Abstract

One expression of structural injustice in the United States is delivery of health care according to patients’ race and insurance status. This de facto segregation in academic health centers limits community organizations’ and leaders’ capacity to dismantle racism and undermines health equity. This commentary on a case considers this problem, argues why academic health centers are ethically obliged to respond, and offers strategies to do so.

Case

PR is a community organizer who lives in a historically Black neighborhood in a large city near a prominent academic health center (AHC). Despite PR’s community’s proximity to this AHC, PR and other community members do not seek care there if they can avoid doing so, since they do not generally feel it is “meant for us.” PR and others in the community know that world-class clinicians practice at this AHC and that wealthy people from all over the world come to see them. Neither PR nor PR’s neighbors have ever seen a physician in this AHC, but they have received care at the AHC’s clinics that are staffed by trainees and students who are “volunteering” and doing “service learning.”

When PR and other local community leaders were invited to participate in a symposium hosted by the AHC, many referred to their health and health care experiences as segregated, or “2-tiered,” and felt condescended to by office staff and clinicians who knew they were insured by Medicaid. In the wake of social, cultural, and institutional responses not only to inequity laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, but also to anti-Black racism and state-sanctioned violence, the AHC is trying to learn how to respond more justly to health needs of its community members.

The AHC considers how to redesign and desegregate its health professions education structures to motivate health equity in communities in which the center and its clinics reside.

Commentary

Racism in American health care is no secret.1,2,3,4 As evidence of its scope continues to mount, many institutions have announced efforts to reduce racial disparities.5,6,7,8 With their supply of skilled clinicians, researchers, and financial resources, AHCs might appear well positioned to make—and perhaps even lead—this change. Their seeming abundance of resources, however, is inextricable from academic medicine’s long history of racism,9 experimentation on and abuse of Black bodies,10 and normalization of whiteness at the top of its hierarchy.11 Even the AHCs most committed to racial justice and equity will find it challenging, if not impossible, to simultaneously function within and transform American health care.

We have collectively spent the last decade working to understand and dismantle segregated health care in New York City. Over this time period, we have become increasingly convinced of the need to look beyond the walls of academic medicine for leadership in this effort. The better we understand our health care system, the clearer it becomes, in Audre Lorde’s words, that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”12

Still Segregated

Central to understanding our health care system is the realization that there is no one health care system. Despite the legal victories of the 1960s—and, in particular, the Social Security Amendments of 1965 outlawing de jure hospital segregation by race13—American health care remains segregated. Poor communities and communities of color are provided access to a different health care system than that accessed by more affluent, White communities. To take a few examples, Black and Hispanic women with very preterm births are more likely than White women to deliver at New York City hospitals with the highest rates of neonatal morbidity and mortality2; Black patients on Medicare who are treated for heart attacks tend to receive care at lower-performing hospitals than White patients on Medicare, even when they live in the same zip code14; and, in New York City during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, less-resourced intensive care units had higher COVID mortality rates than flagship hospitals.15 Unfortunately, this system of segregated care represents the status quo. Its ubiquity, however, should not justify its continued existence. A profession with a primary maxim to “do no harm”16 should not be content with a system that has been shown to disproportionately harm people of color.17

