As a child, I (T.O.) was a voracious consumer of comics. While my parents would dissect out their sections of interest from the Sunday paper, the “funnies” were always set aside and reserved for me. I collected Garfield, Calvin and Hobbes, and Batman comic books, which I would read in my favorite pair of red Dick Tracy pajamas. My mother was an art teacher, so art appreciation and creation were prominently cultivated in my household. For me, the comics I loved were always unquestionably considered a true art form on par with other fine arts. Comics drew me in due to their aesthetic appeal, with their bold colors and expressive characters. What kept me hooked on comics was that these stories allowed for total immersion in the minds and worlds of the characters, offering me a broader experience as a reader than I had with other modes of storytelling.

When I enrolled at Penn State College of Medicine, I was thrilled to discover a course focused on medically themed graphic narratives being offered as a part of the school’s medical humanities curriculum. Studying medicine through the lens of comic art felt like a course specifically designed for me. The course was created by Michael J. Green, a physician and bioethicist who helped pioneer the field of graphic medicine. The term “graphic medicine,” coined by Ian Williams, a British physician [1], refers to the intersection of comics and health care discourses [2]. Green’s class was the first medical school course to teach graphic narratives as a part of medical education, and it opened my eyes to this emerging field.

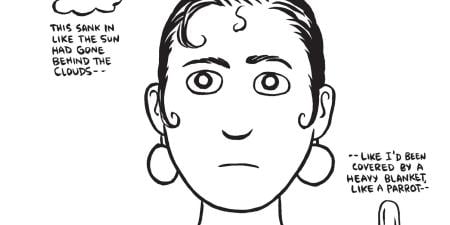

Many readers might be surprised that comics are being taught in medical school. How can a medium most closely associated with the capers of spandex-clad superheroes possibly address serious topics of health and illness? People are familiar with the historical association of comics with juvenile entertainment or underground movements, but comics are no longer only for children and fringe subcultures. Comics have evolved substantially since the Comics Code was adopted in 1954 [3]. Sparked primarily by the writings of Fredric Wertham, a physician who believed reading comics lead to juvenile delinquency [4], the Comics Code censored comics, setting out rules for permissible content. To be published, comics were required to minimize violence and sex. They were also required to demonstrate respect for authority [1, 2]. These days, comics address every conceivable topic, ranging from the experiences of Holocaust survivors to life growing up during the Iranian Revolution [5-7]. Not surprisingly, comics have also found their way into the medical field through accounts by patients (e.g., Cancer Made Me a Shallower Person: A Memoir in Comics[8]), clinicians (e.g., The Bad Doctor: The Troubled Life and Times of Dr. Iwan James [9]), and caregivers (e.g., Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me [10]).

This issue of the AMA Journal of Ethics addresses comics as they apply to medical ethics. It explores a range of issues in using comics in medical education and clinical practice, including as tools for patients and for conveying the experience of illness. Taking a historical perspective, Carol Tilley addresses how the representation of clinicians in comics has changed over time and, in particular, how such portrayals are becoming increasingly realistic. As the comics field diversifies, so does the way clinicians are depicted, a trend that will likely continue to evolve over the next decade.

Three contributions address the role of comics in educating the public. MK Czerwiec writes about social and political activism related to HIV/AIDS, focusing on the role played by comics in health education. Susan M. Squier takes on a related theme, addressing issues of social justice in the development of drugs for the poor in resource-poor countries. In particular, she explores how the educational comic Parasites! offers an alternative to the profit motive by emphasizing social and ethical concerns related to drug development in under-resourced countries. In the podcast, Brian Fies and Phoebe Potts discuss their experiences as the authors of graphic novels that deal with health care issues and explain why graphic medicine provides a uniquely powerful medium for communicating about challenging topics in health care.

The concept of graphic pathographies—illness narratives in graphic form [1]—are explored by several authors. Kimberly R. Myers and Michael D.F. Goldenberg show how graphic pathographies have become powerful tools for health care professionals seeking insights into patients’ lived experience of illness and the benefits of these depictions for health professions students and patients alike. Mark Tschaepe shows in particular how graphic narratives can illuminate patients’ experiences of autonomy. Using a specific example of graphic pathography focused on a teen with mental illness, Swallow Me Whole, Jared Gardner argues that the reader’s participation in making meaning provides a model for collaboration among patients, clinicians, and caregivers. Linda S. Raphael and Madden Rowell explore the representation of those with illness or disability, arguing that examining patients’ and clinicians’ subjective experience of careunderscores the importance of treating patients with dignity, compassion, and respect.

In recent years, comics have been incorporated into formal medical school curricula around the world. Using an original comic created by Mónica Lalanda, Lalanda, along with Rogelio Altisent and Maria Teresa Delgado-Marroquín, describe how a written code of ethics was transformed into an effective comic to teach medical students. Jeffrey Monk focuses on the topic of abusive treatment of medical students using a comic he created when enrolled in a graphic medicine course as a medical student. He contends that comics can be a safe space for expression and for sharing experience and hence are an effective medium for addressing this sensitive issue. Megan Yu discusses the skills and attitudes that medical students can learn from reading and creating comics as well as the ethical challenges of using student-generated comics in teaching.

Comics are not only being used to educate medical students but also as effective patient education tools. Gary Ashwal and Alex Thomas discuss the appropriateness of comics as patient educational materials, arguing for the importance of ensuring accuracy of information, respecting patients’ preferences for educational format, and presenting comics in a sensitive manner.

Comics can no longer be dismissed as “low-brow” and unworthy of scholarly exploration. They have become part of the educational environment and can provide meaningful commentary about the social, cultural, and ethical landscape where patients, caregivers, clinicians, and learners intersect. It is our obligation to critically evaluate these works and address some of the uncomfortable questions they raise. This issue of AMA Journal of Ethics on comics in medicine aims to increase awareness of and further legitimate these works while beginning to address head-on some of the ethical issues surrounding their use.

References

-

Green MJ, Myers KR. Graphic medicine: use of comics in medical education and patient care. BMJ. 2010;340:c863. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c863.

-

Williams I. Why “graphic medicine”? Graphic Medicine. https://www.graphicmedicine.org/why-graphic-medicine/. Accessed December 5, 2017.

-

Versaci R. This Book Contains Graphic Language: Comics as Literature. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group; 2007.

- Tilley CL. Seducing the innocent: Fredric Wertham and the falsifications that helped condemn comics. Inf Cult. 2012;47(4):383-413.

-

Weiner S. Faster Than a Speeding Bullet: The Rise of the Graphic Novel. New York, NY: Nantier Beall Minoustchine; 2003.

-

Spiegelman A. The Complete Maus. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 1997.

-

Satrapi M. The Complete Persepolis. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 2007.

-

Engelberg M. Cancer Made Me a Shallower Person: A Memoir in Comics. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 2006.

-

Williams I. The Bad Doctor: The Troubled Life and Times of Dr. Iwan James. Brighton, UK: Myriad Editions; 2014.

-

Leavitt S. Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Freehand Books; 2010.