Abstract

Without training in how to identify and relieve pain and suffering, surgeons miss opportunities to offer palliative services to patients. Despite explicit calls for expanding palliative care education since the 1990s, palliative care training in surgical curricula is often limited to end-of-life discussions. A growing consensus among palliative care experts suggests that formal palliative care education during surgical training should include structured communication and prognostication tools, strategies for symptom management, and an understanding of palliative care specialists’ role in treating patients at all disease stages.

The physician should not treat the disease but the patient who is suffering from it.

Moses Maimonides, Treatise on Asthma

Stop Avoiding Difficult Conversations

Surgical palliative care refers to efforts “to relieve physical pain and psychological, social, and spiritual suffering while supporting the patient’s treatment goals and respecting the patient’s racial, ethnic, religious, and cultural values.”1 Surgeons have practiced palliative care for patients for centuries. Coronary bypass, for example, relieved chest pain before physicians fully understood its life-sustaining role.2 Although the relief of suffering has motivated surgical developments and innovations, clinicians’ ability to communicate palliative intent to their patients has not always been a priority in US medical and surgical education. A study of Chicago physicians in the 1960s found that nearly 90% of clinicians surveyed preferred not to disclose a cancer diagnosis for fear that the information would have “disturbing psychological effects.”3 Because clinicians did not acknowledge the reality of death in terminal cases, patients and their families were unable to receive the support they needed. To confront this history of avoidance and integrate palliative care appropriately into surgical practice, the American College of Surgeons released its 2005 Statement of Principles of Palliative Care,1 which states: “the tradition and heritage of surgery emphasize that the control of suffering is of equal importance to the cure of disease [italics added].” Training to help clinicians identify and meet their patients’ palliative needs at all stages of disease must be robustly integrated into a system that has too long avoided or minimized them.

Curriculum Development

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the Surgical Council on Resident Education (SCORE) have included palliative care material and educational requirements in residency training since the early 2000s.4 These requirements aim to address needs of patients at all stages of disease, not just at the end of life. 2020 ACGME requirements state: “residents must learn to communicate with patients and families to partner with them to assess their care goals, including, when appropriate, end-of-life goals.”5 Similarly, the 2020 SCORE autodidactic module on Geriatric Surgery and End of Life Care broadens palliative care to include (1) advance directives and do-not-resuscitate and power of attorney orders, (2) frailty, (3) goal setting with elderly patients and families, (4) palliative and hospice care, and (5) perioperative management of geriatric patients.6 The American College of Surgeons also produced a workbook for surgical residents,7 and hospice and palliative care is now a recognized subspecialty of the American Board of Surgery.8

These initiatives aimed to create a common educational foundation, but their adoption has been inconsistent and has left many surgical trainees ill-prepared to palliate symptoms of advanced illnesses.9 Some institutions limit palliative care training to self-instructed or classroom-based curricula, while others have dedicated multidisciplinary palliative care rotations.10 Barriers to implementation vary but are likely limited by institutional expertise, absence of interdisciplinary partnerships, and the misperception that palliative care is limited to the end of life.11 As a result, data on palliative care training’s efficacy tend to derive from single-site studies.12 Nonetheless, even one multisite survey of surgery residents and faculty demonstrates a need for education that is specific, practical, and appropriate because “while many residents felt that they had appropriate clinical exposure to palliative care principles, over half of the residents felt that their education had not been appropriate for their level of training.”13 Training in communicating outcomes and prognoses, symptom management, and consultation prepare clinicians to identify and address a patient’s palliative needs.

Communicating Outcomes and Prognosis

Clinicians who are unable or unwilling to discuss potential outcomes with patients or families might unwittingly practice medicine incongruently with patients’ care goals.14 Incongruence results in unwanted procedures and generates emotional and psychological trauma. A classic example is a frail elder who requires emergent surgical intervention. While a procedure is technically possible, operating presents a high likelihood of prolonged intubation, intensive care, rehabilitation, or death. Focus groups of elders facing these scenarios reveal that maintaining independence and quality of life are paramount values in their decision making.15

Patients presented with a choice between “life or death” often agreed with aggressive treatments, even if the most likely outcome was severe disability or death.

