Abstract

America faces widespread gun violence and police brutality against Black citizens and persons with severe mental illness (SMI). Violence perpetrated against unarmed patients is common in health care, and evidence-based safety measures are needed to acknowledge and eradicate clinical violence. Community mental health centers (CMHCs) serve many patients of color and persons with SMI, so their overreliance on police or building security deserves ethical and clinical consideration. Policing of Black persons’ health care begins in powerful, false narratives that White persons need protection from dangerous Black citizens who reside in urban areas or who have mental illness. This article considers White supremacist origins of the myths making CMHCs sites of policing and trauma rather than safety and healing and offers recommendations for advancing policy and practice.

Intersections of Healing and Violence

Social justice movements against police brutality and killings of unarmed Black citizens like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor have prompted the medical community to recognize White supremacy’s role in inflicting physical, social, and mental health trauma upon people of color,1,2 especially Black Americans, whom racial trauma and police violence most directly impact.3 As academic public psychiatrists, we believe that community mental health centers (CMHCs) should lead the medical community by example in healing racial and police trauma through depolicing.

There are over 2500 CMHCs in the United States providing care to over 1 million people, with many of those served having severe mental illness (SMI).4 A disproportionately high number of Black people receive care from CMHCs in inpatient, outpatient, and residential settings (19%, 16%, and 31% of clients, respectively) relative to their share of the population (13.4%).4 CMHCs also commonly perform citywide mobile mental health crisis calls, which unfortunately often involve armed police.5 Indeed, an estimated 25% of police shooting deaths involve mental health crises,6 with people with untreated mental illness being 16 times more likely to be killed by police than other civilians who interact with police.6 Moreover, 12% of patients have police involved in their transportation to mental health services.7 Because CMHCs serve a high proportion of people of color and persons with SMI, they are thereby positioned at the forefront of healing racial and police trauma.

Nevertheless, there are barriers to CMHCs serving as an example of depolicing in medicine. Mass fear of gun violence in America,8 along with actual high rates of unarmed workplace violence in health care, makes clinicians concerned for their safety and predisposes them to anxiety, trauma, and burnout.9 While a degree of fear of workplace violence is understandable, health care personnel may be overestimating perceived risk of armed health care violence.10,11 Also problematic is the lack of efficacy of health care policing for ensuring safety in care settings. Furthermore, reliance upon police and security is inconsistent with medical institutions’ position statements that commit to upholding antiracist and antibias principles opposing gun violence and police and racial trauma. For example, a 2018 position statement by the American Psychiatric Association denounces the presence and use of weapons during unarmed clinical or behavioral emergencies.12

Frontline Clinicians to Marginalized Communities

One reason CMHCs serve so many clients with low income is because upstream mechanisms of insurance reimbursement introduce disparities in access to psychiatric professionals.13,14 Insurers frequently maintain noncompetitive psychiatric reimbursement rates that disregard exceedingly high psychiatric demand. Thus, many psychiatrists do not accept insurance at all.14 Additionally, a 2019 study found that psychiatrists were half as likely as primary care physicians to accept new Medicaid patients (35.43% vs 71.29%, respectively) during 2014 to 2015.13 As such, CMHCs are safety net providers to persons with Medicaid or Medicare and to the uninsured, all of whom cannot access a wider selection of mental health workers due to reimbursement disparities.

CMHCs are often the only option for persons of color and persons with SMI who, due to legacies of White supremacy and bias against mental illness, cannot afford private health insurance. Black communities have been fighting systemic educational, employment, financial, carceral, and countless other obstacles imposed by White supremacy for over 400 years.15 These factors sustain the unremitting poverty of persons of color that is reflected in their overrepresentation among the uninsured,16 and states that declined Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act disadvantaged Black Americans most.16 Persons with SMI are vulnerable to downward socioeconomic drift, with social determinants exacerbating their mental health issues.17

Myths of Urban Dangerousness

White supremacy and bias against mental illness not only perpetuate the aforementioned barriers to mental health care access but also influenced the advent of health care policing, particularly at teaching and urban hospitals. Nearly 30 years ago, one national survey of 248 emergency departments (EDs) found that teaching hospitals were almost twice as likely to have in-house security as nonteaching hospitals (43.5% vs 24.7%, respectively), and 3 of the 4 hospitals using metal detectors at the time were teaching hospitals.18 Furthermore, urban centers were 2.4 times more likely to have 24/7, in-house security as rural centers, and 3 of the 4 hospitals using metal detectors were in urban locations.18 Today, armed security is “nearly always greater” at large and public (often urban) hospitals.19 One must wonder whether heightened security at urban and teaching hospitals arose to protect predominantly White-bodied trainees20 and clinicians from the presumed dangerous bodies occupying urban spaces—bodies more likely to be of color.

