Abstract

Lack of disability-competent health care contributes to inequitable health outcomes for the largest minoritized population in the world: persons with disabilities. Health care professionals hold implicit and explicit bias against disabled people and report receiving inadequate disability training. While disability competence establishes a baseline standard of care, health professional educators must prepare a disability conscious workforce by challenging ableist assumptions and promoting holistic understanding of persons with disabilities. Future clinicians must recognize disability as an aspect of diversity, express respect for disabled patients, and demonstrate flexibility about how to care for disabled patients’ needs. These skills are currently undervalued in medical training, specifically. This article describes how integrating disability consciousness into health professions training can improve health equity for patients with disabilities.

Discomfort Providing Care for Patients With Disability

People with disabilities were estimated to compose 16% of the world’s population in 2021,1 making it inevitable that health care professionals will care for disabled patients, regardless of their practice location or specialization. Recent work demonstrates that physicians are hesitant about providing—and sometimes unwilling to provide—care for disabled patients.2 Additionally, medical students report greater discomfort when caring for disabled patients than nondisabled patients.3 These findings on current and future physicians’ perceptions suggest that the current disability curriculum in medical educational is insufficient. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated deeply entrenched ableism4 and clinicians’ negative beliefs about disabled patients,5 further contributing to health inequities for disabled patients.1 There is thus a significant need for radical change in pedagogical approaches regarding how we teach medical trainees about disability.

Competency-Based Curricula

Disability training across the medical education continuum is paramount to improving health equity. Nevertheless, medical students report that current disability education is inadequate to fully capture or contextualize the needs of disabled patients.3 Implementing the core disability competencies for health care education, proposed by the Alliance for Disability in Health Care Education,6,7 would guide curriculum development to provide students with disability-specific knowledge, skills, and beliefs needed to provide quality care. When taught, disability competencies increase both comfort and clinical skills in caring for disabled patients.7,8 However, competency-based education alone may not compensate for years of ableist education and experiences internalized by medical trainees. Indeed, a larger shift in medical education toward disability consciousness is needed.

