affected by armed conflicts in Africa, Asia and the Middle East: systematic review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16(1):34.

- Stachow E. Conflict-related sexual violence: a review. BMJ Mil Health. 2020;166(3):183-186.

-

International Committee of the Red Cross. The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949. International Committee of the Red Cross; 1949. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/publications/icrc-002-0173.pdf

-

Pictet JS, ed. The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: Commentary: IV Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. International Committee of the Red Cross; 1958: 205. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/pdf/GC_1949-IV.pdf

-

Weaver GM. Ideologies of Forgetting: American Erasure of Women’s Sexual Trauma in the Vietnam War. Dissertation. Rice University; 2006. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/20667/3256763.PDF?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

-

Blood-stained hands: past atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan’s legacy of impunity. Human Rights Watch. July 6, 2005. Accessed September 11, 2021. http://www.hrw.org/report/2005/07/06/blood-stained-hands/past-atrocities-kabul-and-afghanistans-legacy-impunity

-

United Nations Security Council. Resolution 827 (1993). Adopted May 25, 1993. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/827(1993)

-

Security Council. Provisional verbatim record of the three thousand two hundred and seventh meeting United Nations; 1993. Accessed July 17, 2021. http://www.icty.org/x/file/Legal%20Library/Statute/930525-unsc-verbatim-record.pdf

-

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. United Nations Treaty Collection. Adopted July 17, 1998. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XVIII-10&chapter=18&clang=_en#:~:text=The%20Statute%20was%20adopted%20on,of%20an%20International%20Criminal%20Court.&text=After%20that%20date%2C%20the%20Statute,be%20until%2031%20December%202000

-

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. International Criminal Court. Adopted July 17 1998. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/RS-Eng.pdf

-

Prosecutor v. Milomir Stakić (Trial Judgement), Case No. IT-97-24-T (ICTY 2003). Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.icty.org/en/case/stakic/tjug/en/stak-tj30731e.pdf

-

Prosecutor v. Milomir Stakić (Appeals Chamber Judgement), Case No. IT-97-24-A (ICTY 2006). Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.icty.org/x/cases/stakic/acjug/en/sta-aj060322e.pdf

-

Dr. Idriz Merdžanić. International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.icty.org/en/content/dr-idriz-merd%C5%BEani%C4%87

-

Health-care providers, patients suffer thousands of attacks on health-care services over the past five years ICRC data shows. News release. International Committee of the Red Cross; May 3, 2021. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://www.icrc.org/en/document/health-care-providers-patients-suffer-thousands-attacks-health-care-services-past-5-years

-

Principles of medical ethics relevant to the role of health personnel, particularly physicians, in the protection of prisoners and detainees against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. General Assembly resolution 37/194. UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Adopted December 18, 1982. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/principles-medical-ethics-relevant-role-health-personnel

-

Ethical decision-making for doctors in the armed forces: a tool kit. Guidance from the BMA Medical Ethics Committee and Armed Forces Committee. British Medical Association; 2012. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/1218/bma-armed-forces-toolkit-oct-2012.pdf

-

Review of the sexual violence elements of the judgments of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and the Special Court for Sierra Leone in the light of Security Council 1820. United Nations. 2010. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/files/Review%20of%20the%20Sexual%20Violence%20Elements%20in%20the%20Light%20of%20the%20Security-Council%20resolution%201820.pdf

-

Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict. Secretary-General annual reports. United Nations. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/digital-library/reports/sg-reports/

-

Chinkin C, Rees M. Commentary on Security Council Resolution 2467: continued state obligation and civil society action on sexual violence in conflict. London School of Economics and Political Science; 2019. Accessed July 17, 2021. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/103210/1/Chinkin_commentary_on_Security_Council_Resolution_2467_published.pdf

-

United Nations Security Council. Resolution 1820 (2008). Adopted June 19, 2008. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/1820(2008)

-

United Nations Security Council. Resolution 2467 (2019). Adopted April 23, 2019. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N19/118/28/PDF/N1911828.pdf?OpenElement

-

Landmark UN Security Council Resolution 2467 (2019) strengthens justice and accountability and calls for a survivor-centered approach in the prevention and response to conflict-related sexual violence. News release. Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, United Nations; April 29, 2019. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/press-release/landmark-un-security-council-resolution-2467-2019-strengthens-justice-and-accountability-and-calls-for-a-survivor-centered-approach-in-the-prevention-and-response-to-conflict-related-sexual-violence/

-

Sexual and gender-based violence. Doctors Without Borders. Accessed July 18, 2021. https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/what-we-do/medical-issues/sexual-and-gender-based-violence

-

Sexual violence. Doctors Without Borders. Accessed July 18, 2021. https://fieldresearch.msf.org/discover?scope=10144%2F10833&query=Sexual+violence&submit=

-

Sexual and Gender Based Violence: A Handbook for Implementing a Response in Health Services Towards Sexual Violence. Médecins Sans Frontières; 2011.

