Abstract

Racism reduces eligibility for health insurance and access to high-quality care for people of color in the United States, and current payment structures exacerbate the resultant de facto racial segregation. Payers and health plans do not adequately support and incentivize clinicians and health care delivery organizations to meet the health needs of minoritized communities. This article describes foundational work needed to create an antiracist culture of equity; the Roadmap to Advance Health Equity; and specific, actionable antiracist payment reform strategies, including increasing access to and the scope of health insurance coverage, antiracism accountability in managed-care contracts, support for the safety-net system, strengthened nonprofit hospital tax status requirements, and payment incentives to advance health equity. Antiracist payment reforms have great potential to desegregate health care systems and to ensure that everyone has a fair opportunity to receive good health services and optimize their health.

Advancing Health Equity With an Antiracist Lens

In his 2005 commencement speech at Kenyon College, writer David Foster Wallace began: “There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, ‘Morning, boys, how’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, ‘What the hell is water?’”1 Those fish couldn’t contemplate the water because it was always around them. When we contemplate how we navigate the waterways of our own day-to-day lives, we realize that we’re just one being in a wider world of interconnected lakes, ponds, and puddles. Yet, as Camara Phyllis Jones opines: “Fish swimming in water may be unaware of the water, but the water in which they swim can be clean or polluted.”2 In the United States, our waterways are the systems and structures that constitute our society, and they’ve been polluted with racism. Their byproduct is a separate and unequal health care system for marginalized populations and one-size-fits-all approaches that fail to meet their needs. Unlike fish who have little choice but to live in a polluted body of water, we have the opportunity to change the environment around us. This article first discusses making the case for a culture of equity and reforming the medical payment system so that it becomes steeped in principles of antiracism to materially ameliorate the imbalances in our segregated health care system. It then discusses specific, actionable antiracist payment reform strategies.

Creating an Antiracist Culture of Equity

Race is a social construct. Our societal norms privilege and reward those who possess or can approximate whiteness.3 Sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant argue that “race has been a master category, a kind of template for patterns of inequality, marginalization, and difference throughout US history.”4 Racism is not limited to easily identified bad actors. It manifests personally, institutionally, and structurally.5 Structural racism has caused inequities in wealth, income, education, housing, incarceration, and employment, leading to and exacerbating health disparities.6 For example, enslaved African Americans lost nearly $20.3 trillion in unpaid wages, a theft that reverberates within the Black community today.7 US President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law in 1862 to disburse ancestral lands.8 By 1934, the Homestead Act and federal Indian policy had gifted more than 270 million acres of Native American land to individuals.8 In order to create change, one must understand how historical acts of racism and colonialism influence the contemporary moment.

Structural racism can affect the health of racially marginalized populations through economic and social drivers of health (SDOH). For example, in many municipalities, redlining systematically denied Black homeowners good mortgage rates in desirable neighborhoods.9,10 Therefore, a disproportionate number of Black people live in food deserts where it is difficult to access affordable fresh fruits and vegetables.11 Lack of access to healthy foods leads to higher rates of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.12

Because the health care payment system was created within a society rife with structural racism, meaningful reforms require being actively antiracist, or “accepting that all actors in a racialized society are affected materially … and ideologically by the racial structure.”13 Reforms must avoid adopting a mantra of color-blindness, which ignores how racism and racial bias disproportionately impact people of color. Antiracist payment reforms in the health insurance industry and public policy, however, have been limited because the nation has not truly valued and prioritized advancing health equity, nor has it intentionally adopted an antiracist lens. Therefore, we offer practical strategies that organizations can implement to create a culture of equity and restructure payment systems to advance health equity that they can tailor to their individual contexts.

