Abstract

This essay argues that we should judge the illustrations in a graphic novel (often a memoir) in the context of the entire work. Judging a work on its emotive effects and the values it expresses, we can consider the ways a graphic novel represents the experience of illness, disability, or injury.

Introduction

Reading a graphic novel involves a lot of work; images and words can give similar messages or suggest different interpretations. The reader needs to pay attention to the “gutter”—the empty spaces between frames that the reader almost unconsciously fills—and take note of the size of frames. Artists create splash pages in which only one scene or image is depicted; they might organize the page with similarly sized panels or large and small ones. Generally, large panels indicate that the image or the words are especially important.

Graphic medicine novels feature characters who often experience illness or injury, which therefore makes yet another demand on a reader. That demand—that the reader judge the ethical import of the drawings and words—is complex. For example, Kathryn Harrison’s confessional memoir The Kiss: A Memoir [1], can be analyzed in terms of whether Harrison seeks to sensationalize her sexual relationship with her father or seeks understanding of her experience. Readers might ask similar questions about Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic [2], a graphic novel that explores her father’s sexual relationships with his high school students, his apparent suicide, and her own “coming out.” The questions we ask can be asked of graphic and nongraphic texts alike; however, the illustrations raise and often answer different questions than nongraphic text.

In this essay, we argue that three principles, suggested by James Phelan in Living to Tell about It: A Rhetoric and Ethics of Character Narration [3], prove to be useful in judging the ethical nature of not only “words-alone” texts but also graphic novels:

- The cognitive dimension. What do we understand and how do we understand it?

- The emotive dimension. What do we feel, and how do those feelings come about?

- The ethical dimension. What are we asked to value in these stories, how do these judgments come about, and how do we respond to being asked to take on these values and make these judgments?

The responses to these questions might differ among readers; however, we believe that the above considerations are helpful to anyone who attempts to make the complex judgments graphic novels ask of us.

