Abstract

Health consequences of social isolation and loneliness include worsened morbidity and mortality. Despite wide recognition of this fact, little is understood about how to intervene successfully. “Social prescribing” is one approach by which clinicians can intervene on social determinants of health, which include social isolation and loneliness. This commentary on a case defines social prescribing and suggests how to integrate it into practice.

Case

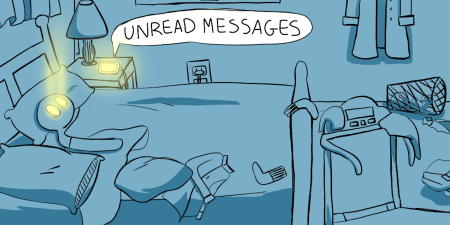

Dr J is a family medicine physician who has become aware of greater frequency and severity of physical and psychological symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, treatment resistance, poor sleep, abnormal blood pressure) in patients who are socially isolated. Dr J notices that these symptoms occur in a wide range of patients, including aging patients in residential care facilities, adolescents struggling to find friends, single parents, and recent immigrants. During encounters with patients, Dr J observes that some symptoms improve when patients interact more with fellow community members. But Dr J struggles to help enhance patients’ social connectedness via actionable care plans that have measurable health outcomes. Dr J wonders how to proceed in a clinically rigorous way.

Commentary

The phenomenon described in this case is commonly encountered by clinicians and increasingly identified as social isolation and loneliness, which can occur throughout a patient’s lifespan.1,2 Social isolation and loneliness are related but distinct: social isolation is an objective measure defined as a complete or near-complete lack of contact with society3 and loneliness is a subjective feeling of being alone, which can be experienced even when an individual is surrounded by others.4 In one study, 43% of Americans over age 60 reported feeling lonely (defined as reporting one of the loneliness items at least some of the time) and 18% reported feeling socially isolated at least some of the time.5 Loneliness and social isolation can co-occur, but each is typically measured separately.

Both loneliness and social isolation can have adverse health effects. Loneliness is associated with cardiovascular disease,6 functional decline, worse sleep and health behaviors,7,8,9 and increased risk of death.5 Similarly, social isolation is associated with coronary heart disease,10 cognitive impairment,11 functional decline,12 and poorly controlled diabetes.13 Moreover, the strength of the association between social isolation and mortality is comparable to that between cigarette smoking or obesity—2 risk factors widely recognized as health threats in public health campaigns—and mortality.14 We suggest that “social prescribing” to mitigate negative downstream effects of loneliness should be a clinical and public health priority. Ultimately, “treating” social isolation and loneliness could improve patients’ overall health and quality of life.2

Yet clinicians like Dr J have not traditionally had a framework by which to assess their patients’ social connectedness. More commonly, physicians rely on social workers (when available) to refer patients to known or available social programs. We suggest, however, that there is a need for a structured framework that physicians can use to assess patients’ social needs as a basis for reliably and routinely responding with what we describe as “social prescribing.”

Social Prescribing

Social prescribing is a systematic approach to addressing patients’ social needs by referring them to or implementing community-based interventions and facilitating social connection based on individual need.15 One goal of social prescribing is to address the social determinants of an individual patient’s loneliness, given their available resources. Social prescribing can be initiated by any member of the patient’s care team and need not be done exclusively by physicians. Ultimately, social prescribing is most successful when clinicians consider a patient’s individual needs and incorporate them in shared decision making with that patient about a prescription’s costs and benefits. For example, an individualized approach to a social prescription for a new immigrant might incorporate interventions that account for language barriers and cultural needs specific to forging social connection within their particular community. Alternatively, an older adult with limited mobility might need home-based virtual activities (popularized during the pandemic) and telephone-based companionship programs, in addition to needing a clinician who could help identify opportunities to improve mobility.16 In both examples, clinicians’ awareness of local community programs and resources available to each patient, as well as local demographics, is key to successful social prescribing. We encourage clinicians to involve all team members when considering what it means for a patient to achieve a “best fit” for a social intervention.17

Social Prescribing Framework

Here, we propose a 4-step framework to help clinicians with social prescribing.

Distinctions and drivers. Clinicians must first identify whether and to what extent the patient experiences loneliness, social isolation, or both and then evaluate those experiences’ severity, frequency, and potential contributing factors. Just as clinicians use Patient Health Questionnaires-9 to assess depression,18 so they might use tools to assess loneliness. One such tool is the UCLA-3-Item Loneliness Scale, which is highly reliable and correlates with other measures of loneliness and of health and well-being.19 The scale produces a score from 3 to 9 points, with at least 4 points representing occasional loneliness and at least 6 points representing frequent loneliness.5 Although there is no consensus on which measure to use for social isolation, commonly used scales in the United States include the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index and the Duke Social Support Index.2

Clinicians’ awareness of local community programs and resources available to each patient, as well as local demographics, is key to successful social prescribing.