Physicians and other health care professionals should advocate within their organizations to create a culture of equity and for antiracist payment reform14,15 (see Figure 1). While specific approaches may vary for each organization, universal starting points apply to all. Organizations should either have specific in-house expertise or consult an outside partner skilled in uncovering how racial bias can be reinforced within poorly designed structures, policies, and rules. Organizations should provide meaningful decision-making power and support to internal diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) staff. In addition, all employees at all levels should receive training in how to implement an antiracist lens in their day-to-day work and policy decisions.16,17,18

Figure 1. Create an Antiracist Culture of Equity

In our DEI work at the University of Chicago, applying relational cultural theory with an antiracist lens22 has helped us cultivate a culture of equity. Developed by Jean Baker-Miller, relational cultural theory prioritizes growth-fostering relationships. It emphasizes discussions and relationship building, uncovering bias and power imbalances, and encouraging compassion as well as racial and social justice.21,23 Application of relational cultural theory would include each employee having the opportunity to provide feedback informed by their job function and experiences with patients and communities. Lessening the impact of norms and processes that reflect a culture of white supremacy—such as defensiveness, discomfort with conflict, power hoarding, and paternalism—is essential to ensure that organizations adequately address the needs and concerns of racially minoritized populations.24 These norms can make payment reform difficult, if not impossible.

Implementing Antiracist Payment Reform

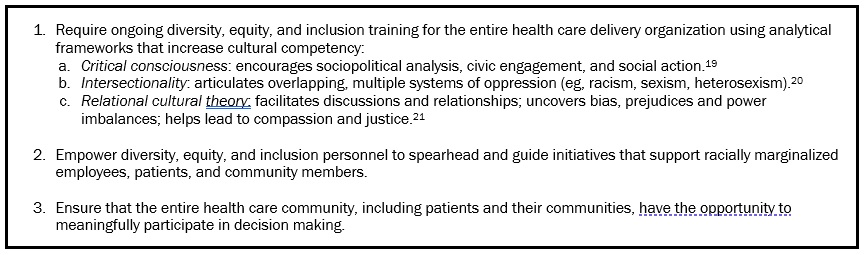

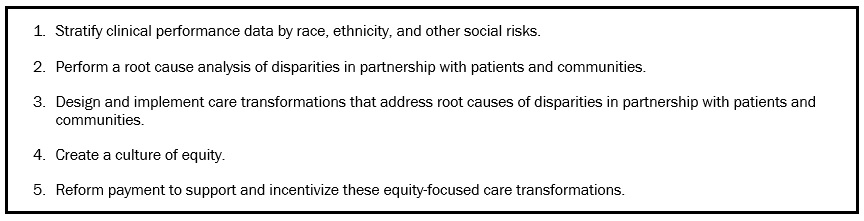

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Roadmap to Advance Health Equity outlines a process by which payment intentionally supports and incentivizes care transformations that address medical and social issues driving health and health care inequities (see Figure 2).14,15,25

Figure 2. How to Implement the Roadmap to Advance Health Equity

With regard to Figure 2, Steps 2 through 4, payers, health plans, and health care delivery organizations must engage patients and communities in identifying health disparities and, instead of simply soliciting feedback, create avenues for those communities to enact meaningful, lasting change. Evidence-based interventions known to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in care and outcomes include culturally tailored approaches, comprehensive team-based care, and partnering with community health workers.15,25 Care delivery systems that extend service hours beyond the standard workday to accommodate those without the flexibility to take time off from work might also reduce inequities.

With regard to Figure 2, Step 5, an antiracist approach to payment reform is, by definition, proactive, seeking out and naming racist practices and implementing antiracist solutions (see Supplementary Appendix). Below, we describe 6 ways to implement antiracist payment reform.

Increase access to quality health insurance. Racism reduces access to care and the quality of care that people of color receive. For example, racially marginalized groups are overrepresented in the Medicaid system, where they often have difficulty accessing care because Medicaid reimbursement rates are frequently below those of commercial insurers.26,27 In fact, the Medicaid program was enacted in 1965 on a foundation of structural racism. As part of negotiations over the creation of the Medicare and Medicaid programs, President Lyndon B. Johnson cut a deal with Southern congressmen by which Medicaid would be a joint federal-state program, enabling states hostile to civil rights to retain significant control over program benefits and funding as well as the health of the disproportionate numbers of Black beneficiaries.28,29 Jamila Michener writes: “Medicaid is racialized, despite being facially colorblind, because race has been a central factor in shaping policies, discourse, design, implementation, and perceptions of it.”30 Thus, an antiracist—not a color-blind—approach to payment reform is imperative for meaningful change.

