Abstract

This commentary on a case considers consequences of a so-called “zero-risk” paradigm now common in psychiatric inpatient decision making. Iatrogenic harms of this approach must be balanced against promoting patients’ safety and well-being. This article suggests how to collaboratively assess risk and draw on recovery-oriented goals of care.

Case

LH is a 29-year-old woman hospitalized, so far for 11 days, for a severe episode of depression. Dr Psych estimates she will be hospitalized for another week and is working with risk managers to find a way to allow LH to leave the unit with a staff member to walk in the hospital’s garden, which LH can see from the unit’s windows. LH feels distressed about not having access to fresh air. Dr Psych makes a case to a risk manager for LH’s accompanied access to the garden: it will make her feel better, probably diminish her length of stay, and remove LH’s feeling “imprisoned” as an obstacle to trust and healing in their patient-physician relationship. The risk manager, however, states: “I’m sorry; we just can’t. Two years ago, a patient eloped after being allowed to walk in that garden.” Dr Psych considers how to respond.

Commentary

Health care systems, particularly psychiatric care settings, are currently dominated by a zero-risk paradigm: an approach to ethical decision making that upholds elimination of risk as a shared goal and moral imperative.1,2 The widespread adoption of the zero-risk approach has given rise to dedicated roles for risk managers and a range of interventions and technologies, including, in inpatient psychiatric settings, the use of surveillance, locked doors, and seclusion rooms, all aiming to eliminate risks associated with people experiencing mental health challenges.3,4 Yet growing empirical evidence demonstrates that the zero-risk paradigm and its associated strategies fail to effectively eliminate or even reduce risks associated with self-harm, interpersonal violence, or absconding and instead threaten therapeutic relationships between health care professionals and patients.5,6 Furthermore, zero-risk approaches introduce iatrogenic harms, including physiological side effects from chemical restraints, injuries from physical restraints, and reduced feelings of safety and well-being related to the carceral environment, all of which may additionally lead to worsened mental health symptoms.7,8

This commentary critiques the zero-risk paradigm and grounds the exploration of LH’s case in a safety paradigm, which acknowledges and accepts the potential for some risk throughout the journey from hospitalization to discharge. A safety paradigm further prioritizes the well-being of all individuals in the health care setting—including the patient—with an intrinsic focus on promoting safety rather than eliminating risk. Here, we discuss 3 central strategies of a safety paradigm: conducting meaningful and collaborative safety assessments, employing the recovery model to reconceptualize overarching aims of inpatient psychiatric care, and reenvisioning psychiatric inpatient environments to respond to ethical challenges of lengthy involuntary admissions.

Collaborative Safety Assessments

In its focus on Dr Psych’s engagement with the risk manager, the case of LH presupposes that physicians independently conduct risk assessments, which may then be vetoed by risk managers. We instead propose that utilizing a collaborative, team-based approach to examining risk can elicit a more nuanced picture of the current mental status of a patient. Combining diverse clinical skills of and information from the members of the interdisciplinary team—including nurses, case managers, social workers, therapists, community health care workers, and family members—enriches the context of the assessment because these individuals have strong and potentially long-standing therapeutic relationships with the patient. Risk managers, by contrast, do not have a therapeutic relationship with the patient (due to their role’s precluding meaningful patient engagement over extended periods of time), which therefore limits their ability to conduct a contextualized safety assessment that is responsive to the team’s shared perspectives and tailored to the individual patient’s circumstances. Furthermore, taking a collaborative approach to safety assessments diffuses the decision-making burden by creating a shared sense of responsibility among members of the team.9 While allowing patients access to the outdoors may introduce an element of risk, conducting meaningful and collaborative safety assessments allows for that risk to be thoroughly assessed and potential harm to be reduced. This approach can be especially helpful to the psychiatrist in in LH’s case. By relying on a shared understanding of LH’s mental status and risk, gained through a collaborative team-based approach to risk assessment, the psychiatrist can advocate on behalf of LH to the risk manager with increased confidence and support.

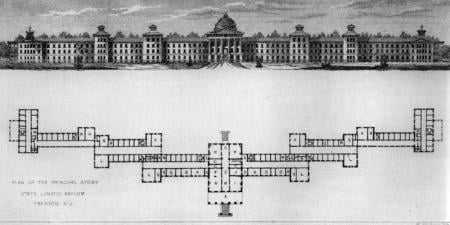

Within current inpatient psychiatric settings, zero-risk approaches have informed environmental design that prioritizes containment and security.

Additionally, safety assessments must be individualized, context-specific, and completed in partnership with the patient.9,10 The dominant zero-risk paradigm in inpatient psychiatric environments does not provide structural support for patients to self-assess their risk or for their self-assessments to be valued. Conversely, including LH as a collaborator in her own care is vital in ensuring her autonomy, accountability, and empowerment over her own mental health and well-being, particularly with respect to activities deemed risky in the psychiatric setting. In the case of LH, the risk manager draws on a prior case of elopement while accessing the garden to inform decision making regarding LH’s opportunity for outdoor access. While prior instances of elopement can increase fear among health care professionals and risk managers, assessment of risk should be based on LH’s current metal status and circumstances, not on her own previous risk or the outcomes of a different patient. Rather, the emphasis should be on acknowledging and supporting LH’s decision-making capacity in tandem with interprofessional assessments. This approach would allow for an individualized, context-specific response to risk management that meets the unique needs of LH.