After assessing a patient with an established tool, a clinician should engage in more in-depth questioning to determine how to tailor an intervention based on specific factors contributing to an individual’s social needs. These include structural features (eg, marital status or social network size) and functional features (eg, emotional or informational support) of social relationships, as well as the perceived quality of social relationships.14 For example, a clinician might start by asking the patient about recent loss (structural) or experiences of loneliness (functional). Awareness of demographic and clinical subgroups at risk for loneliness and isolation might inform more targeted assessments. Lack of instrumental support following partner loss, for instance, is related to increased loneliness.20

Goals. Focusing on known risk factors for loneliness (eg, living arrangements, social support14) aids prevention, and regular reassessment of patients already experiencing loneliness (using the tools listed above) aids intervention and management.21 We suggest offering social interventions to all who are lonely, regardless of loneliness severity. Dr J, for example, has patients expressing feelings of loneliness, so social prescribing should aim to treat loneliness, and assessment and monitoring should be routine follow-up.

Collaboration. Critical steps in social prescribing are identifying available and effective interventions, whether the patient wants help, and how to share decision making with a patient about an intervention type. Addressing social isolation or loneliness does not always require a referral to a community-based social program; it might involve creative engagement with family or considering how patients might enhance their participation in social activities.22 Some patients might just want to share their experience of loneliness and might not want clinical intervention. For other patients, community partners, counselors, health navigators, link-workers (coordinators between health care organizations and community programs), nurse practitioners, occupational therapists, physician assistants, psychologists, social workers, and kindred colleagues might be recruited to help investigate the drivers of loneliness or social isolation. In some cases, interprofessional collaboration is critical23,24,25 and can reduce the burden on physicians.26 For example, interprofessional clinic staff might integrate assessment for social connection into previsit screens with patients, provide supportive counseling, and help address patients’ coexisting psychosocial needs.

Funding social prescribing. Unlike in single-payer health care systems or in countries with robust social initiatives, social prescribing is largely excluded from payment models in the United States.27 Some for-profit programs are fee based and inaccessible to patients with low incomes, who are at higher risk of social isolation and loneliness28 and their negative health outcomes.

Interventions and Evidence

Because there might be ceiling effects of current assessment and measurement tools, a patient’s score on a standard tool might not change, despite the patient reporting feeling more social connection. If, on a more holistic assessment, social prescribing is indicated, clinicians should use evidence-based interventions whenever possible. Evidence of the efficacy of social prescribing is largely derived from single-payer health care systems in which social prescribing protocols are already in place.27 Just because an intervention lacks evidential support should not be taken to mean that clinicians should do nothing if a patient expresses a desire to feel more connected. Clinicians might work to improve a patient’s social connectedness through peer mentorship, which has been shown to reduce loneliness and decrease barriers to socializing.22 In addition, there is promising evidence of the efficacy of interventions such as befriending or peer mentoring,22 phone-based support,29 cognitive-behavioral therapy,30 animal-based therapy,21 and leisure or hobby-based interventions.31 Some social prescribing programs not only improve patients’ anxiety and depressive symptoms,32 but also reduce the number of general practitioner consultations.33 In addition, social prescribing has been found to be effective in reducing social isolation in the short-term,34,35 increasing self-confidence, and improving management of long-term conditions, self-reported physical health, and perceptions of resilience.35 Patients33 and clinicians36 tend to have positive feelings about and value social prescribing, even when consistent engagement in programs is challenging.37

Conclusion

There is a need to grow the evidence base for social prescribing in the United States and to improve understanding of how social prescribing can be integrated into clinical workflows.38 More research is needed on utilization and health outcomes of social prescribing. Evidence of effective social interventions in the United States is limited to older adults,39 but some evidence suggests that social interventions might be effective in decreasing loneliness in people aged 25 and younger.40 With regard to workflows, the role of link workers is essential for successful implementation of social programs,41,42 since link workers bridge health care organizations by implementing community programs, supporting patients, and helping maintain patient participation after finding a best-fit program.24,34,43

When clinicians prescribe a new medication for a patient, they must consider a wide variety of factors that might affect the patient, including side effects, cost, efficacy, and others. Social prescribing requires a similar approach that can range from a clinician simply listening and acknowledging that social isolation and loneliness are real to involvement of a broad interdisciplinary team. The intervention chosen, however, should be tailored to the needs and available resources of each individual.23 A prescription will be most successful if clinicians like Dr J use a systematic approach that can be replicated and used with all patients.

References

- Mund M, Freuding MM, Möbius K, Horn N, Neyer FJ. The stability and change of loneliness across the life span: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2020;24(1):24-52.

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. National Academies Press; 2020.

- Cudjoe TKM, Roth DL, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Thorpe RJ Jr. The epidemiology of social isolation: national health and aging trends study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(1):107-113.

-

Cacioppo JT, Patrick W. Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection. WW Norton; 2009.

- Perissinotto CM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1078-1083.

-

Paul E, Bu F, Fancourt D. Loneliness and risk for cardiovascular disease: mechanisms and future directions. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021;23(6):68.

- Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30(4):377-385.