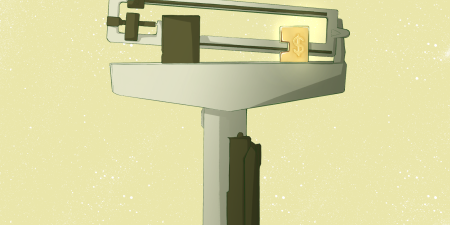

The reasons for such segregation are complex and multifactorial, but it is clear that health care financing and insurance coverage play an important role. Even after the passage of the Affordable Care Act of 2010,18 Black and Hispanic nonelderly adults are more likely to be uninsured19 or publicly insured with Medicaid20 and less likely to have employer-sponsored coverage than White nonelderly adults.21 Because Medicaid pays relatively less for services than private insurers, hospitals are incentivized to prioritize the care of patients with comparatively generous private insurance,22,23,24 limiting people of color’s access to top-performing hospitals, many of which are AHCs. Indeed, a recent investigation by the Lown Institute found that many of the most prestigious AHCs—Mayo Clinic Hospital Rochester, Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, NYU Langone Hospitals, and Massachusetts General Hospital, for example—are among the least equitable hospitals in their communities in terms of patient inclusivity, among other metrics.25,26 As a result, safety-net hospitals—those with explicit missions to serve the uninsured and underinsured—must care for those who are left behind. These safety-net institutions treat a concentrated pool of uninsured and underinsured patients, further widening the equity gap between them and the top-performing, revenue-generating hospitals.

Of course, insurance status and reimbursement rates do not entirely explain our segregated health care system. Geographic segregation, often created and enforced through measures such as redlining,27 is also a contributing factor, as evidenced by women often delivering at the hospital closest to their home irrespective of the quality of care provided.28 Unfortunately, the inequities created by geographic segregation are often deepened by health care resource allocation.29,30 In New York City, for example, many smaller community hospitals have closed or drastically reduced their services in recent years, shunting patients to the publicly funded NYC Health + Hospitals system.31 Many of these changes result from mergers with large AHCs. For example, in recent years Mount Sinai Health System drastically cut the services of Beth Israel Hospital32; Montefiore Medical Center planned to close Mount Vernon hospital33; and New York Presbyterian Hospital has sought to replace a needed inpatient psychiatric center at Inwood’s Allen Hospital with a more lucrative expansion of an orthopedic spine center.34,35 Notably, 18 hospitals have closed in New York City alone since 2003.36 This maneuvering has reduced services for many communities of color, increased patient volumes for remaining community hospitals, and concentrated services at wealthy AHCs.31 For every one thousand residents, Queens now has 1.5 hospital beds; Manhattan has 6.4.31

Segregated care can also be seen within the walls of AHCs. Frequently, AHCs have separate faculty or attending physician clinics for patients with private insurance, resident-run clinics for those on Medicaid, and sometimes student clinics for the uninsured.37,38,39,40 Ostrer et al showed that resident-run clinics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai had longer wait times and less availability than their counterpart faculty clinics.41 Another study found that patients treated by residents at one Boston AHC network were less likely to be up-to-date on chronic disease and cancer screenings.42

Solutions

Considering the many ways that AHCs are complicit in and benefit from segregated health care, those intent on making change should look outside of hospitals and clinics to learn from and follow the lead of organizers within the communities they serve. Historical examples of efforts to dismantle medical racism include the Black Panther Party’s medical clinics and the Young Lords’ occupation of Lincoln Hospital.43,44 The Black Panthers believed that lack of adequate housing, food, and health care were forms of violence, and they sought to provide solutions that were not forthcoming from government and hospitals. Their Ten Point Program called for free health care for Black and all oppressed people, and they implemented clinics and programs that were rooted in their communities.43 In 1970, the Young Lords occupied Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx, New York, in response to deplorable conditions faced by Puerto Ricans and Black Americans in the community and within the hospital.44 Recognizing where medicine fell short, the Young Lords also protested poor sanitation services, initiated community breakfast programs for poor children, and lead tuberculosis screening in East Harlem.45 The activism of the Young Lords and Black Panthers proved influential in the creation of the Patient Bill of Rights, expansion of community health clinics, screening for sickle cell anemia, and the federal school breakfast program, among other policies and legislation.45,46 To this day, their activism continues to influence how health care disparities are understood and reduced.47

AHCs can include community members and leaders on their admission panels to recruit diverse students from communities they seek to serve.

