Abstract

What clinicians document about patients can have important consequences for those patients. Paternalistic language in patients’ health records is of specific ethical concern because it emphasizes clinicians’ power and patients’ vulnerabilities and can be demeaning and traumatizing. This article considers the importance of person-centered, trauma-informed language in clinical documentation and suggests strategies for teaching students and trainees documentation practices that express clinical neutrality and respect.

Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge.

Toni Morrison1

Introduction

It is the end of a long day, and you have just finished seeing a new patient for chronic lower back pain. In reviewing her records, you learn that she uses self-injury to manage overwhelming distress, has a history of childhood attachment trauma, and was previously diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, opioid use disorder, and chronic low back pain. It takes you 10 minutes to write the note, in which you are careful to provide the rationale for having lowered her pain medication and referred her to physical therapy. You feel the encounter went surprisingly well. She leaves seeming optimistic about the new plan, expressing that she didn’t realize physical therapy could be so effective. She liked how the plan centered around being more active, which aligned with her goal for weight loss. She remembered how she used to enjoy long treks throughout her neighborhood. It had been quite some time since she allowed herself to picture getting back out there.

Upon follow-up, the tension in the room is palpable. She seems cold and distant. You are genuinely concerned and ask her how she has been doing and if she has been able to go to physical therapy. At first, her voice is quivering, but it grows confident with anger as she describes having read your documentation in the patient portal. “I thought you got me,” she said. “Actually, I am glad the patient portal exists because now I can see, in black and white, exactly what my doctors really think of me. What does it even mean to have ‘failed’ prior medication trials and made ‘inconsistent attempts’ at lifestyle modification for morbid obesity? Are you kidding me? Who do you think you are? Oh, and also, I haven’t been ‘drug seeking’ for years. What I have been seeking is treatment! That’s it. I don’t need the extra judgment.”

Before you keep reading, take a moment to pause and see what occurs to you as you imagine the experience described above. Imagine reading a note alongside this patient during the next session. Are there thoughts about how this session might go or images or sensations that arise? Are you thinking about a particular patient you have worked with? Repeat the same exercise in your mind and switch your role: you are the patient in this situation. How might this experience affect you as a patient?

When you have completed the exercises, do what you need to do to refocus—perhaps by taking a few deep breaths or taking a short mindful break. Keep this exercise in mind as you continue reading.

Clinical Language

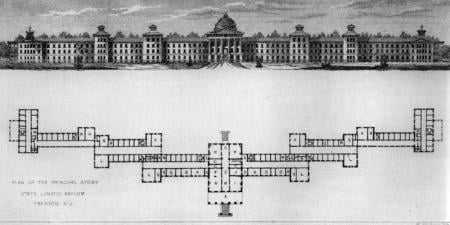

The language clinicians learn and adopt is powerfully shaped by the dominant culture: medical language was shaped by paternalism,2 and the remnants of this origin are still apparent today. Up until the mid-20th century, the paternalistic model of the patient-physician relationship3 dominated the medical field, including behavioral health. In this model, the clinician is viewed as an authority figure who has something the patient needs, and the patient is seen as a sufferer in need of the clinician’s expertise.3 Inherent in this model is an asymmetrical power dynamic in which the clinician can recreate the powerlessness a patient might have experienced when left with no autonomy or choice in a traumatic situation. For many people with marginalized identities, going to the doctor is already an anxiety-provoking and scary experience. One can imagine how the paternalistic model has the potential to further amplify the difficulty people might experience while seeking care, as an environment shaped by paternalism is not trauma informed and instead potentially retraumatizing.4,5

Even if unintentional, language reflecting the essence of paternalism leads to worse health care outcomes6 and is often perceived as demeaning, shaming, or blaming, and it risks being delivered in an authoritative and even condescending tone. Examples of normalized, though clearly problematic, terms commonly used in electronic health records (EHRs) include the following: noncompliant, drug seeker, manipulative, addict, morbidly obese, insane, hysterical, failed to…, claims to…, borderline tendencies, malingerer, frequent flier, and she’s a cutter. What does this language say about how the clinician views this person? What do these labels convey to other clinicians? How do they affect trainees who learn from these clinicians? How do they impact the culture of the clinical environment? How might the person feel when they read these terms describing themselves?

An environment shaped by paternalism is not trauma-informed and instead potentially retraumatizing.

