Abstract

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program has dramatically improved the lives of undocumented youth in the United States. In particular, DACA has improved these young adults’ health by improving the social determinants of health. Furthermore, as health professionals, DACA recipients increase the diversity of medicine and the health professions and are thereby suited and well positioned to promote health equity. The medical profession should continue its support for ad hoc legislative remedies, such as the DREAM Act, which target relief for particular populations of undocumented youth. In addition, the medical profession should highlight the need for a legislative solution that goes beyond a one-time fix and corrects the systemic marginalization of undocumented youth.

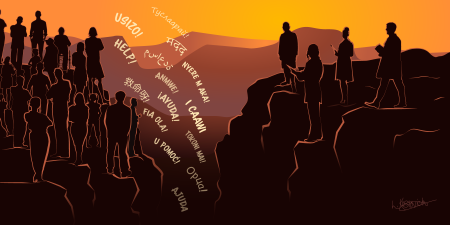

How DACA Reframed Undocumented Immigrants’ Roles in US Society

The United States has a large number of persons who lack a lawful immigration status and who have become integrated into the fabric of society. Estimates place the number of undocumented immigrants at between 9 and 12 million persons, approximately two-thirds of whom are believed to have resided in the United States for more than 10 years.1 These undocumented immigrants include approximately 700 000 young adults who have had a temporary reprieve through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.1 DACA recipients receive a 2-year, renewable stay of action on their immigration status. They also receive an Employment Authorization Document (EAD) that enables them to secure lawful employment. One qualitative study concluded that the program is “arguably the most successful policy of immigrant integration in the last three decades” because of the many improvements it facilitated in the socioeconomic situation of its recipients.2

The creation of the DACA program by a presidential memorandum was announced on June 15, 2012.3 To be eligible, a person must have been brought to the United States prior to the age of 16, have lived continuously in the United States for at least 5 years, have no significant criminal record, and have achieved a high school diploma or the equivalent.4 The program was instituted by President Obama following the repeated failure of legislative efforts, such as the Development, Relief and Education of Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, which would have provided a pathway to citizenship for this population.5 As a result, DACA has always had a tenuous, quasi-legal status, subject to the will of the President of the United States and the administrative rules governing his or her exercise of prosecutorial discretion. The Trump administration rescinded the program on September 5, 2017.6 However, this recission was recently vacated by the Supreme Court of the United States on administrative procedure grounds.7 This court decision has kept the program alive temporarily but its future remains tenuous.8

DACA is based on several considerations of fairness and justice. Because DACA recipients were brought to the United States as children, their exclusion from the benefits of citizenship cannot be justified as punishment for any legal transgression they committed. Furthermore, because these young people grew up in the United States, their identity is bound up with this country. Deportation is the equivalent of exile to a foreign country. DACA created conditions for these recipients to live their lives more fully, including improving their chances for a healthy life. Indeed, since the inception of DACA in 2012, it has become clear that this temporary relief measure promotes health equity for a defined group of undocumented youth by significantly improving the social determinants of health. DACA also potentially promotes health equity for underserved communities by increasing the diversity of the health care workforce. For these reasons, medical professional and educational organizations, such as the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), have explicitly supported DACA and the creation of a pathway to citizenship for these young people.9

Current legislative proposals to remedy the situation of undocumented youth would create a pathway to citizenship for a particular group of those currently affected. Such legislation would provide a one-time fix. The problem would recur for future undocumented youth who meet the same or similar criteria but who would have no path to citizenship readily available. Thus, even with the legislative creation of a path to citizenship, a systemic barrier to health equity would persist.

The medical profession has developed an awareness of systemic and structural causes of health inequities and advocated to alleviate them. The recent calls by the American Medical Association (AMA)10 and the AAMC11 and other medical professional societies12 to address structural racism in policing and in society evidence an awareness that systemic injustices systematically produce inequities. This awareness should also guide advocacy for undocumented youth.