Although it is impossible to predict a patient’s course exactly, clinician experience and prognostic tools, such as the American College of Surgeons’ NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator, can help facilitate potential outcome discussions.16 Regardless of prognostic data availability, how clinicians communicate outcomes matters. For example, in one study, patients presented with a choice between “life or death” often agreed with aggressive treatments, even if the most likely outcome was severe disability or death.15 Nevertheless, many patients asserted that quality of life should inform medical decision making for elderly patients.15 Eliciting goals of care and communicating potential outcomes can be especially challenging in situations in which there is no preexisting therapeutic relationship between a patient and surgeon. In these circumstances, best- and worst-case scenario planning offers a framework for high-stakes discussion and decision making.17 Applying this framework helps clinicians identify and uphold patient and caregiver goals of care, but it requires practice, empathy, patience, and time.

One option to address surgeon time constraints is to include surgical palliative care in clinic settings where there can be more interaction, engagement, and discussion. However, outpatient palliative discussions are rare in surgical training.13 Incorporating palliative care into the clinic has its own obstacles (eg, financial compensation, resource allocation, and clinicians’ willingness to engage), which can cause clinicians to bypass palliative needs altogether or directly refer patients to palliative care specialists. Recently, however, initiatives such as sending patients palliative care-based questions prior to their clinic visits have been shown to increase the number of questions patients ask their surgeon during the consultation.18

Current data on training residents in communication skills suggest that passive written or oral presentations are valuable in supporting in-person role-playing, feedback, and small-group discussion.10 When part of a palliative care curriculum, rotations with a palliative care team or on services with a high demand for palliative care—such as intensive care units, trauma, or surgical oncology—allow for case-based practice. Currently, however, palliative care-specific rotations are neither mandated nor universally offered in surgical training programs.

Symptom Management

According to Surgical Palliative Care: A Resident's Guide, comprehensive palliative care education means cultivating comfort in managing common distressing physical and psychological symptoms (eg, pain, dyspnea, delirium, depression, nausea, and constipation).7 Surgical trainees should also be familiar with fatigue and with inadequate oral nutrition intake and the role of artificial nutrition in its rectification. Although workbooks and other initiatives can improve clinician familiarity with these symptoms and conditions, there is little consensus about how to incorporate lessons into clinical practice.10,12

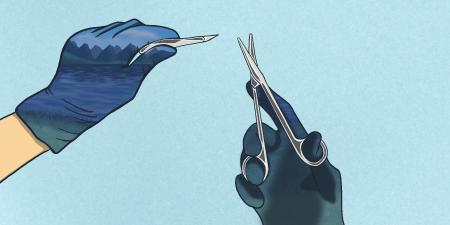

In addition to medical and pharmaceutical interventions for symptom management, surgical palliative care training should include procedures that relieve symptoms, minimize distress, and improve quality of life. Surgeons play central roles in interdisciplinary approaches to advanced illness by broadening palliative options available to patients. From removing painful spinal metastases to bypassing an obstructive intestinal tumor, surgeons can alleviate suffering in persons with advanced illnesses.19,20,21

Surgical residency should also include training in palliative procedures done with intent to relieve symptoms, minimize patient distress, and improve quality of life.22 A 2002 survey of surgical oncologists noted that patient reluctance to undergo a procedure, health insurance limitations, and lack of referrals from nonsurgical clinicians were key barriers to surgeons offering procedures.23 Additionally, depending on patient selection, palliative procedures can have high complication rates that might deter some surgeons from including them in their practice.22 Measuring surgical procedural success in terms of symptom relief and defining which patients benefit from specific interventions remain research priorities.24

When to Consult a Specialist

Because specialty palliative care involves learning to manage refractory symptoms and to coordinate complex care demands, distinguishing between primary and specialty palliative care is essential. First, this distinction acknowledges that there are not enough palliative care specialists to address all surgical patients’ unmet needs for palliative care. Second, surgeons are less likely than other clinicians to refer patients to palliative care specialists, even though many patients would likely benefit.24,25 Surgeons’ reasons for waiting too long to integrate palliative care or not integrating palliative care at all range from a surgical rescue culture—inspired by the apparent desire to do everything possible to maintain biological life—to concerns about error and responsibility.24 When a surgeon’s goal should transition from cure to palliation is a source of reasonable disagreement among reasonable clinicians, but, in all cases, a surgeon’s ability to communicate prognoses and palliative options, manage symptoms, and identify and meet patients’ palliative needs can significantly influence patients’ lives and the quality of their care.

