Abstract

Metropolitan Community College, a comprehensive multicampus academic institution in Omaha, Nebraska, installed portraits by the third author (MG) in the Health Careers Building and integrated them into an associate degree nursing curriculum. One goal was to expose nursing students to patients’ stories in ways that encourage them to look beyond pain rating scales and protocols to the many dimensions of patients as human beings. Using portraiture in this way could be applied to any health professions curriculum, as the intersections of humanities and health care prompted students and clinicians to look beyond science and into the emotional journeys of caring.

Portraiture in Nursing Curricula

In an effort to integrate portraiture into a nursing curriculum, Metropolitan Community College’s Department of Nursing exhibited Experience of Portraiture in a Clinical Setting (EPICS). This collection of portraits by the third author (MG), an artist-researcher, resulted from his arts-based research with patients experiencing head and neck cancers. Patients participated in the portraiture process as part of their cancer clinic visits.1

Students in an associate degree nursing program were exposed to EPICS’ 24 drawings and paintings depicting 5 patients with head and neck cancers. In September 2017, the college hosted a formal public exhibition of EPICS and a discussion with Gilbert and his fellow researchers, health care professionals, and 4 of the 5 study participants who sat for their portraits. Gilbert and one EPICS study participant also delivered guest lectures in nursing classes about portraiture and EPICS, engaging students in classroom discussions about health, illness, and the nature of interactions among art, artists, and patients during portraiture sessions. A survey was conducted to examine nursing students’ responses to being exposed to the patients’ portraits. This article examines how integrating portraiture into nursing education can offer an opportunity for nursing educators and students to reflect on patients’ and caregivers’ holistic human experience. Below, we share educators’ reflections on exhibiting EPICS in a college department of nursing, along with qualitative and quantitative analyses of students’ perceptions of the educational experience.

What Students Reported

A total of 123 individuals, mostly nursing students, completed the survey after viewing the portraits. Respondents reported contemplating a range of caring traits. After observing the EPICS exhibition, attendees reported observing the following emotions in the portraits: fear, vulnerability, uncertainty, sadness, acceptance, comfort, resilience, strength, courage, hope, empathy and compassion. Respondents were presented with a list of potential responses to the portraits, and a majority reported that they agreed or strongly agreed that, when looking at the portraits, they developed a sense of compassion and empathy (93.4%), understanding (91%), awareness (88.6%), acceptance (87.8%), gratitude (87.7%), resilience (84.4%), and ethics (79.5%). A majority of respondents also reported that, when viewing the portraits, they thought about how health and illness affect identity (92.6%), the impact of caregivers on patients (87.7%), the psychology of bodily illness or health (87%), visual qualities of health and illness (86.2%), and the impact of illness on caregivers (85.4%).

In the survey, respondents were asked to describe both their initial thoughts when they first entered the portrait exhibition and their concluding thoughts when leaving. Some reported that they initially questioned the reasons for including portraiture in nursing education and wondered, “How do portraits relate to medicine?” However, in describing their thoughts after attending the exhibition, many noted the value of making human connections with patients and reported recognizing the uniqueness of patients’ stories, listening to and reflecting on patients’ stories, and embracing curiosity or avoiding assumptions about patients. Ultimately, participants reported that this exhibit opened their eyes, inspired a desire to learn more about cancer, strengthened their desire and need to help others, and reaffirmed why they were pursuing a nursing career. In response to the survey question, “What is the most important message you are taking away from this exhibition?,” participants recognized that humanity is key; art can be healing; medicine is an art; healing is a process; and there are different ways of healing.

Value of Portraiture

Exposure to portraiture can offer an opportunity for caregivers to reflect on personal experiences that have drawn them into a profession of caring and compassion and serve as a tangible way of acknowledging the lived experiences of patients. The second author (LS) reflected:

As I sat with my dying mother, a multitude of moments were instilled as mental portraitures in my mind, such as when my son stood still at her bedside with his 7-year-old eyes filled with not knowing that would be the last time he would be with her, my father relentlessly trying to get my mom to take a bite of the pureed beets as a desperate attempt to deny the dying process, the hospice nurse playing the health care worker’s role that is normally my job, standing at the foot of the bed with the look that told us what we didn’t want to acknowledge and my eyes focused on the desk that my mother so recently sat [at] and struggled to write letters on as the brain tumor took over her ability to write…. The desk stared at us during those long days as we sat watching her slip away. This was a mental portrait in my mind … that desk has become a piece of the mental image of the experience as the grieving process continues.