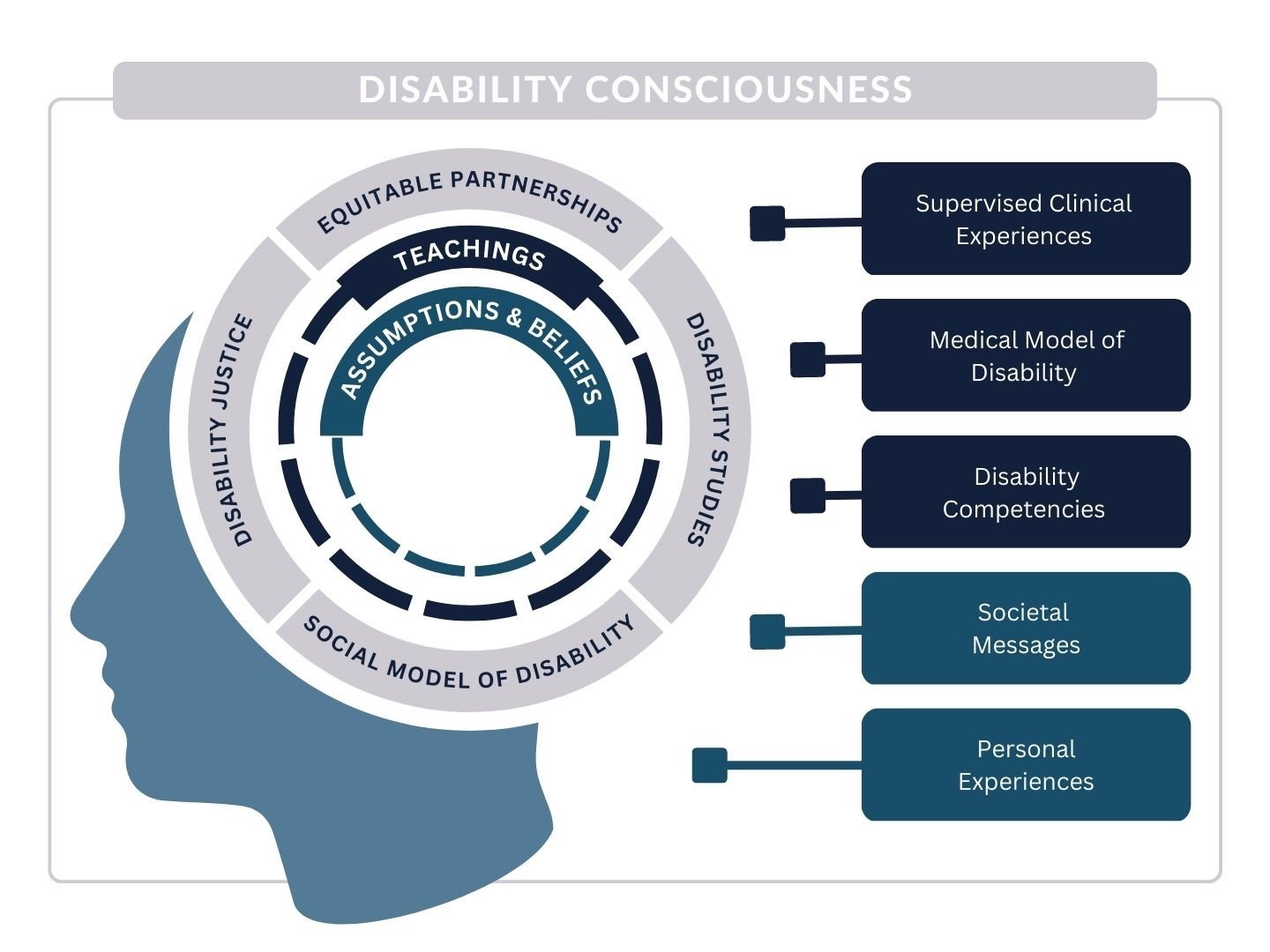

Disability competence introduced the notion of disability as an identity, similar to race, while a disability conscious curriculum leverages disability justice principles to help reframe trainees’ perspectives and cultivate openness in clinical reasoning.9,10 Specifically, disability consciousness utilizes disability studies to raise awareness of the historical violence and injustices against the disabled community and “more fully promote the respect, beneficence, and justice that patients deserve.”9 Disability consciousness adds an appreciation of the disability community’s broader lived experiences and can be conceptualized as a framework to interrogate the multiple ableist systems at play, thus leaving the learner better positioned to consciously employ a patient-centered approach (see Figure).

Figure. Model of Disability Consciousness Relative to Sources of Information, Educational Messaging, and Experiences That Shape Ableist Ideas

The inner ring highlights ableist assumptions and beliefs that are filtered through the middle ring of educational exposure and through an outer ring of disability consciousness.

What and How We Teach Matters

While the inclusion of disability topics in medical education presents an opportunity to counteract ableist assumptions, attention must be paid to what is taught and how it is taught. A recent study revealed that 82.4% of practicing US physicians believe that significantly disabled patients have a worse quality of life than nondisabled patients,5 an assumption discordant with disabled patients’ self-perceptions.11,12 The medical model of disability may perpetuate these inaccurate ableist assumptions by conceptualizing disability as merely a “health condition” and not as a marginalized identity of persons with unique lived experiences.13,14 Unfortunately, some students receive no disability training. A 2017 study found that only 52% of responding US allopathic and osteopathic medical schools included disability awareness programs.15 Many curricula are isolated, one-time lectures that fail to provide trainees with sufficient tools to approach disabled patients with a balance of knowledge and humility.16

Recently, disability-related humanities principles, disability rights education, and social model of disability topics have been embedded globally in Indian and Australian health professions education.17,18 In the United States, the commitment to the social model of disability is led by student advocates and faculty collaborators. For example, disability culture, the social model of disability, and direct interaction with disabled patients have been incorporated longitudinally in medical school curricula at Harvard Medical School,19 and similar topics are being piloted at Penn State College of Medicine and Ohio State College of Medicine (L. Smeltz et al, unpublished data, August 2023).20,21,22 Other US medical schools have similarly integrated disability rights and disabled patients as teachers into their curricula23 and advocated for universal design, or design with diversity and accessibility at the forefront, to be included as an educational topic and to guide curricula development. Positioning disabled people as teachers and including direct interactions with them in learning experiences have been well received by medical students and been shown to increase students’ and residents’ awareness, sensitivity, and preparedness to deliver high-quality care.24,25,26,27,28 Importantly, these curricula included topics related to the humanities and social and human rights to help students develop a holistic understanding of disability. Improving trainees’ recognition of implicit bias and increasing their confidence in assessing barriers to care will also help build disability-consciousness. In the future, as disability conscious health care professionals, they will continually navigate assumptions about disability and humbly partner with a growing population of diverse, disabled patients.

