Abstract

Artist Francisca Lita Sáez considers experience of physicians during Spain’s COVID-19 pandemic. Three acrylic and pastel paintings convey defenseless human beings’ confrontations with the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is not yet controlled, leaving suffering and death in its wake. A physician-artist collaboration offers a visual representation of the clinical and ethical magnitude of the pandemic and humanity’s fight for survival.

Views From Spain

Artist Francisca Lita Sáez and physician Teófila Vicente Herrero, like many of us, endured a long period of quarantine in Spain. Their collaboration informs art’s capacity to help us find our way when medicine is overwhelmed and when science and its resources are outmatched. The series COVID-19 includes 7 acrylic and pastel paintings, 3 of which are below. An image of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is represented in each; Lita Sáez’s characteristic uses of color and human and nonhuman animal (especially insect) anatomy invite a viewer to consider, perhaps, feelings of abandonment and defenselessness in our collective and individual struggles to survive.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus emerged in Wuhan, China and spread rapidly around the world. There is currently no available clinically approved antiviral drug or vaccine, so need for research and discovery is urgent.1 The World Health Organization has encouraged researchers and clinicians to think in innovative ways to reduce risk for individuals and mitigate spread in communities across the world.2 Art-based ways of thinking can motivate innovation and have, for example, long been used to help humanity make sense of illness and death experiences during bubonic plague or the 1918 (Spanish) flu outbreaks, which are referenced in the 3 paintings3,4,5,6 and have informed our understandings of and responses to disease.7 Lita Sáez’s paintings are situated in this tradition and have also served therapeutic purposes.

Vicarious Art Therapy

Art therapy draws on creation to facilitate psychological and emotional expression to complement verbal, linguistic expressions.8 The British Association of Art Therapists defines art therapy as “a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as its primary mode of expression and communication.”9 The American Art Therapy Association also defines art therapy as a valuable complement to clinical psychological approaches to psychotherapeutic healing.10 Lita Sáez’s paintings invite, perhaps, a viewer to contemplate communicating among our own and others’ experiences of the reality that humanity is not currently up to the fight against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The paintings propose the value of vicarious art therapy as a possible pandemic intervention.11,12,13,14