Much like LS’s mother’s desk, images of the chair that participants sat in during the EPICS portraiture process (see Figure 1) became a means through which viewers engaged in deep reflection on the healing process. Physical objects can stimulate emotions that are felt during the portraiture experience and help construct meaning as the experiences are mentally processed and reflected upon. The same chair, which now sits in the office of the first author (SO)—the Dean’s Office at Metropolitan Community College—welcomes visitors as a continuation of the portraits now hung throughout the halls of the college. The ability to draw on one’s own lived experiences and emotions through portraiture is one way to integrate medicine and the humanities, as evidenced by viewers’ reactions to the portraits.

Figure 1. The Empty Chair, by Mark Gilbert

Courtesy of Mark Gilbert.

Media

Ink on paper.

The inaugural EPICS exhibit, which opened in 2017, provided the first public display of its 24 pictures and the first gathering of the participants who sat for those portraits, sans one, who had passed away. The event honored the participants in EPICS and gave the public its first opportunity to see the full collection of portraits. One family member was motivated to leave her residential care center for the first time since a catastrophic event had left her paralyzed.

“I know when I walk in the door in the morning and see Judy’s smile and her holding that cup, everything is going to be okay.”

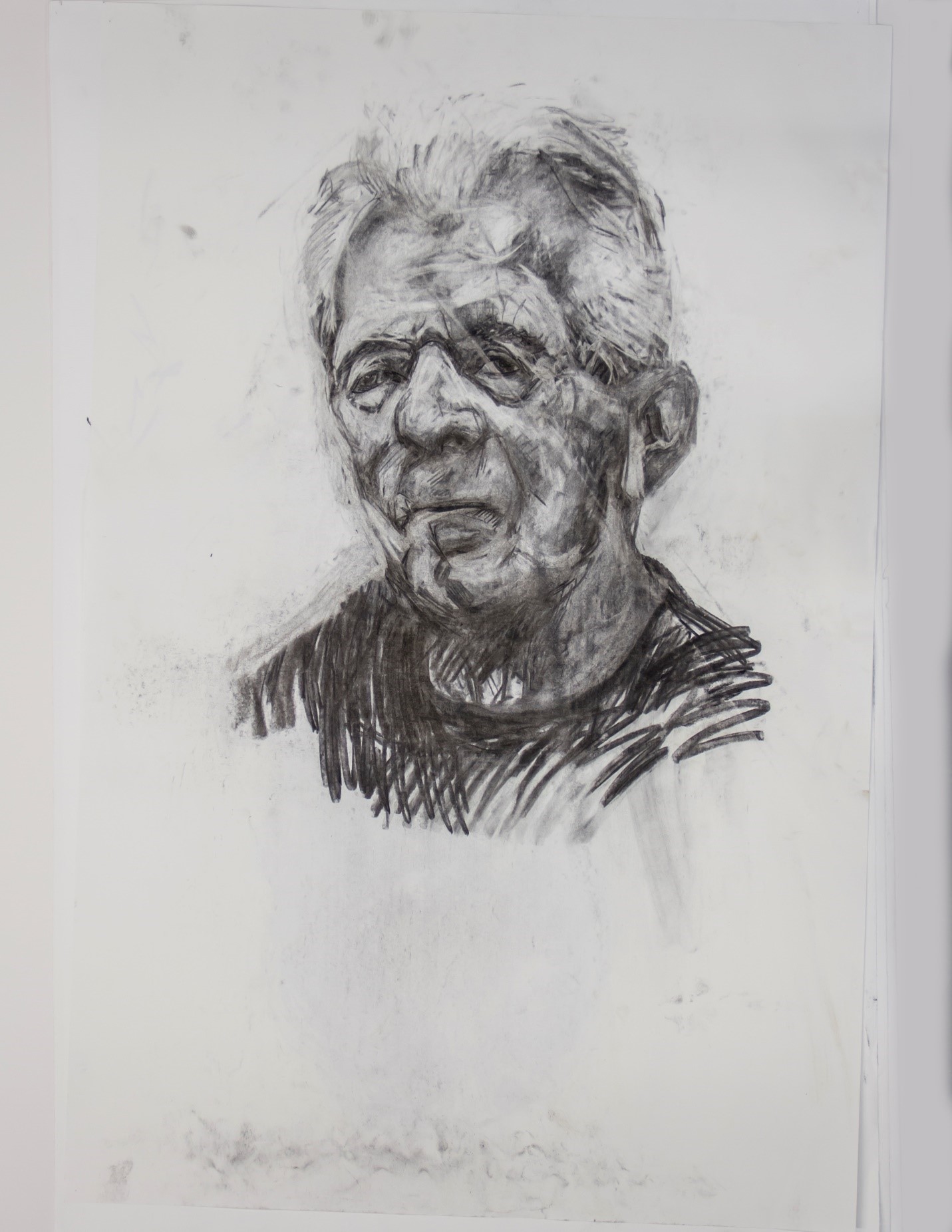

The extent to which lived experiences of engagement with portraiture can affect one’s life is often unexpected when the journey first begins. In particular, bringing together these individuals and their families led to unexpected connections. Marketing for the event led members of one family to find the portrait of their deceased loved one that they knew had been created but had since lost track of; that family came to the event and saw that portrait with great appreciation. Perhaps the most profound experience was the instant familiarity the participants had with each other. They had never met, but they felt a strong sense of fellowship through viewing each other’s portraits during the study. One of the EPICS sitters, John (see Figure 2), said to another EPICS sitter whom he had not met in person before the exhibit opening, “I feel like I already know you because I saw your portrait and felt your story every day as I was being drawn. It helped me get through the rough times.”

Figure 2. John, by Mark Gilbert

Courtesy of Mark Gilbert.

Media

Charcoal on paper.

Integrating EPICS Into the Curriculum

Integrating EPICS into the nursing curriculum at Metropolitan Community College has had unintentional effects, manifest in the reactions of both students outside nursing and staff to the portraits hung in the hallways. Prior to the titles and narratives associated with the EPICS collection being displayed, students routinely stopped and stared at the portraits, attempting to surmise the importance of these particular individuals. Although they had no concrete facts, they continued to visit, pause, and analyze the portraits. Students shared that they thought these portraits must be of important people, possibly large financial donors to the college or historians.