Anti-Oppressive Health Care

Discrimination, prejudice, and ableism are pervasive in health care. Mere individual recognition of differential treatment is insufficient to drive change,29 as the multi-layered medical training environment serves to uphold and reinforce deeply embedded ableist structures and attitudes. Fully addressing ableism, as well as related forms of oppressions such as racism, homophobia, trans-phobia, ageism, and sexism, will require flexibility, intentional curiosity, and a longitudinal commitment.

We believe that medical education should develop disability consciousness in health professions trainees. An idea that has been transformative in antiracism efforts,29 consciousness requires constant, active metacognition and reflection that lends itself to continual identity formation, skill development, open-minded thinking, and humility. Consciousness could be a novel vehicle for social change and for revolution in anti-ableist health care. Disability consciousness would lead transformation in health care by shifting the conception of disability from an individual and static view toward a holistic and dynamic view, allowing trainees to visualize how ableism permeates experiences at the individual, interpersonal, institutional, systemic, and structural levels. The disability conscious curriculum is supported by disability studies and disability justice principles that explicitly recognize disability’s unique culture and intersectionality with other identities. This heightened awareness is a critical step toward culturally responsive, comprehensive, and high-quality health care delivery.

Cultivating Humility

Including disability consciousness in training will add a layer of nuance and complexity to trainees’ awareness of disability, teach them to recognize and dismantle ableism at multiple levels, and ultimately help them develop the skills to apply adaptable, informed solutions to improve health equity for disabled people. For example, medical education has historically taught disability through the medical model, which views disability as a condition to be prevented, cured, or fixed,30 reinforcing ableist views. As mentioned, a disability conscious curriculum leverages disability justice principles to help reframe trainees’ perspectives and cultivate openness in clinical reasoning.

Trainees should aspire to develop respectful curiosity and seek ongoing engagement with disabled people. Just as disability consciousness learns from the fields of disability justice and disability studies, so clinicians must partner with and learn from others. This interprofessional team-based approach includes uniting with those in other disciplines and, most importantly, forming true partnerships with disabled patients and disabled physician colleagues. Collaborating on a team requires explicit focus on including diverse perspectives, which includes recognizing disability as part of diversity.31 Although increasing the representation of medical students and physicians with disabilities is a critical step toward promoting disability consciousness, from an ethical standpoint, we should be careful not to burden our minoritized colleagues by forcing them to constantly educate their colleagues.32 Similar to culturally responsive health care for other marginalized groups, approaching patient care with humility is essential for health equity. Humility underscores recognition of the need to practice self-awareness, acknowledge personal limitations, and seek continual growth. Therefore, we must, as a profession, fully address ableism and closely related forms of oppression with intentional curiosity and a longitudinal commitment. While anti-ableist health care is built on a foundation of competency, disability consciousness will lead us to an interprofessional, holistic understanding of the lived experience of disability.9

People with disabilities have historically been mistreated in health care, as evidenced by forced sterilization laws (upheld by Buck v Bell), institutionalization, and, most recently, the distribution of resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.33,34 Continuing to teach this information without behavioral and structural change is wrong. We have an ethical imperative to foster disability humility and better serve our disabled patients,35 and that duty starts with critically revamping the way we teach disability from the moment medical students begin their health care education.

“Conscious” Education

Medical education programs should partner with disabled people to build a curriculum and to develop experiences that cultivate trainees’ disability consciousness. Equitable inclusion of disabled people in health care is not only an ethical imperative but also improves learning.24,25,26,27,28 Collaboration with the disability community is a prerequisite to disability conscious curriculum development and directly combats inaccurate and damaging assumptions.