Health inequity is, by definition, a health disparity that is created by social structures that systematically disadvantage certain groups.13 Correcting systemic injustice requires changing the structures that produce the inequities for all those who are marginalized and treated unfairly, not merely an arbitrarily selected group. Medicine must play a prophetic role and draw attention to the need for an ongoing structural solution to the plight of undocumented youth. This role implies advocating for a pathway to citizenship for all undocumented youth, present and future, who meet certain criteria. In essence, it is to move beyond advocacy for versions of the DREAM Act as currently envisioned to advocate for a Perpetual DREAM Act.

How DACA Fosters Health Equity

Harvard sociologist Roberto Gonzales has termed being undocumented a “master status.”14 A master status is a category that impacts every aspect of one’s life. Being undocumented limits opportunities for education, employment, housing, and health insurance. While many find ways to circumvent some of the barriers this immigration status poses, those barriers will prevent others from making their full personal and economic contribution to society and must be addressed.

Young people who are undocumented in the United States often grow up unaware of their immigration status. They have the right to attend public school,15 and they often experience childhood and early adolescence much as their citizen peers. Late adolescence is typically the period of discovery of their problematic immigration status.16 Undocumented youth have often learned about their status when seeking to gain a driver’s license,17 because, in most states, people who are undocumented are ineligible for a driver’s license.18 As a result, their families might disclose their status to them so that they understand this limitation. As undocumented youth enter adulthood, the limitations of their status dominate their future prospects. Most importantly, undocumented immigrants lack the ability to work lawfully. As a result, most forms of gainful employment will be unattainable. Furthermore, anti-immigrant legislation passed in the 1990s declares undocumented immigrants ineligible for any federal benefits,19 including federal student loans, Medicaid, and even buying marketplace health insurance plans under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).20

DACA generates health equity for DACA recipients. DACA enhanced the well-being of eligible undocumented youth by improving social determinants of health. A review of the available data21 and a qualitative study2 have shown the dramatic effects of this program on employment, income, and education. Because DACA recipients receive a work permit, the program led to increased wages and expanded the kinds of employment available to them. In particular, DACA recipients have been able to secure employment that is better suited to their particular educational and skill levels.2 And, of course, gaining skilled employment brings increased income.

DACA has also had a significant impact on the educational attainment of recipients. DACA requires that recipients be attending high school or have earned a high school diploma or the equivalent.4 But it has no provisions for higher education. Nevertheless, DACA has increased access to higher education. DACA recipients are enrolling in college at a rate similar to that of their citizen peers.21 This is surprising, given their lack of access to federal aid, such as student loans. However, DACA enables students to complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid,22 which is used by most universities and lenders to evaluate student need. As a result, many institutions of higher education have increasingly deemed these applicants eligible for various scholarships23 and other institutional aid and some private student loans are offered.24 Presumably, DACA drew attention to the plight of these students and led colleges and universities to provide more equitable access to higher education and financial aid. It has led medical schools to make a significant investment in enabling some DACA recipients to matriculate and to go on to residencies.9 Nevertheless, the pathway through higher education does not convey the full array of opportunities. For instance, DACA recipients often need to work to obtain money for tuition and are therefore more likely to initially enroll in a 2-year college than their citizen peers.21 All this is somewhat indirect but rather significant evidence that DACA fosters health equity among DACA recipients. If improving education and income levels generally leads to improvements in health, then DACA improves health.

However, there is also more direct evidence of DACA’s effects on health. A retrospective, quasi-experimental study utilizing data from the US National Health Interview Survey concluded: “Economic opportunities and protection from deportation for undocumented immigrants, as offered by DACA, could confer large mental health benefits to such individuals.”25 Another study has shown that children of mothers who are DACA-eligible have 50% fewer diagnoses of adjustment and anxiety disorder than the children of ineligible mothers.26 The obvious hypothesis is that because of DACA, the emotional well-being of mothers is improved by reduced fear of deportation and the advantages of a work permit. The mother’s well-being is likely an important factor in the child’s well-being. This study highlights the fact that health equity has a strong communal aspect. The well-being of any individual affects the well-being of those intimately engaged with that person. To provide health equity to one person is to provide it to others. This is the key insight behind opening medicine and the health professions to DACA recipients.