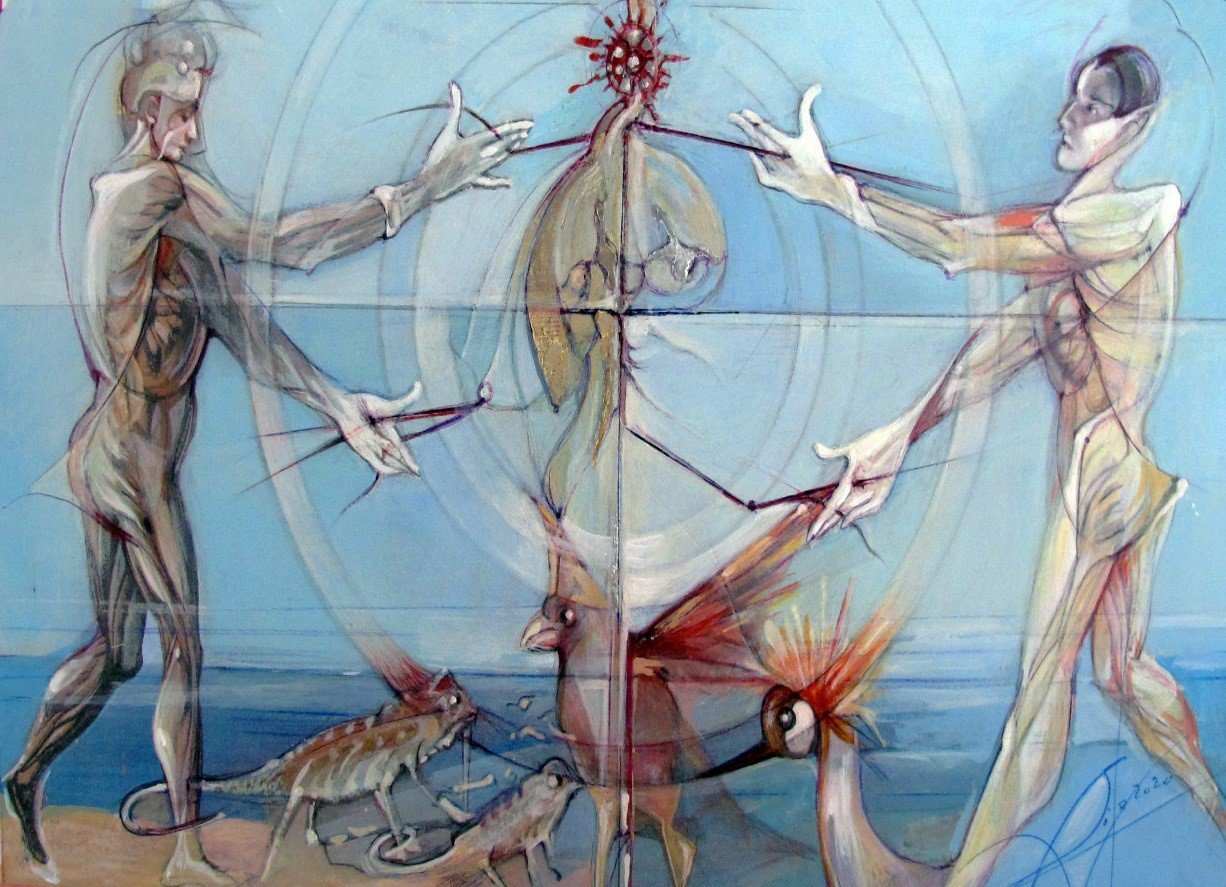

In The Threat, figures at right respond to attack by the SARS-CoV-2 virus at center. Like the Furies from Greco-Roman mythology—and like clinicians—these figures try to protect the cosmos from chaos and infection.

Figure 1. The Threat, 2020, by Francisca Lita Sáez

Media

Acrylic and pastels, 18" x 25".

In An Unequal Fight, 2 figures try to protect human and nonhuman organs from viral invasion. In both paintings, red suggests the novel virus’ malignancy, against which we have inadequate immunity.

Figure 2. An Unequal Fight, 2020, by Francisca Lita Sáez

Media

Acrylic and Pastels, 18" x 25".