Such historical examples of efforts to dismantle racism in health care have modern-day counterparts. In Red Hook, a Brooklyn neighborhood still without its replacement inpatient facility after the 2013 closing of Long Island Hospital,48 the Red Hook Initiative49 and partners created a community-based screening tool to identify the medically fragile (eg, seniors and those with chronic medical conditions, especially the underserved or underinsured) during the Covid-19 pandemic. The Kings Against Violence Initiative50 in Brooklyn, a violence intervention program that relies on community experts to bridge the gap between a hospital and a community where interpersonal violence is a public health risk, trains hospital staff in trauma-informed care and provides referrals and follow-up services for victims of violence. And, in 2018, medical students at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons joined community activists to protest the aforementioned closure of the Allen Hospital Psychiatric Unit.35

Other health care desegregation efforts have broader goals. Medical students, residents, and physicians are collectively organizing alongside community members to demand racial equity and justice within AHCs as part of organizations such as the NYC Coalition to Dismantle Racism in the Health System.51 And broader movements, such as the Campaign for New York Health, which is fighting for statewide single payer care,52 and the Coverage4All campaign,53 which is working for health coverage for undocumented people,54 have leveraged community involvement to push for a more inclusive and equitable health care system. Nationally, the Poor People’s Campaign builds on Martin Luther King’s movement of the late 1960s by adopting equitable, universal health care as one of its key policy principles.55 In all of these examples, energy and ideas for reducing segregated care and racism in health care are coming from outside the power structure of AHCs.

Such outside leadership is important, and not only because communities closest to the problems have the deepest understanding of possible solutions. With community leadership there can be flexibility and creativity to reach beyond the standard academic tools of research to the tools of organizing and activism, such as demonstrations and direct action. Community leadership also has the ability to focus solely on the goal of change without the limitations encountered by AHCs and those within them, such as the pressure to publish in academic journals, whose research may fail to benefit the target commumnities,56,57 or the financial constraints enforced by the current system of financing and delivering health care in the United States.

Most importantly, however, is the community’s ability and commitment to fight for reforms that match the scale of the problems. Eliminating segregated care will require bold and systemic changes that address both the historical legacies of racism and the current financial structures that entrench it. Solutions proposed by AHCs, however, focus mainly on the former. For example, the Commonwealth Fund highlighted that AHCs’ strategies to address racism in health care include important goals, such as auditing school curricula for false claims about race, reviewing race-based algorithms, tracking health outcomes by race, creating reporting mechanisms for racist behavior, investing in training pipelines for students of color, and reexamining institutional policies through an equity lens.7 Although important, these strategies will not meaningfully address the fact that minority, uninsured, and Medicaid patients are underrepresented in New York City AHCs58 or change the fact that, nationwide, patients with Medicaid have reduced access to medical care.59 Addressing inequity will require AHCs to make financial decisions that seem unlikely without broader policy change, including change to how health care is paid for in the United States.

Roles for Academia

Despite the limits on what can be accomplished by AHCs, there are still opportunities for these organizations and those affiliated with them to create a less racist and segregated health care system. In addition to previously mentioned efforts that are largely based within the walls of institutions, AHCs can do more to center community perspectives, energy, and wisdom through reforms to two of their core historical legacies: education and research.

For example, AHCs’ selection and training of future health care workers can center community needs and public health by including community leaders. Specifically, AHCs can include community members and leaders on their admission panels to recruit diverse students who come from the communities they seek to serve. In addition, students and trainees can be taught—by compensated community leaders—about the ways in which medical racism impacts the community around them and how their AHC contributes to such problems. Students should also be educated in ethical concepts such as dual loyalty, with an explicit focus on the conflicts caused by loyalty to the success of the AHC within a segregated health care system.

With regard to research, AHCs can follow the well-established principles of participatory-based community research that center equitable partnerships with community collaborators and the dissemination of results to affect change.60 Even if publishing takes longer, AHCs can challenge themselves, their researchers, and their students to conduct research that engages the community and is solutions oriented. Institutional review boards and community advisory boards will continue to be important partners in these efforts.