DACA recipients produce health equity for others. When the Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine became the first medical school in the United States to declare DACA recipients eligible to apply and compete for seats in future classes, I and my colleagues made clear that this action was motivated in part by the contribution that DACA recipients could make to the physician workforce.27,28,29 DACA recipients can increase the diversity of medical school classes and eventually the physician workforce. And their skills and perspective may be particularly helpful to some communities. DACA recipients are typically bilingual and bicultural. Having grown up and been educated in the United States, they understand American society and have also assimilated the worldview of their immigrant parents. DACA recipients represent many countries of birth and reflect US immigration patterns.30

DACA recipients bring the commonly asserted benefits of diversity to medicine and medical education.31 Physicians from underserved communities are more likely to choose to serve such communities during their careers.32 Patients who are treated by a physician who is racially or ethnically concordant with them tend to select preventive measures and better adhere to treatment plans, which leads to improved outcomes, including lower mortality.33,34 It seems that such physicians have the skills to gain the trust of their patients. Although such skills would always seem to be important, they are even more crucial during public health emergencies, such as a pandemic, when all communities need to comprehend and adhere to evolving guidance from health officials. And, of course, trust will be important in such communities when a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is deployed in the future.35

Children of mothers who are DACA-eligible have 50% fewer diagnoses of adjustment and anxiety disorder than the children of ineligible mothers.

Educators often assert that a key benefit of a diverse student body is that it likely contributes to widespread cultural sensitivity and awareness.32 Training side-by-side with their citizen peers enables DACA recipients to learn about and from them. As a result, other medical students learn more about the cultures and needs of immigrant patients.36 This reciprocal learning leavens the broader physician workforce.31

Of course, DACA physicians are just the tip of the iceberg in health care. Many, many more DACA recipients work in related positions in health care. More than 60 000 DACA-eligible persons work in health care positions, including 30 000 who are frontline health care workers such as registered nurses, home health aides, and nurses’ aides.37 Furthermore, many DACA recipients are essential health care workers, such as clinic receptionists.38 The same cultural and linguistic skills that likely make DACA physicians effective with underserved populations also make these health care workers particularly qualified to treat underserved immigrant populations.

In sum, DACA has unleashed the potential of approximately 700 000 young adults and enabled them to more fully integrate into the fabric of the society in which they have been raised and educated. This integration has improved their standing in terms of many of the major social determinants of health. Moreover, DACA has facilitated the much-needed integration of a diverse population into the health care workforce, which promotes both health in the general population and health equity for underserved populations. But DACA has never been the perfect answer to the situation of undocumented youth and was initially conceived as a bridge to a path to citizenship that should come from legislation.3

Need for a Pathway to Citizenship

The creation of a pathway to citizenship is important for a number of reasons. First, while many DACA recipients have overcome some of the barriers to achievement, their long-term health and well-being is to some extent dependent on gaining full participation in the social systems of the United States. For instance, access to key facilitators of opportunity (eg, federal student loans, marketplace health insurance through the ACA, and safety net programs such as Medicaid) enable citizens to secure a modicum of health and quality of life. Although DACA unleashed the economic potential of recipients and improved indices of the social determinants of health, a pathway to citizenship is needed so that they can realize their full potential to attain a quality life that maximizes their contribution to society. Second, basic fairness requires this pathway to citizenship. DACA recipients contribute to society in the same ways that people who are raised in the United States contribute. They bear the imprint of American culture and ideals. And because they were children when they entered the country or overstayed a visa, their immigration status is not the result of their having broken a law. Unless we believe that citizenship is granted arbitrarily and is not subject to any standards of justice, there is no moral basis for denial of a pathway to citizenship.