- Segrin C, Domschke T. Social support, loneliness, recuperative processes, and their direct and indirect effects on health. Health Commun. 2011;26(3):221-232.

-

Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Aging and loneliness: downhill quickly? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16(4):187-191.

- Gronewold J, Engels M, van de Velde S, et al. Effects of life events and social isolation on stroke and coronary heart disease. Stroke. 2021;52(2):735-747.

- Maharani A, Pendleton N, Leroi I. Hearing impairment, loneliness, social isolation, and cognitive function: longitudinal analysis using English longitudinal study on ageing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(12):1348-1356.

- Falvey JR, Cohen AB, O’Leary JR, Leo-Summers L, Murphy TE, Ferrante LE. Association of social isolation with disability burden and 1-year mortality among older adults with critical illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(11):1433-1439.

-

Pardhan S, Islam MS, López-Sánchez GF, Upadhyaya T, Sapkota RP. Self-isolation negatively impacts self-management of diabetes during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2021;13(1):123.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, Sbarra DA. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol. 2017;72(6):517-530.

-

Regional Office for the Western Pacific. A toolkit on how to implement social prescribing. World Health Organization; 2022. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1424690/retrieve

-

Morris SL, Gibson K, Wildman JM, Griffith B, Moffatt S, Pollard TM. Social prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of service providers’ and clients’ experiences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):258.

- Porter J, Boyd C, Skandari MR, Laiteerapong N. Revisiting the time needed to provide adult primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(1):147-155.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20-40.

-

Van Baarsen B, Smit JH, Snijders AB, Knipscheer KPM. Do personal conditions and circumstances surrounding partner loss explain loneliness in newly bereaved older adults? Ageing Soc. 1999;19(4):441-469.

-

Crowe CL, Liu L, Bagnarol N, Fried LP. Loneliness prevention and the role of the public health system. Perspect Public Health. Published online July 11, 2022.

- Kotwal AA, Fuller SM, Myers JJ, et al. A peer intervention reduces loneliness and improves social well-being in low-income older adults: a mixed-methods study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(12):3365-3376.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Perissinotto C. Social isolation and loneliness as medical issues. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(3):193-195.

- Hazeldine E, Gowan G, Wigglesworth R, Pollard J, Asthana S, Husk K. Link worker perspectives of early implementation of social prescribing: a “researcher-in-residence” study. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29(6):1844-1851.

-

Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD000072.

- Wei H, Horns P, Sears SF, Huang K, Smith CM, Wei TL. A systematic meta-review of systematic reviews about interprofessional collaboration: facilitators, barriers, and outcomes. J Interprof Care. 2022;36(5):735-749.

- Sandhu S, Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Financing approaches to social prescribing programs in England and the United States. Milbank Q. 2022;100(2):393-423.

-

Algren MH, Ekholm O, Nielsen L, Ersbøll AK, Bak CK, Andersen PT. Social isolation, loneliness, socioeconomic status, and health-risk behaviour in deprived neighbourhoods in Denmark: a cross-sectional study. SSM Popul Health. 2020;10:100546.

- Cattan M, Kime N, Bagnall AM. The use of telephone befriending in low level support for socially isolated older people—an evaluation. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19(2):198-206.

- Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):238-249.

- Tse MM. Therapeutic effects of an indoor gardening programme for older people living in nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(7-8):949-958.

-

Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, Farley K, Wright K. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e013384.

-

Carnes D, Sohanpal R, Frostick C, et al. The impact of a social prescribing service on patients in primary care: a mixed methods evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):835.

-

Wildman JM, Moffatt S, Steer M, Laing K, Penn L, O’Brien N. Service-users’ perspectives of link worker social prescribing: a qualitative follow-up study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):98.

-

Moffatt S, Steer M, Lawson S, Penn L, O’Brien N. Link worker social prescribing to improve health and well-being for people with long-term conditions: qualitative study of service user perceptions. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e015203.

- Bertotti M, Frostick C, Hutt P, Sohanpal R, Carnes D. A realist evaluation of social prescribing: an exploration into the context and mechanisms underpinning a pathway linking primary care with the voluntary sector. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;19(3):232-245.

-

Pescheny JV, Pappas Y, Randhawa G. Facilitators and barriers of implementing and delivering social prescribing services: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):86.

-

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Opra Widerquist MA, Lowery J. Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): the CFIR Outcomes Addendum. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):7.

-

Hoang P, King JA, Moore S, et al. Interventions associated with reduced loneliness and social isolation in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2236676.

- Eccles AM, Qualter P. Review: alleviating loneliness in young people—a meta-analysis of interventions. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021;26(1):17-33.

- Skivington K, Smith M, Chng NR, Mackenzie M, Wyke S, Mercer SW. Delivering a primary care-based social prescribing initiative: a qualitative study of the benefits and challenges. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(672):e487-e494.

-

Tierney S, Wong G, Roberts N, et al. Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: a realist review. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):49.

- White C, Bell J, Reid M, Dyson J. More than signposting: findings from an evaluation of a social prescribing service. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(6):e5105-e5114.