-

Sexual Violence in Conflict: A War Crime. Report of Session 2015-2016. House of Lords Select Committee on Sexual Violence in Conflict; 2016:25. HL 123.Accessed January 20, 2021. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201516/ldselect/ldsvc/123/123.pdf

- Leaning J. Medicine and international humanitarian law: law provides norms that must guide doctors in war and peace. British Med J. 1999;319(7207):393-394.

-

IHL database: customary IHL. Rule 25. Medical personnel. International Committee of the Red Cross. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_rul_rule25

-

Lewis DA, Modirzadeh NK, Blum G. Medical Care in Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law and State Responses to Terrorism. Harvard Law School Program on International Law and Armed Conflict; 2015. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/22508590/HLS_PILAC_Medical_Care_in_Armed_Conflict_IHL_and_State_Responses_to_Terrorism_September_2015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

-

Pictet J. The medical profession and international humanitarian law. Int Rev Red Cross. 1985;25(247):191-209. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/medical-profession-and-international-humanitarian-law

-

Collection: manual of service law. Gov.UK. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/manual-of-service-law-msl

-

The Joint Service Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict. Ministry of Defence; 2004:38. JSP 383. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/27874/JSP3832004Edition.pdf

-

Annas GJ, Grodin MA. Medical ethics and human rights: legacies of Nuremberg. Hofstra Law Policy Symp. 1999:3(11):111-123. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlps/?utm_source=scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu%2Fhlps%2Fvol3%2Fiss1%2F11&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

-

Nuremberg Code: directives for human experimentation. ORI introduction to RCR: chapter 3. The protection of human subjects. Office of Research Integrity, US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://ori.hhs.gov/content/chapter-3-The-Protection-of-Human-Subjects-nuremberg-code-directives-human-experimentation

-

The Doctors Trial: the medical case of the subsequent Nuremberg proceedings. US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-doctors-trial-the-medical-case-of-the-subsequent-nuremberg-proceedings

-

Nuremberg Code. US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://www.ushmm.org/information/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/special-focus/doctors-trial/nuremberg-code

-

Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No. 10: Volume II [“The Medical Case” and “The Milch Case”]: Nuernberg October 1946-April 1949. US Government Printing Office; undated, 151. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.uni-marburg.de/de/icwc/dokumentation/dokumente/nmt/nt_war-criminals_vol-ii.pdf

-

Ntakirutimana et al (ICTR 96-17). United Nations International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://unictr.irmct.org/en/cases/ictr-96-17

-

Mehring S. Medical war crimes. In: von Bogdandy A, Wolfrum R, eds. Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law. Max-Planck Institute; 2011:229-279. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.mpil.de/files/pdf3/mpunyb_05_Sigrid_Mehring_151.pdf

-

Common ethical principles of health care in conflict and other emergencies. International Committee of the Red Cross. June 30, 2015. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://www.icrc.org/en/document/common-ethical-principles-health-care-conflict-and-other-emergencies

-

Medical ethics/medical duties. International Committee of the Red Cross. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://casebook.icrc.org/glossary/medical-ethics-medical-duties

-

The practical guide to humanitarian law. Médecins Sans Frontières. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://guide-humanitarian-law.org/content/article/3/medical-ethics/

-

HCID initiative. Health Care in Danger. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://healthcareindanger.org/hcid-project/

-

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Protection of victims of sexual violence: lessons learned. Workshop report. United Nations; 2019. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/ReportLessonsLearned.pdf

-

Downing C, Van Broeckhoven K, O’Neil S. New data underscores urgent need for holistic approaches to conflict-related sexual violence. University Centre for Policy Research, United Nations; 2021. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://cpr.unu.edu/publications/articles/holistic-approaches-crsv.html

-

Department of Peace Operations. Handbook for United Nations Field Missions on Preventing and Responding to Conflict-Related Sexual Violence. United Nations; 2020:16. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/United%20Nations_CRSV%20Handbook.pdf

-

Guidance note of the Secretary-General: reparations for conflict-related sexual violence. United Nations; 2014. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Press/GuidanceNoteReparationsJune-2014.pdf