Police brutality is a social determinant of health that fosters mistrust in medical institutions and is associated with victims’ greater likelihood of unmet medical needs.

Although hospitals serving largely Black populations are most likely to be policed, a study of hospital-related shootings from 2000 to 2011 did not find inner-city locations or “dangerous” neighborhoods to have higher incidences of hospital violence.11 Of interest, the authors also calculated a greater likelihood of being struck and killed by lightning than being a victim of a hospital shooting.11 Furthermore, a 2018 study of metal detector implementation at EDs across a large hospital system found that hospitals with the most Black patients confiscated the fewest weapons, whereas the hospitals with the most White patients confiscated the most weapons.21 The prevalence of metal detectors and armed security at urban, academic, public institutions serving large proportions of people of color therefore contradicts data on where need for screening is highest. These policies, therefore, seemingly arise from White supremacist myths of Black urban dangerousness.

Myths of Psychiatric Dangerousness

Media coverage often falsely equates persons with SMI with perpetrators of violence, while also promoting White supremacy by broadcasting sympathetic portrayals of White shooters vs violent portrayals of perpetrators of color.22 Stereotyping persons of color and persons with SMI as violent may foster mistaken beliefs that additional security measures within CMHCs and in responding to mobile crisis calls are warranted. Deinstitutionalization unfortunately may have reinforced these stereotypes by fostering the criminalization of mental illness and increasing homelessness, leading to jails and prisons serving as de facto mental health facilities.23 Indeed, a 2021 study found that reducing the number of local psychiatric inpatient beds contributed to subsequent increases in the number of people jailed regionally.24 Stereotypes of violence may also be reinforced by the disproportionate levels of policing and criminalization experienced by people of color: Black individuals are significantly more likely than White individuals to be stopped by police, charged with more serious crimes, arrested for drug-related charges despite lower overall drug use, and sentenced more harshly.25,26 The confluence of anti-Black bias, anti-SMI bias, and actual—although rare—episodes of armed workplace violence conspire to make those treated at CMHCs very vulnerable to myths of dangerousness.

Policing Outpatient Mental Health

Policing measures are implemented with the idea of reducing health care violence, but it is worthwhile to briefly note that armed officers and metal detectors do not consistently reduce health care violence. Many hospital shootings occur outside the hospital itself or immediately beyond the perimeter of screening with metal detectors, like an ambulance ramp, thereby easily circumventing detection by screening.11 Additionally, confiscating more weapons with metal detectors has not been shown to automatically equate with reducing health care assault,27 as determined shooters are less likely to be deterred by metal detectors.11 Finally, the presence of armed officers may actually introduce as many shootings as it eliminates: half of ED shootings would not have occurred were it not for the firearm being carried by security personnel themselves.11

Moreover, the risk of workplace violence in outpatient settings is attributable to factors beyond lack of security. In a 2020 systematic review of studies on outpatient workplace violence conducted by survey and interviews with victims, violence was commonly attributed to clinic-based factors, such as unmet service needs, misunderstanding between patient and clinician, and overcrowding of the clinic or long wait times.28 These findings suggest that addressing workplace violence strictly by directing security measures toward people with mental illness is misguided and, furthermore, that responses to inhumane and inadequate medical care may be pathologized as violence or mental illness. Of note, this review did not find a single study conducted in the United States, which draws attention to the fact that there is no evidence base for policing practices commonly employed in outpatient clinics in this country.

Other data limitations regarding outpatient health care violence are noteworthy. Most studies examining health care violence were conducted in large-scale hospitals, EDs, and inpatient units.11,18 CMHCs are, by definition, predominantly outpatient settings serving less acute patients than most hospital settings. Caution is warranted when generalizing hospital-based risk and safety data to outpatient settings like CMHCs.