AHCs can also encourage students to use the time they would typically dedicate to academic research to working with community organizations and participating in community movements, even if doing so does not result in standard research products. To be successful, these efforts would need to be matched by commitments from residency programs and other employers to value such efforts in their selection processes. Commitments to community activism and justice work could even be considered in faculty promotions and leadership roles.

Thus, there is an important role for AHCs to play in training health care clinicians and designing systems that will promote equitable health care. However, even with socially just education and research methods, AHCs would still contribute to segregated care as participants in a system that incentivizes it.

Looking Ahead

Dismantling racism in medicine will require transforming the health care system as we know it. Rather than leading this charge, academic medicine should recognize its own limitations as part of the system and seek to play a supportive role. Considering medicine’s long history of arrogance and paternalism, adopting such a humble position will be challenging. Ultimately, however, continued reliance on traditional tools of academic medicine to dismantle systems of oppression would lead only to their evolution, not their demise.

References

-

Eberly LA, Richterman A, Beckett AG, et al. Identification of racial inequities in access to specialized inpatient heart failure care at an academic medical center. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12(11):e006214.

- Howell EA, Janevic T, Hebert PL, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J. Differences in morbidity and mortality rates in Black, White, and Hispanic very preterm infants among New York City hospitals. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(3):269-277.

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(16):4296-4301.

- Ray KN, Chari AV, Engberg J, Bertolet M, Mehrotra A. Disparities in time spent seeking medical care in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1983-1986.

-

Addressing racism: a road map for action. Mount Sinai. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.mountsinai.org/about/addressing-racism

-

Mass general’s plan to address structural equity. Massachusetts General Hospital. November 16, 2020. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.massgeneral.org/news/article/plan-to-address-structural-equity

-

Hostetter M, Klein S. Confronting racism in health care: moving from proclamations to new practices. Commonwealth Fund. October 18, 2021. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/oct/confronting-racism-health-care

-

Olayiwola JN, Joseph JJ, Glover AR, Paz HL, Gray DM II. Making anti-racism a core value in academic medicine. Health Affairs Forefront. August 25, 2020. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200820.931674/full/

- Steinecke A, Terrell C. Progress for whose future? The impact of the Flexner Report on medical education for racial and ethnic minority physicians in the United States. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):236-245.

-

Washington HA. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Doubleday; 2006.

-

Livingston S. Racism still a problem in healthcare’s C-suite. Modern Healthcare. February 23, 2018. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180224/NEWS/180229948/racism-still-a-problem-in-healthcare-s-c-suite

-

Lorde A. The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. In: Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press; 2007:110-114.

-

Social Security Amendments of 1965, Pub Law No 89-97, 79 Stat 286 (1965).

-

Chandra A, Kakani P, Sacarny A. Hospital allocation and racial disparities in health care. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 28018. October 2020. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28018/w28018.pdf

-

Rosenthal BM, Goldstein J, Otterman S, Fink S. Why surviving covid might come down to which NYC hospital admits you. New York Times. July 1, 2020. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/01/nyregion/Coronavirus-hospitals.html

-

Hippocratic Oath. National Library of Medicine. Updated February 7, 2012. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath.html

-

Asch DA, Islam MN, Sheils NE, et al. Patient and hospital factors associated with differences in mortality rates among Black and White US Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112842.

-

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub L No 11-148, 124 Stat 119 (2010).