-

Muwanga S, Traoré D, Chekir H, Tsuga A. The Impact of Litigation on Combating Sexual Violence and its Consequences in Africa: Sharing Experience and Practical Advice. International Federation for Human Rights; 2019. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/fidh-lhr_compendium_impact_of_litigation_on_combating_sgbv_in_africa_nov2019.pdf

-

American Medical Association. Opinion 9.7.1 Medical testimony. Code of Medical Ethics. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/medical-testimony

-

Doctors giving evidence in court. UK General Medical Council. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/protecting-children-and-young-people/doctors-giving-evidence-in-court

-

Ribeiro SF, van der Straten Ponthoz D. International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict Best Practice on the Documentation of Sexual Violence as a Crime or Violation of International Law. 2nd ed. UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office; 2017. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/598335/International_Protocol_2017_2nd_Edition.pdf

-

Confidentiality: good practice in handling patient information: disclosing patients’ personal information: a framework. UK General Medical Council. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/confidentiality/disclosing-patients-personal-information-a-framework

-

Acting as a witness in legal proceedings. UK General Medical Council. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/acting-as-a-witness/acting-as-a-witness-in-legal-proceedings

-

European Commission of Human Rights Applications Nos. 6780/74 and 6950/75: Cyprus Against Turkey. Report of the Commission. Vol 1. Adopted July 10, 1976. Council of Europe; 1979. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.stradalex.com/en/sl_src_publ_jur_int/document/echr_6780-74_001-142540

-

European Commission of Human Rights. Applications Nos. 6780/74 and 6950/75: Cyprus Against Turkey. Report of the Commission. Vol 2. Adopted July 10, 1976. Council of Europe; 1979. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.stradalex.com/en/sl_src_publ_jur_int/document/echr_6780-74_001-142541

-

European Court of Human Rights. European Convention on Human Rights as amended by Protocols Nos. 11, 14, and 15 and supplemented by Protocols Nos. 1, 4, 6, 7, 12, 13, and 16. Council of Europe; 2021. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf

- McGlynn C. Rape, torture and the European Convention on Human Rights. Int Comp Law Q. 2009;58(3):565-595.

-

IHL and human rights law. International Committee of the Red Cross. October 29, 2010. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/war-and-law/ihl-other-legal-regmies/ihl-human-rights/overview-ihl-and-human-rights.htm#:~:text=Both%20international%20humanitarian%20law%20and%20human%20rig9ts%20law,in%20Article%205%20to%20the%20Fourth%20Geneva%20Convention%29

-

What is the difference between IHL and human rights law? International Committee of the Red Cross. January 22, 2015. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://www.icrc.org/en/document/what-difference-between-ihl-and-human-rights-law

-

Aydin v Turkey, Case No. 57/1996/676/866 (ECHR 1997). Accessed July 17, 2021. https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-58371%22]}

-

Prosecutor v Zejnil Delalic, Zdravko Mucic, Hazim Delic and Esad Landzo (Trial Judgement), Case No. IT-96-21-T (ICTY 1998). Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.icty.org/x/cases/mucic/tjug/en/981116_judg_en.pdf

-

Prosecutor v Zejnil Delalic, Zdravko Mucic, Hazim Delic and Esad Landzo (Appeals Chamber Judgement), Case No. IT-96-21-A (ICTY 2001). Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.icty.org/x/cases/mucic/acjug/en/cel-aj010220.pdf

-

The Prosecutor v. Jean-Paul Akayesu (Trial Judgement), Case No. ICTR-96-4-T(ICTR, 1998). Accessed July 17, 2021. https://unictr.irmct.org/sites/unictr.org/files/case-documents/ictr-96-4/trial-judgements/en/980902.pdf

-

Bingham T. The Rule of Law. Penguin; 2010.

-

Venice Commission of the Council of Europe. Rule of law checklist. Adopted March 11-12, 2016. Accessed September 11, 2021. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://www.venice.coe.int/images/SITE%20IMAGES/Publications/Rule_of_Law_Check_List.pdf

-

What is rule of law? United Nations. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/what-is-the-rule-of-law/

- Eboe-Osuji C. Rape as genocide: some questions arising. J Genocide Res. 2007;9(2):251-273.