With the passage of the 21st Century Cures Act,7 providers in EHR incentive programs nationwide must attest to “meaningful use” of EHRs to avoid a penalty. Clinicians must now take into consideration the impact of their language on the care they deliver. A shift in the culture of medicine toward recovery-oriented and trauma-informed care models has led clinicians to be more mindful of the impact of their words on others and, specifically, to use unbiased descriptions of people seeking services without discriminatory undertones. These models interrogate the power structures upheld by paternalism and require clinicians to acknowledge their responsibility in forming a collaborative environment that acknowledges the patient’s expertise and authority in their care.4

New Approaches to EHR Documentation

There are several frameworks that clinicians and educators can familiarize themselves with to improve EHR documentation and especially to teach a new way of approaching documentation. The Risking Connection framework8 emphasizes that any relationship aiming to be therapeutic is defined by the following components: respect, information, connection, and hope (RICH). The RICH model is described as follows: Respect is conveyed through sensitive use of language and respect for the patient’s views. Language that is respectful emphasizes abilities over limitations without a demeaning or shaming undertone and has the power to reduce stigma and discriminatory practices in medicine.9 Useful information is shared with patients to empower them with knowledge about their experience. Connection through empathic attunement is critical for healing and not just an afterthought. It requires sensitive responses, empathic understanding, and careful listening. Hope is communicated through actions, words, and body language and is ultimately fueled by capacity for compassion. The RICH model is inherently empowering, as persons accessing care play a central role in their treatment team, and all team members work collaboratively to help them achieve their goals.

For example, in the vignette, the note in the patient portal uses labels (eg, “failed,” “drug seeking”) and diagnoses (“lower back pain”) that emphasize pathology rather than focusing on resilience factors and explaining how and why the patient might have developed the behaviors and symptoms leading to the diagnosis. There is a key difference here between the approach taken in the vignette and the RICH model: the former emphasizes “what is wrong with the patient” and the latter “what went wrong to lead the patient to make those adaptations.” The former may lead to unintended patient blaming and labeling, which does not make for a therapeutic interaction or environment. For example, in the statement, the patient ‘‘‘failed’ prior medication trials and made ‘inconsistent attempts’ at lifestyle modification for morbid obesity,” the term failed implies that the patient is at fault. It would have been more respectful and information-focused to write in the note, “the medications tried were not helpful.” Moreover, the term inconsistent attempts does not explain what led the patient to act the way she did. It does not address possible difficulties she experienced in trying to change her lifestyle, such as lack of access to a gym, inability to afford specialty foods, or there being no grocery store with fresh produce near her home. Avoiding negative language and including possible explanations for her behavior in the note might have been received more positively by the patient.

Shifts in clinicians’ approaches to EHR documentation must go hand in hand with shifts in how they care for patients. Shaping a curriculum for medical students and residents requires thoughtful unlearning of the paternalistic model and joining with patients in their recovery. The National Harm Reduction Coalition published a fact sheet on undoing stigma and the importance of person-centered language in this process, emphasizing that “A person is a person first, and a behavior is something that can change—terms like ‘drug addict’ or ‘user’ imply someone is ‘something’ instead of someone. Stigma is a barrier to care, and we want people to feel comfortable when accessing services. People are more than their drug use and harm reduction focuses on the whole person.”10

Improving Curricula

A solution to problematic language in health record documentation cannot be a 1-hour “cultural competence” or “patient-centered language” didactic. For example, the Columbia University Public Psychiatry curriculum,11 with which all of the authors are currently or were previously associated, adopts recovery-oriented, systems-based practice and justice and trauma-informed frameworks in patient care that are woven throughout the entire curriculum. Understanding that trauma-informed care must avoid marginalization—including linguistic marginalization—because all marginalization is traumatizing, the Columbia University curriculum has also implemented an antiracist lens.

To apply these lenses, the Columbia University curriculum starts by having students step out of the medical model, which focuses on symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of disease. It then has them focus on Who is this person and how can I help them? This question completely reorients students from thinking, I am the doctor with the knowledge and will treat this illness to I am a trained professional who can collaborate with this person to try to get their needs met, which is a recovery-oriented, person-centered approach. The curriculum also requires trainees to understand the community and the medical and social structures that the person has to navigate to get their needs met, which describes the systems-based practice approach.12 (Teaching antiracism and social justice requires a safe and brave learning environment13 that allows trainees to have open discussions about the systematic marginalization of people who are “othered” in our society because race and ethnicity cannot be ignored in the way medicine is practiced.)