References

-

Task Force on Surgical Palliative Care; Committee on Ethics. Statement of principles of palliative care. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2005;90(8):34-35.

- Melly L, Torregrossa G, Lee T, Jansens JL, Puskas JD. Fifty years of coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(3):1960-1967.

-

Oken D. What to tell cancer patients. A study of medical attitudes. JAMA. 1961;175:1120-1128.

- Mosenthal AC, Weissman DE, Curtis JR, et al. Integrating palliative care in the surgical and trauma intensive care unit: a report from the Improving Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit (IPAL-ICU) Project Advisory Board and the Center to Advance Palliative Care. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1199-1206.

-

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements (residency). Updated 2020. Accessed Nov 2, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf

-

Surgical Council on Resident Education. Curriculum outline for general surgery, 2020-2021. Accessed November 20, 2020. http://files.surgicalcore.org/2020-2021_GS_CO_Booklet_v3editsfinal.pdf

-

Dunn GP, Martensen R, Weissman D. Surgical Palliative Care: A Resident’s Guide. American College of Surgeons; 2009. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/education/palliativecare/surgicalpalliativecareresidents.ashx

-

Definitions of ABS specialties. American Board of Surgery. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?public_definitions

-

Wancata LM, Hinshaw DB, Suwanabol PA. Palliative care and surgical training: are we being trained to be unprepared? Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):32-33.

- Kapadia MR, Lee E, Healy H, Dort JM, Rosenbaum ME, Newcomb AB. Training surgical residents to communicate with their patients: a scoping review of the literature. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):440-449.

- Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(3):224-239.

- Bakke KE, Miranda SP, Castillo-Angeles M, et al. Training surgeons and anesthesiologists to facilitate end-of-life conversations with patients and families: a systematic review of existing educational models. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(3):702-721.

- Bonanno AM, Kiraly LN, Siegel TR, Brasel KJ, Cook MR. Surgical palliative care training in general surgery residency: an educational needs assessment. Am J Surg. 2019;217(5):928-931.

- Cooper Z, Courtwright A, Karlage A, Gawande A, Block S. Pitfalls in communication that lead to nonbeneficial emergency surgery in elderly patients with serious illness: description of the problem and elements of a solution. Ann Surg. 2014;260(6):949-957.

- Nabozny MJ, Kruser JM, Steffens NM, et al. Constructing high-stakes surgical decisions: it’s better to die trying. Ann Surg. 2016;263(1):64-70.

-

Surgical Risk Calculator. National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, American College of Surgeons. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://riskcalculator.facs.org/RiskCalculator/

- Kruser JM, Taylor LJ, Campbell TC, et al. “Best Case/Worst Case”: training surgeons to use a novel communication tool for high-risk acute surgical problems. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(4):711-719.e5.

- Schwarze ML, Buffington A, Tucholka JL, et al. Effectiveness of a question prompt list intervention for older patients considering major surgery: a multisite randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;155(1):6-13.

- Hirabayashi H, Ebara S, Kinoshita T, et al. Clinical outcome and survival after palliative surgery for spinal metastases: palliative surgery in spinal metastases. Cancer. 2003;97(2):476-484.

- Paul Olson TJ, Pinkerton C, Brasel KJ, Schwarze ML. Palliative surgery for malignant bowel obstruction from carcinomatosis: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(4):383-392.

- Roland NJ, Bradley PJ. The role of surgery in the palliation of head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;22(2):101-108.

- Miner TJ, Cohen J, Charpentier K, McPhillips J, Marvell L, Cioffi WG. The palliative triangle: improved patient selection and outcomes associated with palliative operations. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):517-522.

- McCahill LE, Krouse RS, Chu DZ, et al. Decision making in palliative surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195(3):411-413.

- Lilley EJ, Cooper Z, Schwarze ML, Mosenthal AC. Palliative care in surgery: defining the research priorities. Ann Surg. 2018;267(1):66-72.

- Bateni SB, Canter RJ, Meyers FJ, Galante JM, Bold RJ. Palliative care training and decision-making for patients with advanced cancer: a comparison of surgeons and medical physicians. Surgery. 2018;164(1):77-85.