-

Gaggioli G. Sexual violence in armed conflicts: a violation of IHL and human rights law. Int Rev Red Cross. 2014;96(894):503-538. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/F14982FBF972DE4A86D8399695154FD5/S1816383115000211a.pdf/sexual_violence_in_armed_conflicts_a_violation_of_international_humanitarian_law_and_human_rights_law.pdf

-

World Health Organization. Guidelines for Medico-Legal Care for Victims of Sexual Violence. World Health Organization. 2003. Accessed July 17, 2021. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42788/924154628X.pdf?sequence=1

-

Cohen J, Green P; Healthcare Professionals Who Work With Victims of Torture Working Group. Summary quality standards for healthcare professionals working with victims of torture in detention. Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine; 2019. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://fflm.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/HWVT_summary_May-2-2019-published.pdf

-

Davis J. Collection of medical records: a primer for attorneys. American Bar Association. May 25, 2016. American Bar Association. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/products-liability/practice/2016/collection-medical-records-primer-attorneys/

-

Guidelines for releasing patient information to law enforcement. American Hospital Association. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.aha.org/standardsguidelines/2018-03-08-guidelines-releasing-patient-information-law-enforcement

-

Ngane SN. The Position of Witnesses Before the International Criminal Court. Brill; 2015.

-

War Crimes Research Office. Witness proofing at the International Criminal Court. American University Washington College of Law; 2009. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.wcl.american.edu/impact/initiatives-programs/warcrimes/our-projects/icc-legal-analysis-and-education-project/reports/report-7-witness-proofing-at-the-international-criminal-court/

-

Witnesses. International Committee of the Red Cross. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.icc-cpi.int/about/witnesses

- Kennedy, KM. What can GPs do for adult patients disclosing recent sexual violence. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(630):42-44.

-

UPDATED: how the CPS proved the case against serial liar "Nick" over false claims of VIP child abuse ring. UK Crown Prosecution Service. July 26, 2019. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://www.cps.gov.uk/cps/news/updated-how-cps-proved-case-against-serial-liar-nick-over-false-claims-vip-child-abuse

-

Regina v Carl Beech sentencing remarks. Judiciary of England and Wales, 2019. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/BEECH-Sentencing-Remarks-26.7.19-003.pdf

-

Judgement: Moss v The Queen. From the Court of Appeal of the Commonwealth of the Bahamas before Lord Mance, Lord Wilson, Lord Reed, Lord Hughes, Lord Toulson. Judgment delivered by Lord Hughes on 13 November 2013. Heard on 22 October 2013. Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.jcpc.uk/cases/docs/jcpc-2010-0021-judgment.pdf

-

Henriques R. The Independent Review of the Metropolitan Police Service’s Handling of Non-recent Sexual Offence Investigations Alleged Against Persons of Public Prominence. Metropolitan Police; 2019. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/foi-media/metropolitan-police/other_information/corporate/mps-publication-chapters-1---3-sir-richard-henriques-report.pdf

-

Personal beliefs and medical practice. UK General Medical Council. March 25, 2013. Updated April 7, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/personal-beliefs-and-medical-practice/personal-beliefs-and-medical-practice

-

Good medical practice. UK General Medical Council. March 25, 2013. Accessed January 25, 2022. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice---english-20200128_pdf-51527435.pdf

- Sawicki NN. The conscience defense to Malpractice. Calif Law Rev. 2020;108(4):1255-1316.

-

NATO policy on preventing and responding to conflict-related sexual violence. North Atlantic Treaty Organization; 2021. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2021/6/pdf/210601-CRSV-Policy.pdf

-

Narain V. The world must not look away as the Taliban sexually enslaves women and girls. Conversation. August 15, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://theconversation.com/the-world-must-not-look-away-as-the-taliban-sexually-enslaves-women-and-girls-165426

-

Report details grave violations against children in Afghanistan. UN News. August 16, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/08/1097902

-

Security Council. Children and armed conflict in Afghanistan: report of the Secretary-General. United Nations; 2021. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2021/662&Lang=E&Area=UNDOC

-

Niland N. Impunity and insurgency: a deadly combination in Afghanistan. Int Rev Red Cross. 2010;92(880):931-950. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/irrc-880-niland.pdf

-

Afghanistan: Gay man in Kabul "raped and beaten" by Taliban after being tricked into meeting. ITV News. August 28, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.itv.com/news/2021-08-28/being-gay-in-afghanistan-the-taliban-raped-him-and-beat-him

-

"Shot, raped and tortured": horrors for stranded Afghans revealed as PM confirms 311 left behind. ITV News. September 6, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.itv.com/news/2021-09-05/johnson-to-defend-his-handling-of-the-afghanistan-crisis-to-mps