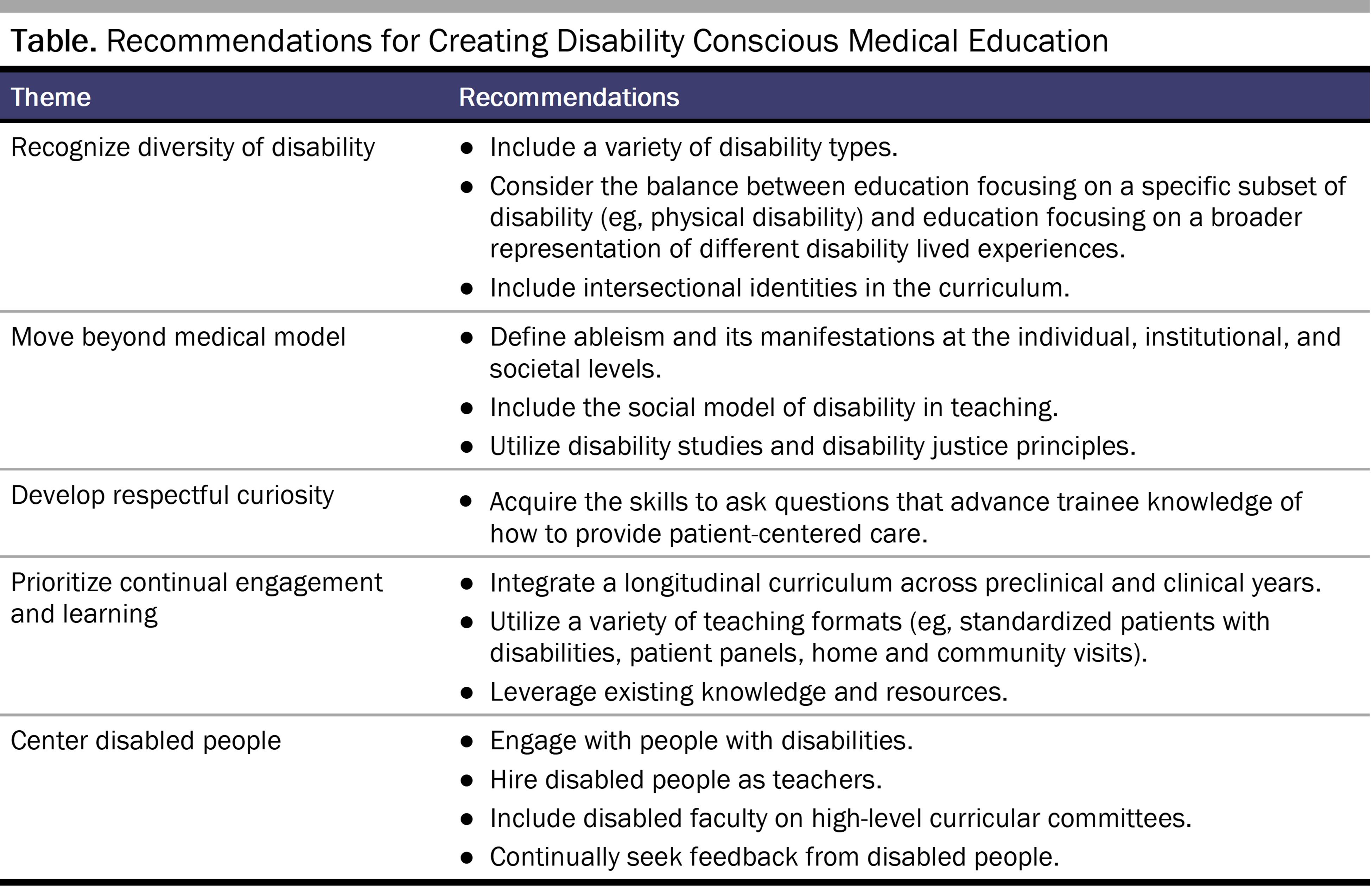

A disability conscious education would address each disability competency within the context of consciousness, necessitating the inclusion of the social and identity models of disability, disability studies, and disability justice (see Table). To implement these changes in medical education, educators need a standardized, interprofessional curriculum that is inclusive of diverse disability identities and that is explicitly informed and led by disabled people at all levels.

Preparedness and Progress

Trainees are increasingly pushing for a self-driven curriculum that prepares them to care for an increasingly diverse patient population, including a growing population of disabled patients. We acknowledge the work by student groups, federal agencies, and social justice movements—and agree that more training is needed. Unfortunately, progress has been incremental and slow.

The profession must approach disability conscious education with the same dedication, commitment, and vigor as other diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Disability is a valuable contributor to diversity and must be explicitly included under the goal of anti-oppressive, culturally responsive health care.

References

-

World Health Organization. Global Report on Health Equity for Persons With Disabilities. World Health Organization; 2022. Accessed August 29, 2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1481486/retrieve

- Lagu T, Haywood C, Reimold K, DeJong C, Walker Sterling R, Iezzoni LI. “I am not the doctor for you”: physicians’ attitudes about caring for people with disabilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(10):1387-1395.

-

Chardavoyne PC, Henry AM, Sprow Forté K. Understanding medical students’ attitudes towards and experiences with persons with disabilities and disability education. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(2):101267.

- Swenor BK. Including disability in all health equity efforts: an urgent call to action. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(6):e359-e360.

- Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):297-306.

-

Havercamp SM, Barnhart WR, Robinson AC, Whalen Smith CN. What should we teach about disability? National consensus on disability competencies for health care education. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(2):100989.