Medical education and medicine have a record of support for DACA. Key organizations, such as the AMA, have publicly advocated against the rescinding of DACA and expressed support for a pathway to citizenship.39 This stance is appropriate given the health equity considerations involved. A pathway to citizenship as presently conceived in various versions of the DREAM Act would help several million young people. However, it is important to note that the current proposals are one-time fixes aimed at specific, identifiable persons. They vary in scope, but none make a systemic change that would provide a pathway in the future to similarly situated undocumented youth. In essence, these proposals are akin to supporting civil rights legislation that covered a particular group of African Americans and accepted that future generations would live under Jim Crow laws. Helping some people is better than helping none. However, the inadequacy of a one-time fix for particular people must always be recognized.

The best-known legislative proposal to provide a pathway to citizenship for undocumented youth is called the DREAM Act. The DREAM Act was first introduced in 2001 and has come close to passage on a number of occasions. The criteria that define eligibility for DACA were derived from earlier iterations of this proposed legislation. The most recent version, the American Dream and Promise Act (ADPA), was passed by the House of Representatives in 2019 but has not been passed by the US Senate.40

Approximately 800 000 people were protected by DACA at the time that it was closed to new applicants by the Trump administration’s recission on September 5, 2017.41 An additional million young people would have become DACA-eligible when they reached their sixteenth birthday.41 Thus, if one granted a pathway to citizenship to all DACA-eligible individuals, approximately 1.8 million individuals would be eligible to become citizens. By contrast, the ADPA covers 3.5 million people.41 This difference in coverage is based on technicalities in the eligibility requirements (eg, DACA required that individuals arrive prior to the age of 16 while the ADPA cut-off is age 18). Furthermore, DACA eligibility is dependent on individuals having already been present in the United States on June 15, 2012, while the ADPA requires individuals to have been present in the United States for at least 4 years prior to the date when it is enacted.42 From the standpoint of both health equity and justice, being more inclusive is better than less inclusive.

Including as many undocumented young persons as possible in any legislation to provide a pathway to citizenship would extend the opportunity to achieve the conditions for a healthy life to a greater number of individuals. And such legislation would add to the number of people who possess the qualities, such as bilingualism and biculturalism, that are an asset to the health care infrastructure. Moreover, a more inclusive legislative proposal would highlight the shortcomings of current legislative proposals. The day a current version of the DREAM Act passes, the problem begins to recur. That is, there will be some fluctuating number of people who arrived in the United States as minors, became acculturated to US society, and are unable to attain a lawful immigration status. The same considerations of justice and equity that command support for DACA and the DREAM Act require that we create a systemic solution that prevents the marginalization and exclusion of undocumented youth in the future.

The ability of undocumented youth to thrive as healthy human beings will be compromised by their lack of a lawful immigration status. Physicians in their offices and clinics again will seek to support them in their struggles while new legislation is advanced. Their situation will also call for justice. A more systemic approach is needed and should increasingly become the focus of advocacy.

The pathway to citizenship that the DREAM Act seeks to make available to the current population of undocumented youth must also be made available to undocumented youth in perpetuity. The arguments for parity are the same as those for adjusting the status of the current group of DACA recipients. Namely, DACA recipients are Americans culturally and in terms of their identity, ie, the United States is their country. And, as child immigrants, they simply did not violate our immigration statutes. To deport them is to levy a cruel punishment with significant health implications on people who have done no wrong.

Conclusion

I have argued that it is within the mission of the medical profession and medical education to advocate for a structural solution to the plight of undocumented youth. We must not be unrealistic by assuming that medicine alone has the ability to bring about this change. After all, the national debate regarding a pathway to citizenship for undocumented youth has been stalled since the failure to pass the DREAM Act in 2001. Nevertheless, medicine can help to frame future debates about undocumented youth by being true to its mission of advocating for structural changes in society that foster health equity and alleviate problems that confront physicians. This is simply how medicine typically proceeds in our current era.