The Author as Central Character in the Graphic Novel or Memoir

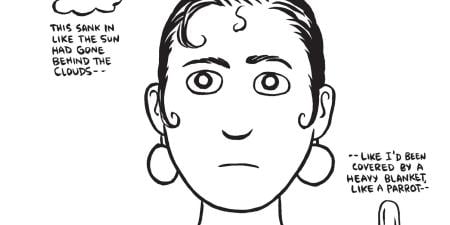

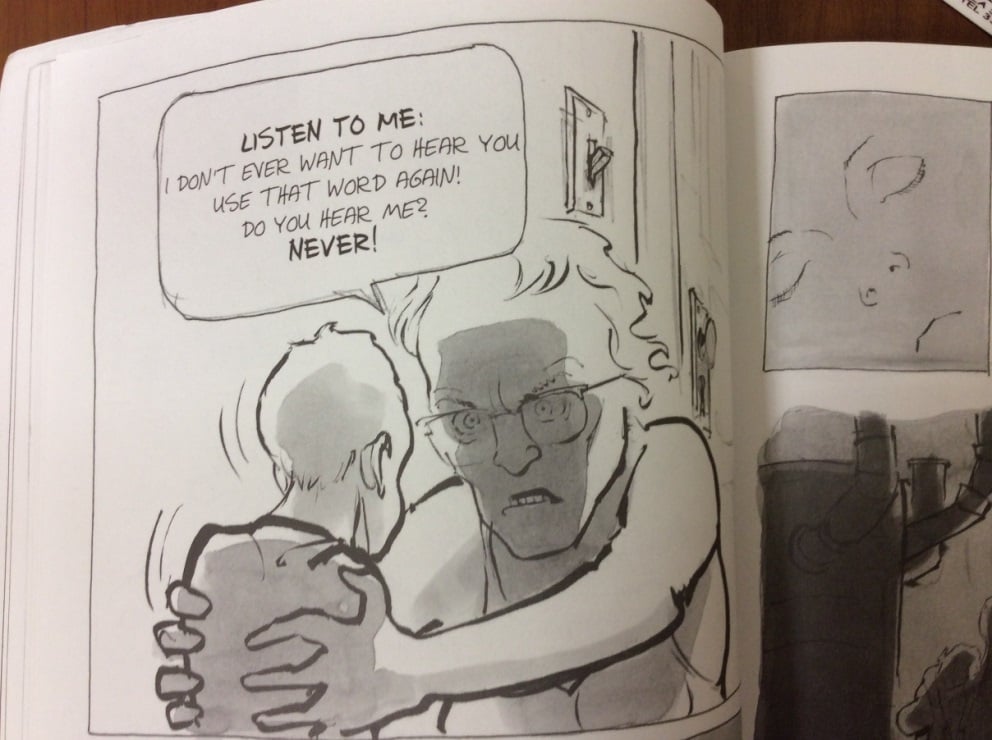

David Small’s autography, Stitches: A Memoir [4], raises some questions about how we understand the revelation of David’s parents’ and his grandmother’s mistreatment of him. We know that David’s childhood was unhappy; his patents and his grandmother mistreated him; his mother was an alcoholic who was secretly a lesbian; his father was a radiologist whose decision to give David x-ray treatments for his throat problems led to throat cancer. The reader likely feels angry at the parents and grandmother and sad for David. As we see in figures 1-3, the small child is helpless in the face of cruel or careless adults.

Cognitive dimension. The varied size of the panels and frequent absence of words illuminate some of the above meanings. In figure 1, where David’s maternal grandmother drags him up the stairs by his wrists, the full panel indicates, “This is very important!” Figure 2, a half-page panel, shows David alone on the bathroom floor immediately afterwards. Figure 3, a smaller panel that offers a close-up of the faces of David and his father when the former complains about his grandmother, focuses the reader on the father’s rage. The story is not only about the abuse David suffered at the hands of his grandmother but also about his radiologist father administering x-ray treatments to his throat, which caused him to lose his voice. Clearly, visual over verbal expression “speaks” to David’s experiences.

Figure 1. Excerpted from Stitches

Copyright © 2009 by David Small. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 2. Excerpted from Stitches

Copyright © 2009 by David Small. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 3. Excerpted from Stitches

Copyright © 2009 by David Small. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Emotive dimension. These frames depict emotions of fear and anger; the values that are represented by their absence are respect and restraint. The visual representation of the small child next to his father, whose large hands encompass almost all of David’s upper back, reinforces the sense of helplessness that David’s tale evokes. David only occasionally narrates his story outside the dialogue in the frames, but emotions, values, and judgments find expression.

Ethical dimension. Through illustrations, David is able to avoid using a child’s language to report what would be beyond his younger self’s ability to express; the reader enters into the child’s experience through visual depictions of the child’s fear, the grandmother’s cruelty, and the father’s rage without attributing to the young David thoughts beyond his expressive capability or, alternatively, inserting David’s adult judgment. The reader therefore makes her own ethical judgments of David’s situation. Take, for example, David’s father’s medical treatment of his son. Generally speaking, physicians are advised against treating their own family members [5]. The ethical question of whether David’s father did the right thing by administering radiation to his throat cannot be answered solely by the effects of the radiation since outcomes do not necessarily determine the ethics of an action. Rather, David’s father’s raging behavior, depicted in figure 3, suggests that his medical treatment of his son may have been as poorly considered as his general treatment of his son.

Interpreting the Patient’s Experience

Although it seems obvious that the patient is the central person in her illness narrative, well-meaning physicians might lose sight of this fact as they seek to provide the best treatment they can based on their own medical knowledge and that of other physicians. In a recent instance, the second author (MR) noted that her attending physician coached a medical student on her team not to present patients’ explanation for their symptoms but simply the symptoms themselves: “We know that her lack of appetite is from her cancer-related pain, not from sitting in her hospital bed like she said to you. Patients always come up with explanations for their symptoms … that aren’t always correct.” The resident worried that the practice of separating patients’ explanations from their symptoms has become second nature. She noted that she had written “patient reports subjective fever, but temperature afebrile on exam” countless times. She expressed concern over being constantly reminded to separate the subjective from the objective and, in some cases, to ignore the patient’s subjective experience altogether.