- Ratakonda S, Argersinger DP, Auchus GC, et al. A call for disability health curricula in medical schools. Trends Mol Med. 2022;28(12):1012-1015.

-

Lee D, Pollack SW, Mroz T, Frogner BK, Skillman SM. Disability competency training in medical education. Med Educ Online. 2023;28(1):2207773.

- Doebrich A, Quirici M, Lunsford C. COVID-19 and the need for disability conscious medical education, training, and practice. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2020;13(3):393-404.

- Couser GT. What disability studies has to offer medical education. J Med Humanit. 2011;32(1):21-30.

- Gerhart KA, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR, Whiteneck GG. Quality of life following spinal cord injury: knowledge and attitudes of emergency care providers. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(4):807-812.

- Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(8):977-988.

- Janz HL. Ableism: the undiagnosed malady afflicting medicine. CMAJ. 2019;191(17):E478-E479.

- Galli G, Lenggenhager B, Scivoletto G, Molinari M, Pazzaglia M. Don’t look at my wheelchair! The plasticity of longlasting prejudice. Med Educ. 2015;49(12):1239-1247.

- Seidel E, Crowe S. The state of disability awareness in American medical schools. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(9):673-676.

- Santoro JD, Yedla M, Lazzareschi DV, Whitgob EE. Disability in US medical education: disparities, programmes and future directions. Health Educ J. 2017;76(6):753-759.

- Bowley C, Furmage AM, Marcus K, Short SD. Case study: degree of integration of disability rights into allied health professional education. Health Hum Rights. 2018;20(1):259-272.

-

Singh S, Khan AM, Dhaliwal U, Singh N. Using the health humanities to impart disability competencies to undergraduate medical students. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(1):101218.

-

Yirga A, Beyer L, Patt E, Tolchin DW. Including disability in the equity and diversity conversation: honing advocacy skills through curriculum development. J Harv Med School Acad. 2022;2(3). Accessed March 30, 2023. https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/jhmsa-vol2-issue3/including-disability-equity-and-diversity-conversation-honing-advocacy-skills

-

Smeltz L, Carpenter S, Benedetto L, et al. ADEPT-CARE: a pilot, student-led initiative to improve care for persons with disabilities via a novel teaching tool. Disabil Health J. 2023;16(3):101462.

-

Crane JM, Strickler JG, Lash AT, et al. Getting comfortable with disability: the short- and long-term effects of a clinical encounter. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(2):100993

- Havercamp SM, Ratliff-Schaub K, Macho PN, Johnson CN, Bush KL, Souders HT. Preparing tomorrow’s doctors to care for patients with autism spectrum disorder. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2016;54(3):202-216.

- Bosques G, Ankam NS, Kasi R, et al. Now is the time: a primer on how to be a disability education champion in your medical school. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;101(1):89-96.

- Jain S, Foster E, Biery N, Boyle V. Patients with disabilities as teachers. Fam Med. 2013;45(1):37-39.

-

Minihan PM, Bradshaw YS, Long LM, et al. Teaching about disability: involving patients with disabilities as medical educators. Disabil Stud Q. 2004;24(4).

-

Selick A, Durbin J, Casson I, et al. Improving capacity to care for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities: the value of an experiential learning model for family medicine residents. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(3):101282.

-

Edwards AP, Cron S, Shonk C. Comparative effects of disability education on attitudes, knowledge and skills of baccalaureate nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;61:103330.

-

Marzolf BA, Plegue MA, Okanlami O, Meyer D, Harper DM. Are medical students adequately trained to care for persons with disabilities? PRiMER. 2022;6:34.

-

Kendi IX. How to Be an Antiracist. One World; 2023.

-

Crow L. Including all of our lives: renewing the social model of disability. In: Morris J, ed. Encounters With Strangers: Feminism and Disability. Women’s Press; 1996:206-226.

- Agaronnik ND, Saberi SA, Stein MA, Tolchin DW. Why disability must be included in medical school diversification efforts. AMA J Ethics. 2021;23(12):E981-E986.

- Iezzoni LI. Why increasing numbers of physicians with disability could improve care for patients with disability. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(10):1041-1049.

- Smeltz LR, Carpenter SL. Reflecting on health inequities in a global pandemic: the need for disability-conscious public health strategies. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(4):592-594.

- Johnson E. Disability, medicine, and ethics. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(4):355-358.

- Reynolds JM. Three things clinicians should know about disability. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(12):E1182-1188.