Barriers to care also persist for people of color in the Medicare system, partly because of the maldistribution of health care resources. An analysis of a 2001-2002 survey found that about 20% of primary care physicians accounted for 80% of visits by Black people nationwide.31 Those physicians were more likely to report being unable to provide high-quality care, elective admission to hospitals, and access to high-quality subspecialists and diagnostic imaging.31 An antiracist approach to payment reform would improve the distribution of and access to primary and specialty care by providing incentives to care for underserved populations and to cover telehealth.

Improve the scope of insurance coverage for medical and social needs. Many insurance plans provide limited or no coverage for interventions to address patients’ social needs and SDOH.32 Interventions for marginalized populations are frequently held to the higher bar of cost savings rather than value. For example, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 required budget neutrality or cost savings for models of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to be continued even if there were big payoffs in health with slightly more money included.33 These criteria limit what innovation is possible, even as the CMMI constructively identifies advancing health equity as a priority.34,35

Make antiracism nonnegotiable in managed-care contracts. State Medicaid agencies should require managed-care health plans to implement antiracism measures with accountability as nonnegotiables in contract agreements.36,37,38,39 The medical director of Minnesota Medicaid and MinnesotaCare, Nathan Chomilo, argues: “Addressing structural racism, promoting anti-racism, and capturing and measuring health equity are part of the expectations for any managed care plan who’s serving our enrollees.”40 One way for organizations to demonstrate similar expectations would be to require potential vendors to answer questions such as: How does your organization explicitly implement antiracist measures? What correctives have your organization implemented to become antiracist, and what is your plan for maintaining and improving upon those correctives?

Another potential reform that state Medicaid agencies could enact would be to require racial equity impact assessments of plans’ policies and actions, including measures of racial discrimination. Jamila Michener developed a Racial Equity Framework for Assessing Health Policy, which includes examining disproportionality in the benefits and burdens of policies across racial and ethnic groups and the extent to which communities of color influence policy.41 Another practical tool is the City of St Paul Department of Safety and Inspection’s Racial Equity Assessment Worksheet, which helps organizations plan and analyze policies and programs in 5 steps: (1) setting outcomes, (2) involving stakeholders and analyzing data, (3) examining benefits and burdens, (4) developing short- and long-term strategies to eliminate inequities, and (5) raising racial awareness and being accountable.42 These tools can all serve as blueprints for holding vendors and states accountable.

Strengthen support for the safety-net system. It is critical to support, rather than penalize, provider organizations caring for racially marginalized populations.25,43 For example, initially Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which tries to link payment to quality of care, disproportionately hurt the finances of safety-net hospitals caring for patients with high social risk and increased readmission rates for Black patients.44 Safety-net hospitals that care for a higher percentage of racially marginalized populations could do worse in pay-for-performance programs than non-safety-net hospitals, leading to decreased resources, which could in turn lead to worsened care and lower revenue in future pay-for-performance cycles. Some safety-net providers do not have adequate infrastructure for data, quality improvement, and analytics to compete in value-based payment programs. Frequently, there is insufficient risk adjustment for patient social risk factors that affect clinical performance metrics, making the playing field for safety-net providers uneven and exacerbating a preexisting, racist payment structure.45,46 Social risk adjustment for payment could make alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations, more likely to enroll and care for marginalized communities.47,48

Define and operationalize nonprofit hospital tax status to substantially benefit marginalized communities. The criteria for what qualifies as community benefit is broad and lax and varies by locality, but it can be operationalized with an antiracist lens.49 Nonprofit hospitals differ greatly in the amount of community benefit and charity care they provide,50 with some hospitals not meeting the charitable intent of the tax code.51 An antiracist lens would pay specific attention to how existing payment structures contribute to inadequate resources among safety-net providers and negatively affect marginalized populations.