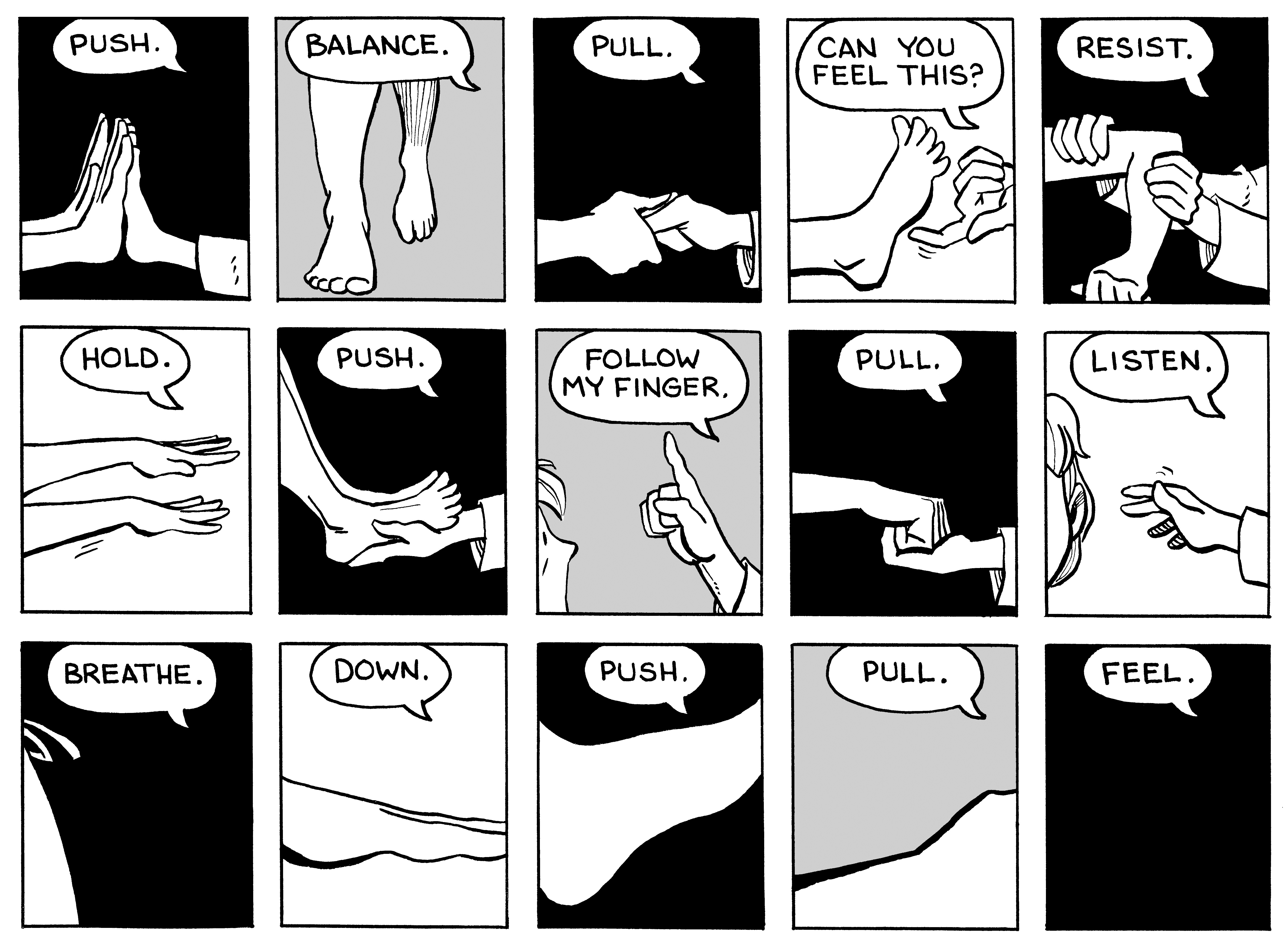

Graphic novels take the patient’s experience of illness and infuse it directly into the medium of expression. The narrative of a patient or family member cannot be manipulated with words or transformed into medical jargon; it is there in 2D without apology. In Mom’s Cancer [6], after a caption that reads, “The exams begin,” Brian Fies breaks the physical exam into many small frames, each containing an action and a command (see figure 4). These frames portray the patient’s subjective experience of the physical exam, highlighting how, for the patient, these mysterious movements can reduce her to only a body in our search for objective data.

Figure 4. “The Exams Begin,” from Mom’s Cancer

© 2006 Brian Fies. Reprinted by permission of Brian Fies.

These frames suggest the subtle indignities that Mom experiences without her author-son’s interpretation. Drawing only the foot suggests the treatment of a patient as a bundle of parts. The images call for empathic emotions; they highlight the value of empathic treatment of the other—missing here—by carefully informing a person about things being done to her body. Graphic novels are thus an important reminder to clinicians that subjective experience and objective data are not always so cleanly divided into two separate entities. While patients might feel objectified, our objective data are colored by the language we use, our level of fatigue or compassion in any given moment, our teachers, and our culture.