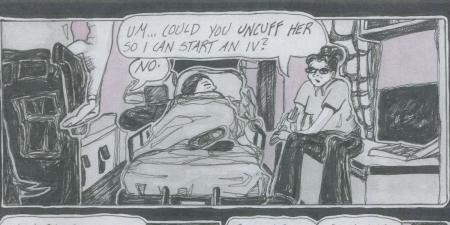

In the authors’ experience as academic public psychiatrists, CMHCs more often implement police and security measures, including metal detectors and lethally armed officers, than clinics catering to those who pay in cash and the privately insured. Such practices disregard their ethical obligations of nonmaleficence29 by iatrogenically inflicting psychological and physical harm as well as stigma upon clients with preexisting police and racial trauma—all in the name of “safety.” Otherwise stated, outpatient providers and organizations purportedly practicing trauma-informed care invest in policing operations while accepting injury to clients. Yet, the “necessity” and “efficacy” of these discriminatory acts have no scientific basis. Policing CMHCs was never evidence based, and social justice movements provide a necessary culturally responsible, historically corrective path forward.

Depolicing Medicine

Although it is important to acknowledge how context influences fears of health care workplace safety, policing practices in CMHCs and mobile crisis interventions may represent non-evidence-based legacies of White supremacy, prejudice against persons with SMI, and policing bias against persons with mental illness and persons of color. Police brutality is a social determinant of health that fosters mistrust in medical institutions and is associated with victims’ greater likelihood of unmet medical needs (eg, doctor’s visits, tests, procedures, prescription medication, and hospitalizations).30 It follows, then, that unjust policing of people of color with SMI may likewise foster this group’s medical mistrust and unmet medical needs while also negatively affecting the mental health of those exposed to this unjust policing.31

In the wake of George Floyd’s killing and COVID-19 inequalities, robust federal funding to remove police from mental health crisis interventions has been prioritized for the first time.32 Antiracism and antibias demand that we prioritize the comfort of those we serve rather than our own sense of security, which will require yielding historically predominantly White decision-making positions to medical faculty of color as well as community members, activists, and persons with lived experience of violence and mental illness. We must learn from and replicate models of depolicing mental health interventions (eg, the mobile crisis program CAHOOTS in Oregon33) as well as liaison directly with community members and community activist groups to lift up their voices and demand depoliced communities and health systems.34

Antiracist praxis may be best accomplished by incorporating and listening to the voices of leaders within communities of color. As clinicians, we can amplify their voices by critically examining data through a historically and culturally corrective lens that truly challenges long-held beliefs, assumptions, and frank myths behind facility policies that uphold the overpolicing of institutions. For example, data presented in this article reveal that metal detectors are implemented in a racialized manner and are not as efficacious in building security as their widespread use would suggest. By blending community leaders’ voices and academic knowledge, we can craft a new, bold antiracist language for depolicing mental health.

Conclusion

Although gun violence afflicts America, inserting police into health care operations to promote safety is steeped in White supremacy and bias.35 Perhaps more than any other clinical setting, CMHCs serve marginalized populations plagued by racial, gun, and police violence. Healing societal damage caused by multigenerational systemic bias demands that we expand mental health care access and outreach rather than discriminate against those we serve. CMHCs must therefore be at the forefront of depolicing medicine by developing a new body of trauma-informed, culturally responsible, and historically corrective literature and policies.

References

- Paul DW Jr, Knight KR, Campbell A, Aronson L. Beyond a moment—reckoning with our history and embracing antiracism in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1404-1406.

-

American Psychiatric Association and National Medical Association jointly condemn systemic racism in America. News release. American Psychiatric Association; June 16, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/american-psychiatric-association-and-national-medical-association-jointly-condemn-systemic-racism-in-america

- McLeod MN, Heller D, Manze MG, Echeverria SE. Police interactions and the mental health of Black Americans: a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(1):10-27.

-

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2018 Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2019. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NMHSS-2018.pdf

- Lamb RH, Weinberger LE, DeCuir WJ. The police and mental health. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;53(10):1266-1271.

-

Fuller DA, Lamb HR, Biasotti M, Snook J. Overlooked in the undocumented: the role of mental illness in fatal law enforcement encounters. Treatment Advocacy Center; 2015. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/overlooked-in-the-undercounted.pdf

- Livingston JD. Contact between police and people with mental disorders: a review of rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(8):850-857.