Implement payment incentives to advance health equity. Payment incentives to produce equitable outcomes could help drive change.36,48,52 Fee-for-service payment, which incentivizes volume of services, not value or equity, is still prevalent. However, value-based payment programs and alternative payment models could reward disparities reduction and improvement in the care and outcomes of racially minoritized populations if they were intentionally designed to advance health equity.52 At the federal level, the CMMI is initiating innovations designed to improve care and outcomes of marginalized populations. For example, the ACO REACH (realizing equity, access, and community health) program will test accountable care organization (ACO) models that incorporate innovative payment approaches to improve care delivery in underserved communities and measurably reduce health disparities.53 Moreover, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network Health Equity Advisory Team published a technical guide providing recommendations on how care delivery redesign, payment incentives and structure, and performance measurement can advance health equity.48 CMS could enact financial withholds if health care organizations do not reduce gaps in care and outcomes. Plans and health care organizations could track and reward patient-centered measures that patients and communities find meaningful. Any incentive plan, however, should have measures to prevent gaming and include monitoring to identify and address negative, unintended consequences.

At the state level, the Oregon Medicaid program supports and incentivizes coordinated care organizations to address patients’ social needs through an SDOH screening incentive metric, flexible funding for health-related services, required investment in SDOH and equity, increased community involvement in SDOH investment, and risk-adjusted global budgets with bonuses if performance metrics are met.54 The Massachusetts Medicaid ACO program requires assessment of health-related social needs of the enrolled population, available community resources, and gaps in community services. It also provides incentives to address SDOH via encouraging organizations to partner with community-based organizations, offering flexible services, and adjusting payment for the social risk of beneficiaries.55 Implementing antiracist policies requires ongoing review and understanding of structural and racist drivers of health care and outcomes.20,22,23,56

Broader changes to the health care system that could further integrate currently segregated systems of care include universal health insurance, lowering the age of eligibility for Medicare, adequately funding Medicaid, and implementing all-payer total cost of care systems, such as in Maryland, which provide strong incentives for preventive and primary care for the populations served to reduce costly hospital admissions.57

Conclusion

Being antiracist is more than not being racist. It requires ongoing commitment to advocating for and enacting racial equity. Identifying racism and integrating antiracism into an organization is every person’s responsibility. It can be difficult to think about how to enact change, particularly within Byzantine institutional structures that make us feel like small guppies in a giant ocean. As theorist Audre Lorde once stated: “We operate in the teeth of a system for which racism and sexism are primary, established, and necessary props of profit.”58 Without reform, the medical payment system is in danger of permanently calcifying existing divisions in health care that unfairly disadvantage people of color with low incomes. Quality medical care should not be tied to one’s race or paycheck.

Just because change is difficult, it doesn’t mean we should opt for things to stay the same. All members of the medical community—from payers, to providers, to support staff—have a responsibility to reform our separate and unequal system. The question is not if but how racism manifests in the system. For a payment structure to do the most good for the most people, it must be reviewed regularly to stop problems, prevent them from beginning, and develop antiracist reforms that advance health equity. Antiracist payment reforms have great potential to desegregate health care systems and to ensure that everyone has a fair opportunity for optimal health.

References

-

This is water by David Foster Wallace (full transcript and audio). Farnam Street Media blog. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://fs.blog/david-foster-wallace-this-is-water/

- Jones CP. Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon. 2002;50(1-2):7-22.

-

Singletary KA. Everyday matters: haunting and the Black diasporic experience. In: Florvil T, Plumly V, eds. Rethinking Black German Studies: Approaches, Interventions, and Histories. Peter Lang; 2018:137-168.

-

Omi M, Winant H. Racial Formation in the United States. 3rd ed. Routledge; 2014.

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212-1215.

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463.

-

Saraiva C. Bloomberg Pay Check podcast. Four numbers that show the cost of slavery on Black wealth today. March 18, 2021. Accessed January 15, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-18/pay-check-podcast-episode-2-how-much-did-slavery-in-u-s-cost-black-wealth

-

The Homestead Act of 1862. National Archives. June 2, 2021. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/homestead-act#background

-

Illing S. The sordid history of housing discrimination in America. Vox. Updated May 5, 2020. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/12/4/20953282/racism-housing-discrimination-keeanga-yamahtta-taylor

-

Rothstein R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing; 2018.