Health Care Professionals as Graphic Artists

The graphic novels of two health care professionals, MK Czerwiec and Ian Williams, offer yet other ways to think about the ethical import of illustrations. In Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Unit 371 [7], Czerwiec records her experience working in a hospital AIDS unit in 1994 in words and in illustrations she describes as “simple.” Yet her recounting of the experience is anything but simple. In fact, her style tends to make the characters look similar, suggesting the complexity of the relationship. Czerwiec’s book expresses empathy for her patients and pain at losing them (see figures 5 and 6). Perhaps this is part of “taking turns.” Often patients are surprised and even dismayed when their clinicians become ill or die. They see them as invulnerable, a view that is sometimes matched by that of the clinician herself. In Taking Turns this view is overturned.

Figure 5. Excerpted from Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371

© 2017 MK Czerwiec. Reprinted by permission of MK Czerwiec.

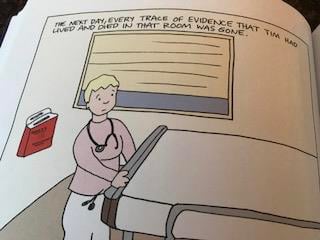

When Czerwiec’s patient Tim dies, Czerwiec stands at his bed expressing in words the absence of a person who still seems so immediately present (see figure 6). The illustration symbolizes loss and encourages the reader to value the friendship that Czerwiec and Tim shared. The novel thus expresses values for human communication, closeness, and the ways that deep caring about others can play a significant role in the lives of those who give the care as well as those who receive it.

Figure 6. Excerpted from Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371

© 2017 MK Czerwiec. Reprinted by permission of MK Czerwiec.