-

Uninsured rates for the nonelderly by race/ethnicity: 2019. Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/state-indicator/nonelderly-uninsured-rate-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

-

Medicaid coverage rates for the nonelderly by race/ethnicity: 2019. Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/nonelderly-medicaid-rate-by-raceethnicity/

-

Straw T. Trapped by the firewall: policy changes are needed to improve health coverage for low-income workers. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2019. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/trapped-by-the-firewall-policy-changes-are-needed-to-improve-health-coverage-for

-

Fact sheet: underpayment by Medicare and Medicaid. American Hospital Association. February 2022. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.aha.org/fact-sheets/2020-01-07-fact-sheet-underpayment-medicare-and-medicaid

-

Glastris P, Longman P. Perspective: American hospitals are still segregated. That’s killing people of color. Washington Post. August 4, 2020. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/08/05/segregated-hospitals-killing-people/

-

Cunningham P, Rudowitz R, Young K, Garfield R, Foutz J. Understanding Medicaid hospital payments and the impact of recent policy changes. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 9, 2016. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.kff.org/report-section/understanding-medicaid-hospital-payments-and-the-impact-of-recent-policy-changes-issue-brief/

-

Garber J. America’s “best” hospitals still underperform on equity. Lown Institute. July 27, 2022. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://lowninstitute.org/americas-best-hospitals-still-underperform-on-equity/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=americas-best-hospitals-still-underperform-on-equity

-

Saini V, Brownlee S, Gopinath V, Smith P, Chalmers K, Garber J. 2022 methodology of the Lown Institute Hospitals Index for social responsibility. Lown Institute; 2022. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://lownhospitalsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2022_Lown_Index_Methodology.pdf

- Diaz A, O’Reggio R, Norman M, Thumma JR, Dimick JB, Ibrahim AM. Association of Historic Housing Policy, modern day neighborhood deprivation and outcomes after inpatient hospitalization. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):985-991.

- Phibbs CS, Lorch SA. Choice of hospital as a source of racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal mortality and morbidity rates. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;274172(3):221-223.

- Buchmueller TC, Jacobson M, Wold C. How far to the hospital? The effect of hospital closures on access to care. J Health Econ. 2006;25(4):740-761.

- Saghafian S, Song LD, Raja AS. Towards a more efficient healthcare system: opportunities and challenges caused by hospital closures amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Care Manage Sci. 2022;25(2):187-190.

-

Dunker A, Benjamin ER. How structural inequalities in New York’s health care system exacerbate health disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for equitable reform. Community Service Society. June 4, 2020. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://www.cssny.org/news/entry/structural-inequalities-in-new-yorks-health-care-system

-

Marsh J, Hogan B, Musumeci N. Mount Sinai Beth Israel relocation questioned by advocates. New York Post. December 13, 2019. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://nypost.com/2019/12/13/health-care-advocates-demand-answers-about-mount-sinai-beth-israel-relocation-plan/

-

Robinson D. Why Montefiore finances are key Mount Vernon Hospital closure detail. Lohud. January 16, 2020. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.lohud.com/story/news/health/2020/01/16/why-montefiore-finances-key-mount-vernon-hospital-closure-detail/4481264002/

-

LaMantia J. New York-Presbyterian to replace Inwood psych unit with outpatient services. Modern Healthcare. April 6, 2018. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180406/NEWS/180409929/new-york-presbyterian-to-replace-inwood-psych-unit-with-outpatient-services

-

Whitman E. A New York community fights to keep a psychiatric ward in its own backyard. Nation. October 2018. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/new-york-presbyterian-allen-hospital-psychiatric-ward/

-

Robinson D. Dozens of NY’s hospitals closed. Then COVID-19 hit. Now marginalized patients are dying. Here’s why. Lohud. April 10, 2020. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.lohud.com/story/news/coronavirus/2020/04/10/why-ny-hospital-closures-cutbacks-made-covid-19-pandemic-worse/5123619002/

-

Calman NS, Golub M, Ruddock C, Le L, Hauser D; Action Committee of the Bronx Health REACH Coalition. Separate and unequal care in New York City. J Health Care Law Policy. 2006;9(1):105-120.

- Charlson ME, Karnik J, Wong M, McCulloch CE, Hollenberg JP. Does experience matter? A comparison of the practice of attendings and residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):497-503.