-

Bower KM, Thorpe RJ Jr, Rohde C, Gaskin DJ. The intersection of neighborhood racial segregation, poverty, and urbanicity and its impact on food store availability in the United States. Prev Med. 2014;58:33-39.

-

Healthy food environments: improving access to healthier food. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 10, 2020. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/healthy-food-environments/improving-access-to-healthier-food.html

-

Bonilla-Silva E. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 4th ed. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2014.

-

Chin MH. Advancing health equity in patient safety: a reckoning, challenge and opportunity. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30:356-361.

- Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992-1000.

- Peek ME, Vela MB, Chin MH. Practical lessons for teaching about race and racism: successfully leading free, frank, and fearless discussions. Acad Med. 2020;95(12)(suppl):S139-S144.

- Chen CL, Gold GJ, Cannesson M, Lucero JM. Calling out aversive racism in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(27):2499-2501.

- Vela MB, Erondu AI, Smith NA, Peek ME, Woodruff JN, Chin MH. Eliminating explicit and implicit biases in health care: evidence and research needs. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43(1):477-501.

-

Paradis E, Nimmon L, Wondimagegn D, Whitehead CR. Critical theory: broadening our thinking to explore the structural factors at play in health professions education. Acad Med. 2020;95:842-845.

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 1989;1(8):139-167.

- Jordan JV. Relational-cultural theory: the power of connection to transform our lives. J Humanist Couns. 2017;56(3):228-243.

-

Todić J, Cook SC, Spitzer-Shohat S, et al. Critical theory, culture change, and achieving health equity in healthcare settings. Acad Med. 2022;97:977-988.

-

Cook SC, Todić J, Spitzer-Shohat S, et al. Opportunities for psychologists to advance health equity: using liberation psychology to identify key lessons from sixteen years of praxis. Am Psychol. Forthcoming 2023.

-

Jones K, Okun T. Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups. ChangeWork; 2001.

- Chin MH. New horizons—addressing healthcare disparities in endocrine disease: bias, science, and patient care. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(12):e4887-e4902.

-

Structural racism and chronic underfunding of Medicaid. America’s Essential Hospitals. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://essentialhospitals.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/MedicaidEquity-WhitePaper-Part1.pdf

- Zuckerman S, Skopec L, Aarons J. Medicaid physician fees remained substantially below fees paid by Medicare in 2019. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):343-348.

-

Michener J. Michael Brooks Show. Illicit history-2-Medicaid vs states’ rights. June 26, 2019. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZRtakJsEc74

-

Nolen LT, Beckman AL, Sandoe BE. How foundational moments in Medicaid’s history reinforced rather than eliminated racial health disparities. Health Affairs Forefront. September 1, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200828.661111/

- Michener JD. Politics, pandemic, and racial justice through the lens of Medicaid. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(4):643-646.

- Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):575-584.

- Gunter KE, Peek ME, Tanumihardjo JP, et al. Population health innovations and payment to address social needs among patients and communities with diabetes. Milbank Q. 2021;99(4):928-973.

-

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, 42 USC §1315a (2022).

-

Brooks-LaSure C, Fowler E, Seshamani M, Tsai D. Innovation at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: a vision for the next 10 years. Health Affairs Forefront. August 12, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210812.211558/full/

-

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Innovation Center strategy refresh. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://innovation.cms.gov/strategic-direction-whitepaper

-

McGinnis T, Smithey A, Patel S. Harnessing payment to advance health equity: how Medicaid agencies can incorporate LAN guidance into payment strategies. Center for Health Care Strategies. February 16, 2022. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.chcs.org/harnessing-payment-to-advance-health-equity-how-medicaid-agencies-can-incorporate-lan-guidance-into-payment-strategies/

-

Application for Renewal and Amendment: Oregon Health Plan 1115 Demonstration Waiver. Oregon Health Plan Authority. December 1, 2021. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HSD/Medicaid-Policy/Documents/Waiver-Renewal-Application.pdf

-

Manatt Health. Centering health equity in Medicaid Section 1115 demonstrations: a roadmap for states. State Health & Value Strategies; February 2022. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Demonstrations-Health-Equity-Strategies-final.pdf