Slowly, the institution began to display pieces of information about the collection in a deliberate attempt to draw students into seeing the faces in the portraits: first, a patient’s name; second, the artist’s name; lastly, the story of the collection of EPICS. After the final piece of the narrative had been revealed, one would assume that the students and staff would be satisfied that they had found the answer to the mystery of the people in the portraits and grow tired of stopping to see them. Yet, what we found was an increase in visits to the portraits by the same students and staff. Students shared that they experienced a sense of peace and comfort in seeing the faces in EPICS each day. One student said, “It was like seeing a friend.” One staff member stated, “I know when I walk in the door in the morning and see Judy’s smile and her holding that cup, everything is going to be okay” (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Judy

Courtesy of Mark Gilbert.

Media

Pastel on paper.

Listening to the artist and the study participants in the panel describe the impact of the portraiture experience on their own lives, members of the audience were moved to reflect on their own experiences and internal images of previous lived experiences that were “portraits” in their own mind. We believe reflection on these lived experiences, in conjunction with portraiture in nursing education, can enhance soft skills and the development of empathic nursing care.

Future Directions

To our knowledge, there has been no other comparable pedagogical experience offered in nursing curricula. Moreover, to our knowledge, there are no other existing studies of exposure to portraiture in nursing education with an accompanying quantitative analysis of students’ perceptions of the educational experience. Nevertheless, our research is only suggestive.

Future research could fruitfully examine the impact of educators’ personal encounters with health alterations on their teaching practices—specifically, on their training nurses to perceive the patient as a holistic being with depth rather than simply as an individual with a health ailment. Through the journey of portraiture, faculty members have the opportunity to share their own lived experiences of transitioning from a caregiver to a care receiver or a patient’s family member. Furthermore, the portraits create opportunities for students to reflect on the fluidity of these roles and how their actions in caring for others become the very portraits we draw inspiration from. We believe that it is through these shared stories that students, as future health care professionals, become aware of the impact they have on their patients’ lived experience.

In contrast to other more affordable and accessible types of art, such as poetry and literature, there are barriers to integrating original paintings into nursing curricula—namely, the cost, transportation, and care of originals.2 These barriers often prevent the realization of the opportunity that we had here at Metropolitan Community College. We believe any exposure to MG’s work, whether viewed online or in person, is valuable for student learning and fosters caring when combined with the artist’s and patients’ narratives of the experience of portraiture. We remain committed to exposing students to original works of art and portraits of real patients.

Nonetheless, future research is needed to support the claim that original works of art and portraits of real patients are irreplaceable resources. We suspect that the specific nature of the paintings of real patients and the educational lecture and class discussions were important factors in students’ empathy-enhancing experience. Empirical support for this claim could aid in securing funding for institutions to integrate original works of art into curricula and to personally work with the artist, as was done at Metropolitan Community College.

References

- Gilbert MA, Lydiatt WM, Aita VA, Robbins RE, McNeilly DP, Desmarais MM. Portrait of a process: arts-based research in a head and neck cancer clinic. Med Humanit. 2016;42(1):57-62.

- Bruderle E, Valiga T. The arts and humanities: a creative approach to developing nurse leaders. Holistic Nurs Pract. 1994;9(1):68-74.