I noted earlier how odd it would be for medicine to advocate for the civil rights of a particular group of African Americans but to remain silent on structural reforms to alleviate the same impediments to the civil rights of all African Americans. Medicine now calls for an end to systemic racism in policing, not simply for justice for particular victims. This position follows from considerations of consistency, public health, and justice.

Advocacy for systemic change for undocumented youth is also rooted in the experience of physicians. Without an ongoing, regularized pathway to citizenship for undocumented youth, physicians and health professionals will always find themselves in the role of having to advocate for this group and seeking ad hoc ways to help their undocumented patients achieve health equity. The roots of medical professionals’ advocacy in their concern for patients adds to the credibility of their message for systemic change. Physicians and their professional organizations have little stake in ideological battles over open borders or particular views of immigration. But they have an interest in the patient populations they serve. As a result, the voice of medicine can contribute to the public dialogue in a nonpartisan manner that flows from its mission.

References

-

Kamarck E, Stenglein C. How many undocumented immigrants are in the United States and who are they? Brookings Policy 2020. November 12, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/how-many-undocumented-immigrants-are-in-the-united-states-and-who-are-they/

-

Gonzales RG, Camacho S, Brant K, Aguilar C. The long-term impact of DACA: forging futures despite DACA’s uncertainty. Findings from the National UnDACAmented Research Project (NURP). Immigration Initiative at Harvard; 2019. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://immigrationinitiative.harvard.edu/files/hii/files/final_daca_report.pdf

-

Remarks by the president on immigration. News release. Office of the Press Secretary, The White House; June 15, 2012. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/06/15/remarks-president-immigration

-

Consideration of deferred action for childhood arrivals (DACA). US Citizenship and Immigration Services. Reviewed February 14, 2018. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/consideration-deferred-action-childhood-arrivals-daca

-

American Immigration Council. The DREAM Act, DACA, and other policies designed to protect Dreamers. August 27, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/dream-act-daca-and-other-policies-designed-protect-dreamers

-

Duke EC. Rescission of the June 15, 2012 memorandum entitled “Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion With Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as Children.” September 5, 2017. Accessed October 26, 2020. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2017/09/05/memorandum-rescission-daca

- Dept of Homeland Security v Regents of the Univ of Cal, 591 US ____ (2020). Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-587_5ifl.pdf.

-

Wolf CF. Reconsideration of the June 15, 2012 memorandum entitled “Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion With Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as Children.” US Department of Homeland Security. July 28, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/20_0728_s1_daca-reconsideration-memo.pdf

-

Brief for Association of American Medical Colleges, et al as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Dept of Homeland Association v Regents of the Univ of Cal, 591 US ____ (2020) (Nos. 18-587, 18-588, and 18-589). Accessed September 8, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-10/ocomm-ogr-DACA%20Amicus%20Brief-10082019.pdf

-

AMA Board of Trustees pledges action against racism, police brutality. American Medical Association. June 7, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/ama-statements/ama-board-trustees-pledges-action-against-racism-police-brutality

-

AAMC statement on police brutality and racism in America and their impact on health. News release. Association of American Medical Colleges. June 1, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/aamc-statement-police-brutality-and-racism-america-and-their-impact-health

-

American Academy of Family Physicians. Institutional racism in the health care system. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/institutional-racism.html

- Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27(1):167-194.

-

Gonzales RG. Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America. University of California Press; 2016.

-

Plyler v Doe, 457 US 202 (1982).

- Gonzales RG. Undocumented youth and shifting contexts in the transition to adulthood. Am Sociol Rev. 2011;76(4):602-619.

-

Vargas JA. Dear America: Notes of An Undocumented Citizen. HarperCollins; 2018.