Implementation of the SMART Tool14 developed by the American Association for Community Psychiatry is one way to create a learning environment that honors patients. Another is through the co-creation of a curriculum with people with lived experience, or the Peer Advisor Program.15 This program includes experiential longitudinal learning through monthly meetings with a certified peer advocate throughout the training.16 This program also flips the hierarchy, as the person with lived experience serves as the advisor.17

While implementation of change in EHR documentation is a lengthy process, it is worthwhile, given the impact on outcomes and satisfaction such change could have on people who have access to their records.18 Medical schools and residency programs committed to equipping their trainees with the skills needed for inclusive and nonjudgmental documentation might consider consulting with trauma-informed care organizations for in-person training tailored to faculty and students. While didactics on therapeutic interactions and the impact of language on the therapeutic environment are imperative, they are rarely enough to affect meaningful change in practice.19 Faculty modeling for students healthy and respectful communication about patients when they are not present, as well as during rounds and all other clinical interactions, is critical if we hope to change the culture of medicine. Experiential learning, such as role-playing clinical interactions with certified peers or standardized patients, has been proven to have a lasting impact on trainees’ interactions with patients.20 A particularly engaging exercise used in training and workshop settings involves the rewriting of a typical note. Trainees are encouraged to critically examine their documentation and rewrite it in a patient-centered, trauma-informed, empowering tone.21 Once a critical mass of newly trained clinicians adopts these principles, they may influence the existing culture.

Conclusion

Going forward, it would be prudent for medical education to be informed by the 21st Century Cures Act and its ramifications. Training programs will need to make a cultural change to become more person centered and recovery oriented. To mitigate harm to patients, education for medical students and trainees will also need to modify didactics to include a focus on language used in notes and the message being conveyed, such that the audience for the note includes the subject of the note. This linguistic change would highlight that patients are now integral members of the clinical team.

References

-

Morrison T. Toni Morrison Nobel lecture. Nobel Prize. December 7, 1993. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1993/morrison/lecture/

-

Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. A Philosophical Basis of Medical Practice: Toward a Philosophy and Ethic of the Healing Professions. Oxford University Press; 1981.

- Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267(16):2221-2226.

-

Easterly W. The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor. Basic Books; 2013.

- Cassel CK. The patient’s role in decision-making. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1747-1754.

- Lipson SA, Hall JA, Schwartz JS. The impact of stigmatizing language in medical records on patients’ access to care and quality of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1246-1252.

-

21st Century Cures Act, Pub L No. 114-255, 130 Stat 1033 (2016).

-

Risking Connection® (RC) training. Traumatic Stress Institute. Accessed October 30, 2023. https://www.traumaticstressinstitute.org/risking-connection-training/

- Volkow ND, Gordon JA, Koob GF. Choosing appropriate language to reduce the stigma around mental illness and substance use disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(13):2230-2232.

-

Respect to connect: undoing stigma. National Harm Reduction Coalition. Updated February 2, 2021. Accessed June 2, 2023. https://harmreduction.org/issues/harm-reduction-basics/undoing-stigma-facts/

-

Curriculum—academic modules overview. Columbia University Department of Psychiatry. Accessed June 2, 2023. https://www.columbiapsychiatry.org/education-and-training/clinical-fellowships/public-psychiatry-fellowship/curriculum-academic-modules

- Ranz JM, Weinberg M, Arbuckle MR, et al. A four factor model of systems-based practices in psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(6):473-478.

-

Stubbs VD. The 6 pillars of a brave space. University of Maryland School of Social Work. Accessed October 30, 2023. https://www.ssw.umaryland.edu/media/ssw/field-education/2---The-6-Pillars-of-Brave-Space.pdf

-

SMART tool. American Association for Community Psychiatry. Accessed October 30, 2023. https://www.communitypsychiatry.org/keystone-programs/smart-tool

-

Kalocsai C, Agrawal S, de Bie L, et al. Power to the people? A co-produced critical review of service user involvement in mental health professions education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. Published online May 29, 2023.

-

Applicants. Columbia University Department of Psychiatry. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.columbiapsychiatry.org/education-and-training/clinical-fellowships/public-psychiatry-fellowship/applicants

-

Bodic MM, Munoz-Hilliard A, Agrawal S. Flipping the power dynamic and learning from people with lived experience: the peer advisor program model? Paper presented at: American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 20-24, 2023; San Francisco, CA.

-

Carini E, Villani L, Pezzullo AM, et al. The impact of digital patient portals on health outcomes, system efficiency, and patient attitudes: updated systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(9):e26189.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226-235.

- LeBlanc TW. Communication skills training in the twenty-first century. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(2):138-141.

-

Bodic MM, Salamanca LAF, Steen PS, Chong NA. Am I ready for my patients to see their records? A guide to clinicians on patient-centered recovery-oriented documentation. Paper presented at: American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 20-24, 2023; San Francisco, CA.