-

Manatt Health. Centering health equity in Medicaid: Section 1115 demonstration strategies. State Health & Value Strategies. February 2022. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Companion-Document-Demonstrations-Health-Equity-Strategies-final.pdf

-

Moran L. Fostering health equity: perspectives from a Medicaid medical director. Center for Health Care Strategies. May 20, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.chcs.org/fostering-health-equity-in-medicaid-medicaid-medical-director-perspectives/

-

Michener J. A racial equity framework for assessing health policy. Commonwealth Fund. January 20, 2022. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2022/jan/racial-equity-framework-assessing-health-policy

-

Racial Equity Assessment Toolkit. Department of Safety and Inspections, St Paul, Minnesota. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.stpaul.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/Licensing%20-%20Initial%20Applications%20-%20%20Racial%20Equity%20Assessment%20%2012-18-17.pdf

- Chin MH. Creating the business case for achieving health equity. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):792-796.

-

Chaiyachati KH, Qi M, Werner RM. Changes to racial disparities in readmission rates after Medicare’s hospital readmissions reduction program within safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184154.

-

Risk adjustment for socioeconomic status or other sociodemographic factors. National Quality Forum. August 15, 2014. Accessed December 31, 2020. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2014/08/Risk_Adjustment_for_Socioeconomic_Status_or_Other_Sociodemographic_Factors.aspx

-

A roadmap for promoting health equity and eliminating disparities: the four I’s for health equity. National Quality Forum. September 14, 2017. Accessed December 31, 2020. https://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/c-d/Disparities/Disparities_Guide.aspx

- Yasaitis LC, Pajerowski W, Polsky D, Werner RM. Physicians’ participation in ACOs is lower in places with vulnerable populations than in more affluent communities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1382-1390.

-

Health Equity Advisory Team, Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. Advancing health equity through APMs: guidance for equity-centered design and implementation. MITRE Corporation; 2021. Accessed February 1, 2022. http://hcp-lan.org/workproducts/APM-Guidance/Advancing-Health-Equity-Through-APMs.pdf

-

Zare H, Eisenberg M, Anderson G. Charity care and community benefit in non-profit hospitals: definition and requirements. Inquiry. 2021;58:469580211028180.

- Zare H, Eisenberg MD, Anderson G. Comparing the value of community benefit and tax-exemption in non-profit hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(2):270-284.

- Bai G, Zare H, Eisenberg MD, Polsky D, Anderson GF. Analysis suggests government and nonprofit hospitals’ charity care is not aligned with their favorable tax treatment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(4):629-636.

-

Patel S, Smithey A, Tuck K, McGinnis T. Leveraging value-based payment approaches to promote health equity: key strategies for health care payers. Center for Health Care Strategies; January 2021. Accessed February 27, 2021. https://www.chcs.org/media/Leveraging-Value-Based-Payment-Approaches-to-Promote-Health-Equity-Key-Strategies-for-Health-Care-Payers_Final.pdf

-

ACO Reach. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Updated August 25, 2022. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/aco-reach

-

Oregon leverages Medicaid to address social determinants of health and health equity. Center for Health Systems Effectiveness. June 2021. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.ohsu.edu/sites/default/files/2021-06/Oregon%20Medicaid%20addresses%20SDOH%20and%20health%20equity1.pdf

-

Kaye N. Massachusetts fosters partnerships between Medicaid accountable care and community organizations to improve health outcomes. National Academy for State Health Policy. March 12, 2021. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.nashp.org/massachusetts-fosters-partnerships-between-medicaid-accountable-care-and-community-organizations-to-improve-health-outcomes/

- Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):782-787.

- Sapra KJ, Wunderlich K, Haft H. Maryland total cost of care model: transforming health and health care. JAMA. 2019;321(10):939-940.

-

(1981) Audre Lorde, “The uses of anger: women responding to racism.” Blackpast. August 12, 2012. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/speeches-african-american-history/1981-audre-lorde-uses-anger-women-responding-racism/#:~:text=We%20are%20not%20here%20as,and%20necessary%20props%20of%20profit