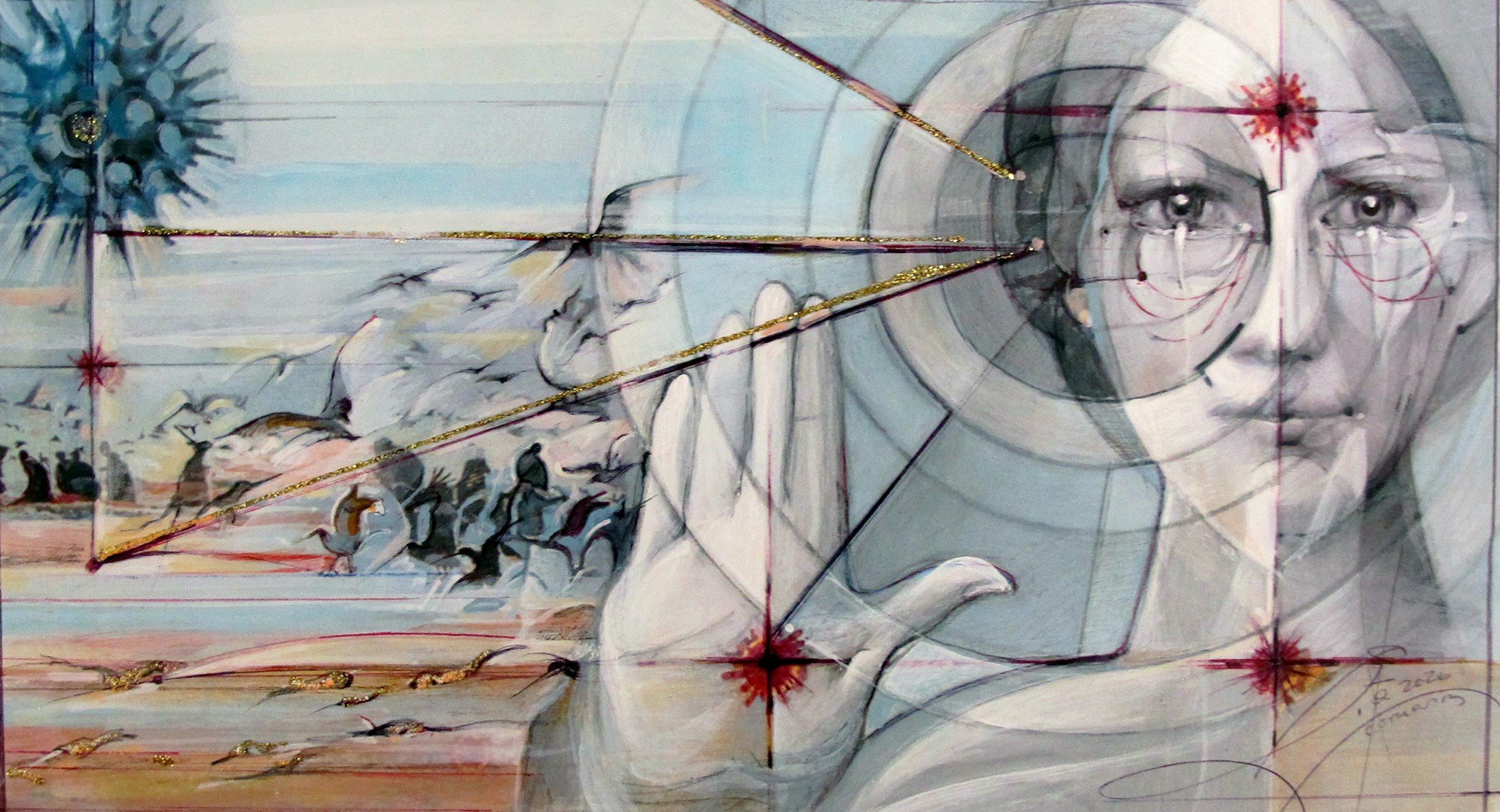

In Stop Pandemic, a well-defined individual suffers infection despite a hand raised in a plea to stop the virus’ blows, symbolized in red as direct hits. Other figures, less defined in shape and color, flee, suggesting capitulation to illness, despite our pleas and despite our fight.

Figure 3. Stop Pandemic, 2020, by Francisca Lita Sáez

Media

Acrylic and pastels, 18" x 25".

Lita Sáez’s paintings portray the SARS-CoV-2 virus’ global trail of death, but they suggest that hope might yet spring from collaboration between art and medicine and the therapeutic capacity of both.

References

-

Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91-98.

-

Redefining vulnerability in the era of COVID-19 [editorial]. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1089.

- Sweeney G. Salvation in a time of plague. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(5):E441-E445.

- Dequeker J. The plague and the art of painting: some examples. Verh K Acad Geneeskd Belg. 1999;61(2):411-416.

- Peiffer-Smadja N, Thomas M. The plague: a disease that is still haunting our collective memory. Rev Med Interne. 2017;38(6):402-406.

- Ziskind B, Halioua B. Histoire de la quarantaine. Rev Prat. 2008;58(20):2314-2317.

- Salter V, Ramachandran M. Medical conditions in works of art. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2008;69(2):91-94.

-

Vicente-Herrero T. Art and therapy in the Valencian context of the crisis, 2008-2018. In: De la Calle R, ed. Between Crisis, Resistance and Creativity: The Last Ten Years of Contemporary Valencian Art (2008-2018). España, Valencia: Polytechnic University of Valencia; 2020.

-

The British Association of Art Therapists. What is the art therapy? https://www.baat.org/About-Art-Therapy. Accessed July 9, 2020.

-

American Art Therapy Association. About art therapy. https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/. Accessed July 9, 2020.

-

Zucchella C, Sinforiani E, Tamburin S, et al. The multidisciplinary approach to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. A narrative review of non-pharmacological treatment. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1058.

-

Shaballout N, Aloumar A, Neubert TA, Dusch M, Beissner F. Digital pain drawings can improve doctors’ understanding of acute pain patients: survey and pain drawing analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(1):e11412.

- Rentz CA. Memories in the making: outcome-based evaluation of an art program for individuals with dementing illnesses. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2002;17(3):175-181.

-

Ruiz MI, Aceituno D, Rada G. Art therapy for schizophrenia? Medwave. 2017;17(suppl 1):e6845.