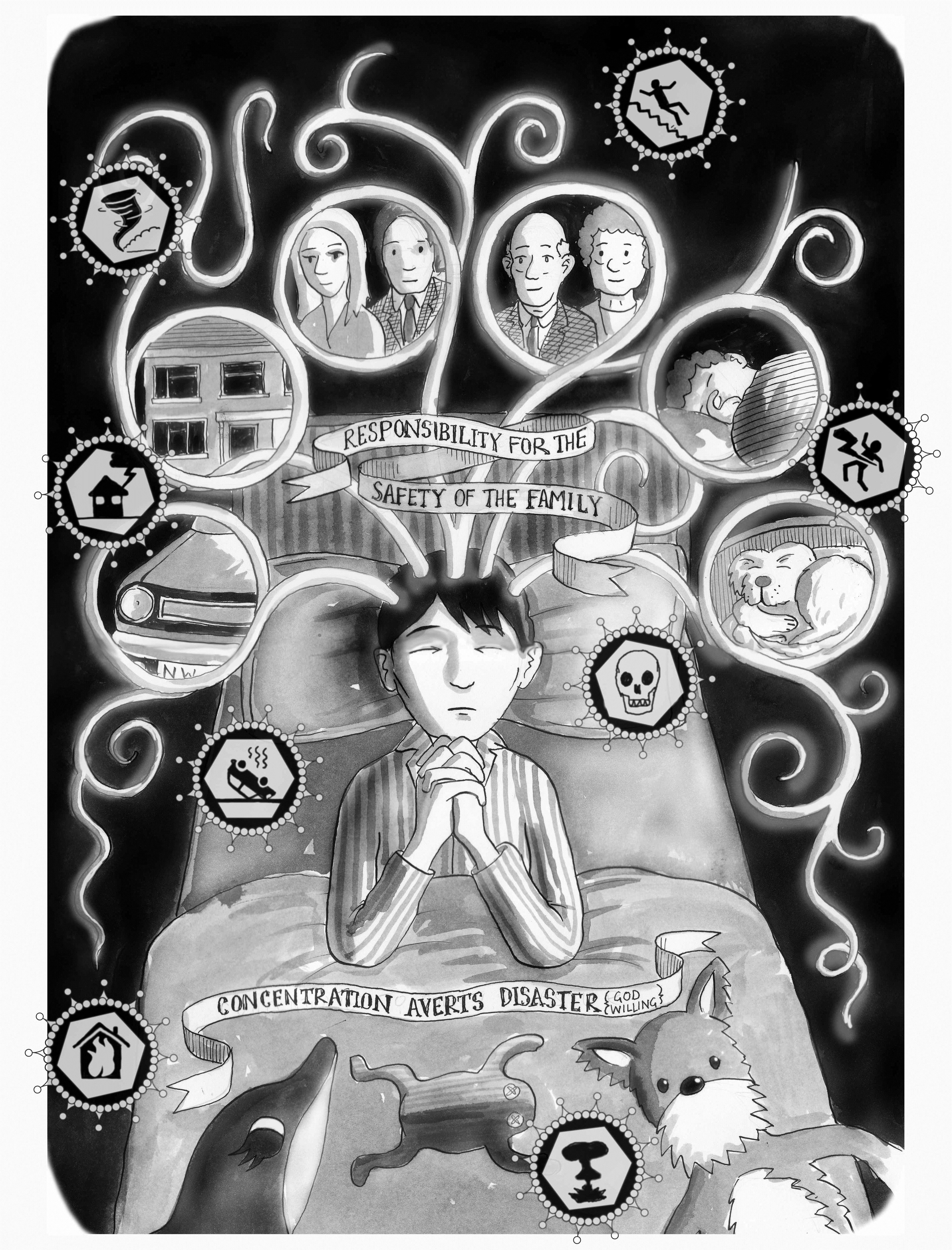

The illustrations of both Ian Williams (see figure 7) and Czerwiec bring to mind the words of the German cartoonist, Erich Ohser, who was internationally famous for his comic strips in the 1930s. He spoke about the aesthetics of comics in his 1943 In Defense of the Art of Drawing.

If you draw, the world becomes more beautiful, far more beautiful. Trees that used to be just scrub suddenly reveal their form. Animals that were ugly make you see their beauty. If you then go for a walk, you’ll be amazed how different everything can look. Less and less is ugly if every day you recognize beautiful forms in ugliness and learn to love them…. A small drawing that comes from the eye and the heart is worth more than sixty square feet of inhibited, dishonest hack work [8].

While Czerwiec’s drawings offer a simplistic beauty, Williams, a physician, draws more elaborately. In The Bad Doctor: The Troubled Life and Times of Dr. Iwan James [9], the story of a physician who has experienced symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder since childhood, Williams includes a complex drawing that seems to draw on the Kabbalah’s ten Sefirot or manifestations of God [10] by offering the reader multiple representations of illness by the patient and the doctor himself (see figure 7). The tension between the mortal and the infinite, represented in the Kabbalah and in Williams’s drawing, corresponds to Ohser’s idea that the world is made more beautiful in sincere illustrations.

Figure 7. Excerpted from The Bad Doctor: The Troubled Life and Times of Dr. Iwan James

© 2014 Ian Williams. Reprinted by permission of Ian Williams.

Conclusion

We have offered examples in this essay of how illustrations in graphic medicine texts create or augment meanings that the narrator could not express (Stitches), experiences that patients endure (Mom’s Cancer), and the relationship between a patient and nurse (Taking Turns). Each of the graphic medicine novels to which we refer has ethical implications for patient care and the patient-physician relationship, and, in each case, the illustrations do much of the work in developing these ethical implications.

References

-

Harrison K. The Kiss: A Memoir. New York, NY: Random House; 1997.

-

Bechdel A. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2007.

-

Phelan J. Living to Tell about It: A Rhetoric and Ethics of Character Narration. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2005.

-

Small D. Stitches: A Memoir. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 2009.

-

American Medical Association. Opinion 1.2.1 Treating self or family. Code of Medical Ethics. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/treating-self-or-family. Accessed December 15, 2017.

-

Fies B. Mom’s Cancer. New York, NY: Abrams ComicArts; 2011.

-

Czerwiec MK. Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press; 2017.

-

Schulze E. Beloved and condemned: a cartoonist in Nazi Germany. New York Review of Books. September 14, 2017. http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/09/14/beloved-and-condemned-a-cartoonist-in-nazi-germany/. Accessed October 17, 2017.

-

Williams I. The Bad Doctor: The Troubled Life and Times of Dr. Iwan James. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press; 2015.

- Fishbane EP. The speech of being, the voice of God: prophetic mysticism in the Kabbalah in Asher ben David and his contemporaries. Jew Q Rev. 2008;98(4):485-521.