- Lowe SR, Galea S. The mental health consequences of mass shootings. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2017;18(1):62-82.

-

Havaei F. Does the type of exposure to workplace violence matter to nurses’ mental health? Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(1):41.

- Kelen GD, Catlett CL. Violence in the health care setting. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2530-2531.

- Kelen GD, Catlett CL, Kubit JG, Hsieh YH. Hospital-based shootings in the United States: 2000 to 2011. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):790-798.e1.

-

Janofsky JS, Alampay M, Bonnie R, et al; Council on Psychiatry and Law. Position statement on weapons use in hospitals and patient safety. American Psychiatric Association; 2018. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/About-APA/Organization-Documents-Policies/Policies/Position-2018-Weapons-Use-in-Hospitals-and-Patient-Safety.pdf

- Wen H, Wilk AS, Druss BG, Cummings JR. Medicaid acceptance by psychiatrists before and after Medicaid expansion. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):981-983.

- Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176-181.

- Hammonds EM, Reverby SM. Toward a historically informed analysis of racial health disparities since 1619. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1348-1349.

-

Artiga S, Stephens J, Damico A. The impact of the coverage gap in states not expanding Medicaid by race and ethnicity. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2015. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-the-impact-of-the-coverage-gap-in-states-not-expanding-medicaid-by-race-and-ethnicity

-

Serious mental illness among adults below the poverty line. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. November 15, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2720/Spotlight-2720.html

- Ellis GL, Dehart DA, Black C, Gula MJ, Owens A. ED security: a national telephone survey. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12(2):155-159.

- Schoenfisch AL, Pompeii LA. Security personnel practices and policies in US hospitals: findings from a national survey. Workplace Health Saf. 2016;64(11):531-542.

-

Lett LA, Murdock HM, Orji WU, Aysola J, Sebro R. Trends in racial/ethnic representation among US medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1910490.

- Smalley CM, O’Neil M, Engineer RS, Simon EL, Snow GM, Podolsky SR. Dangerous weapons confiscated after implementation of routine screening across a healthcare system. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1505-1507.

- Metzl JM, Piemonte J, McKay T. Mental illness, mass shootings, and the future of psychiatric research into American gun violence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2021;29(1):81-89.

- Lamb HR, Weinberger LE. Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(4):483-492.

- Gao YN. Relationship between psychiatric inpatient beds and jail populations in the United States. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):33-42.

- Donnelly EA, Wagner J, Stenger M, Cortina HG, O’Connell DJ, Anderson TL. Opioids, race, and drug enforcement: exploring local relationships between neighborhood context and Black–White opioid-related possession arrests. Crim Justice Policy Rev. 2020;32(3):219-244.

-

Hinton E, Henderson L, Reed C. An unjust burden: the disparate treatment of Black Americans in the criminal justice system. Vera Institute of Justice; 2018. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/for-the-record-unjust-burden-racial-disparities.pdf

- Rankins RC, Hendey GW. Effect of a security system on violent incidents and hidden weapons in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):676-679.

-

Pompeii L, Benavides E, Pop O, et al. Workplace violence in outpatient physician clinics: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6587.

- Parker CB, Calhoun A, Wong AH, Davidson L, Dike C. A call for behavioral emergency response teams in inpatient hospital settings. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(11):E956-E964.

-

Alang S, McAlpine D, McClain M, Hardeman R. Police brutality, medical mistrust and unmet need for medical care. Prev Med Rep. 2021;22:101361.

- Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet. 2018;392(10144):302-310.

-

Alonso-Zaldivar R. Feds fund mental health crisis teams to stand in for police. ABC News. April 23, 2021. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/wireStory/feds-fund-mental-health-crisis-teams-stand-police-77269775

-

Climer BA, Gicker B. CAHOOTS: a model for prehospital mental health crisis intervention. Psychiatr Times. 2021;38(1):15. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/cahoots-model-prehospital-mental-health-crisis-intervention

-

Hailu R. A reckoning for health care professionals: should they be activists, too? Stat News. June 16, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://www.statnews.com/2020/06/16/doctors-protesting-racial-injustice

- Boyd RW. Police violence and the built harm of structural racism. Lancet. 2018;392(10144):258-259.