-

National Conference of State Legislatures. States offering driver’s licenses to immigrants. Updated February 6, 2020. Accessed August 10, 2020. https://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/states-offering-driver-s-licenses-to-immigrants.aspx

-

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, Pub L No. 104-193, 110 Stat 2105 (1996).

-

Lopez V, Mackey TK. The health of Dreamers. Health Affairs Blog. February 13, 2018. Accessed October 26, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180209.367466/full/

-

Capps R, Fix M, Zong J. Issue brief: the education and work profiles of the DACA population. Migration Policy Institute. August 2017. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/DACA-Occupational-2017-FINAL.pdf

-

United We Dream. I Have DACA and I can use the FAFSA? Say what?! A reference guide for DACA recipients. May 2014. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://unitedwedream.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/DACAStepsforFAFSA2014_Final.pdf

-

2020 scholarship and fellowship lists. Immigrants Rising. Accessed September 8, 2020. https://immigrantsrising.org/2020scholarships/

-

Rathmanner D. DACA financial aid options. Lendedu blog. April 3, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://lendedu.com/blog/daca-financial-aid/

- Venkataramani AS, Shah SJ, O’Brien R, Kawachi I, Tsai AC. Health consequences of the US Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) immigration programme: a quasi-experimental study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(4):e175-e181.

- Hainmueller J, Lawrence D, Martén L, et al. Protecting unauthorized immigrant mothers improves their children’s mental health. Science. 2017;357(6355):1041-1044.

- Kuczewski MG, Brubaker L. Medical education as mission: why one medical school chose to accept DREAMers. Hastings Cent Rep. 2013;43(6):21-24.

- Kuczewski MG, Brubaker L. Medical education for “Dreamers”: barriers and opportunities for undocumented immigrants. Acad Med. 2014;89(12):1593-1598.

- Kuczewski MG, Brubaker L. Equity for “DREAMers” in medical school admissions. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(2):154-159.

-

Lopez G, Krogstad JM. Key facts about unauthorized immigrants enrolled in DACA. Fact Tank. September 25, 2017. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/25/key-facts-about-unauthorized-immigrants-enrolled-in-daca/

- Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90-102.

-

Brief for Association of American Medical Colleges, et al as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Fisher v Univ of Tex at Austin, 133 S Ct 2411 (2013) (No. 14-981). Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/c/1/447744-aamcfilesamicusbriefinfishervutaustin.pdf

-

Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 24787. June 2018. Revised August 2019. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24787/w24787.pdf

-

Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. Adherence to cardiovascular disease medications: does patient-provider race/ethnicity and language concordance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1172-1177.

- Bibbins-Domingo K. This time must be different: disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(3):233-234.

-

Wasson K, Chaidez C, Hatchett L, et al. “We have a lot of power…”: a medical school’s journey through its New Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) initiative. Cureus. 2019;11(10):e6037.

-

Undocumented immigrants and the COVID-19 crisis. New American Economy. April 4, 2020. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/undocumented-immigrants-covid-19-crisis/

-

Svajlenka NP. A demographic profile of DACA recipients on the frontlines of the coronavirus response. Center for American Progress. April 6, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2020/04/06/482708/demographic-profile-daca-recipients-frontlines-coronavirus-response/

-

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). American Medical Association. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/population-care/deferred-action-childhood-arrivals-daca

-

American Dream and Promise Act of 2019, HR 6, 116th Cong, 1st Sess (2019). Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6

-

Jawetz T, Svajlenka NP, Wolgin P. Dreams deferred: a look at DACA renewals and losses post-March 5. Center for American Progress. March 2, 2018. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2018/03/02/447486/dreams-deferred-look-daca-renewals-losses-post-march-5/

-

National Immigration Law Center. Side by side: DACA and provisions of DREAM Act of 2019 and American DREAM and Promise Act of 2019. Updated June 22, 2019. Accessed May 4, 2020. https://www.nilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/DreamActs-and-DACA-comparison-2019.pdf