- Scheid D, Logue E, Gilchrist VJ, et al. Do we practice what we preach? Comparing the patients of faculty and residents. Fam Med. 1995;27(8):519-524.

- Amat M, Glassman R, Basu N, et al. Defining the resident continuity clinic panel along patient outcomes: a health equity opportunity. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(9):2615-2621.

-

Ostrer L, Austin C, Okah E, Ahsan S. Intersections between the Movement for a National Health Program and the Fight for Racial Justice. Paper presented at: Annual Students for a National Health Program Summit; March 5, 2016; Nashville, TN. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://pnhp.org/slideshow/2016%20SNaHP%20Summit%20PPTs/Breakout%202_Intersections%20Between%20the%20Movement%20for%20a%20National%20Health%20Program%20and%20the%20Fight%20for%20Racial%20Justice.pptx

-

Essien UR, He W, Ray A, et al. Disparities in quality of primary care by resident and staff physicians: is there a conflict between training and equity? J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1184-1191.

- Bassett MT. Beyond berets: the Black Panthers as health activists. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1741-1743.

-

Francis-Snyder E. The hospital occupation that changed public health care. New York Times. October 12, 2021. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/12/opinion/young-lords-nyc-activism-takeover.html

-

Fernández J. The Young Lords: A Radical History. University of North Carolina Press; 2020.

- Frierson JC. The Black Panther Party and the fight for health equity. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(4):1520-1529.

-

Blackstock UA, Blackstock OJ. “Serving the people body and soul”—centering Black communities to achieve health justice. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(1):e201523.

-

Hartocollis A. The end for Long Island College Hospital. New York Times. May 23, 2014. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/23/nyregion/the-end-for-long-island-college-hospital.html

-

Red Hook Initiative. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://rhicenter.org/

-

Kings County Hospital-based violence intervention. Kings Against Violence Initiative. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://kavibrooklyn.org/ourwork/hospital

-

NYC Coalition to Dismantle Racism in the Health System. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://nyccoalitiontodismantleracism.wordpress.com

-

As pandemic rages, lawmakers reintroduce New York Health Act with majority support in state legislature. New York State Senator Gustavo Rivera. March 10, 2021. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.nysenate.gov/newsroom/articles/2021/gustavo-rivera/pandemic-rages-lawmakers-reintroduce-new-york-health-act

-

#Coverage4All. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://www.coverage4all.info

-

Awawdeh M, Maxwell J. Immigrant New Yorkers deserve an equal chance at economic recovery. Syracuse.com. March 2, 2021. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.syracuse.com/opinion/2021/03/immigrant-new-yorkers-deserve-an-equal-chance-at-economic-recovery-commentary.html

-

14 policy priorities to heal the nation: a moral and economic agenda for the first 100 days. Poor Peoples Campaign. December 1, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.poorpeoplescampaign.org/resource/policy-and-legislative-priorities/

- Guraya SY, Norman RI, Khoshhal KI, Guraya SS, Forgione A. Publish or perish mantra in the medical field: a systematic review of the reasons, consequences and remedies. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32(6):1562-1567.

-

McFarling UL. “Health equity tourists”: how white scholars are colonizing research on health disparities. STAT. September 23, 2021. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.statnews.com/2021/09/23/health-equity-tourists-white-scholars-colonizing-health-disparities-research/

- Tikkanen RS, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, et al. Hospital payer and racial/ethnic mix at private academic medical centers in Boston and New York City. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47(3):460-476.

-

Hsiang WR, Lukasiewicz A, Gentry M, et al. Medicaid patients have greater difficulty scheduling health care appointments compared with private insurance patients: a meta-analysis. Inquiry. 2019;56:46958019838118.

- Cacari-Stone L, Wallerstein N, Garcia AP, Minkler M. The promise of community-based participatory research for health equity: a conceptual model for bridging evidence with policy. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1615-1623.