Recovery-Oriented Practice Model

Recovery has been a goal guiding mental health service delivery since the 1990s. A recovery-oriented practice model has thus been developed for working with clients in both inpatient and community mental health settings.11,12 A central tenet of this model includes understanding recovery as a personal, unique journey for individuals living with mental illnesses. Furthermore, recovery is considered to occur in the context of one’s lifespan, from admission to discharge from inpatient psychiatric settings.13,14 While this model of care has been incorporated widely in community and outpatient mental health settings, its integration into inpatient psychiatric settings remains limited.15,16

Reconceptualizing overarching aims of inpatient psychiatric care through the lens of the recovery-oriented practice model can be beneficial in this case and similar cases in which questions of safety and risk are being evaluated. As discussed, the current widespread adoption of a zero-risk approach in inpatient psychiatric settings aims to eliminate perceived risks associated with people experiencing mental health challenges and requires considerable reduction of symptoms—particularly symptoms considered “behavioral” or associated with potential harms—as a prerequisite for permitting “risky” activities, such as accessing the outdoors.6 In addition to introducing iatrogenic harms, this approach precludes recognition of mental illness as a chronic condition and detracts from a primary focus on improvement of overall well-being of patients. Therefore, we contend that a safety paradigm grounded in the recovery-oriented practice model shifts goals of care from elimination of risks to a reduction in symptoms with a focus on recovery, as defined by the patient. Recovery-oriented goals both shape the aims of an inpatient admission and extend to the person’s life outside the hospital in order to enhance the person’s safety and well-being despite ongoing symptoms.

In the case of LH, Dr Psych’s application of a recovery-oriented lens would affirm her autonomy and build her capacity for vigilance for her own safety and well-being; such an approach has been shown to reduce patients’ feeling of being “imprisoned.”13,14 Promoting LH’s personal efficacy and responsibility might involve Dr Psych supporting activities—such as access to the garden—that include some element of risk but enhance her well-being and give her an opportunity to work toward maintaining her own safety during her inpatient stay. While supporting LH’s access to the garden does have potential for risk, Dr Psych’s taking a recovery-oriented approach to practice within a broader safety paradigm would reorient the goal of a psychiatric inpatient stay from risk elimination to collaboratively supporting the patient’s skills and capacity for maintaining safety and well-being during and following hospitalization. Such arguments could further support Dr Psych in advocating with the risk manager for the necessity of introducing incremental risks, grounded in a recovery-oriented practice model, as capacity-building exercises for the patient en route to eventual discharge.

Reenvisioning Psychiatric Inpatient Environments

Although collaborative safety assessments and a recovery model orientation are approaches that can be immediately implemented to guide ethical decision making related to outdoor access and other activities deemed risky within psychiatric care settings, we further argue that environmental and structural changes are needed for a fundamental shift from a zero-risk to a safety paradigm. Within current inpatient psychiatric settings, zero-risk approaches have informed environmental design that prioritizes containment and security through door locking, secure windows, seclusion rooms, and surveillance technologies.17,18 Although intended to reduce risk and protect patients, the inpatient environment is experienced by both patients and health care professionals as stark, cold, carceral, and not conducive to well-being or recovery.19,20 Psychiatric care settings often do not have secure outdoor spaces, and many patients experience severely restricted access to the outdoors during hospitalizations, enhancing their perceptions of imprisonment and resulting in worsening mental health and well-being.21 Furthermore, racialized groups (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) experience disproportionate negative impacts of the inpatient environment due to systemic racism, stigmatization, and resultant mistrust of health care services.22,23,24 With the maximum average length of psychiatric inpatient hospitalization being 25 days in the United States and the average being 20 days in Canada,25,26 we contend that it is an ethical imperative to ensure patient access to the outdoors that is not contingent on the perceived risks of an individual independently leaving the secure environment of the care setting for a period of time. While current psychiatric settings may not include outdoor space, establishing health system and government policies and standards can ensure that the right to outdoor access is upheld in future building construction.

Co-design of health care systems and processes is an approach that is gaining popularity for its emphasis on including clinician and patient perspectives in the development of innovative and effective solutions to health care problems, and it can be utilized to inform redesign of psychiatric inpatient environments to include secure spaces that also enhance well-being.27,28 Involving patients in the design of inpatient psychiatric environments can further support a reorienting of care provision away from the elimination of risk (through refusal of the “privilege” of outdoor access) toward a system wherein patient safety and well-being are equally prioritized aims of an inpatient stay. It has long been established that outdoor access is a foundational contributor to and prerequisite for well-being,29 and inpatient psychiatric environments must be designed with consideration of not only the implications of permitting outdoor access but also the consequences of restricting it.

Conclusion

In sum, we contend that identifying an acceptable level of risk is a complex decision that must be centered on the individual’s self-assessment and collaborative decision making among members of the interdisciplinary team rather than be reliant on external approval from risk managers. In this case, we propose that Dr Psych engage in a collaborative, team-based approach in partnership with LH and conduct an individualized, context-specific safety assessment that informs the team’s decision making regarding LH’s outdoor access. We further suggest that this decision-making process be grounded in a recovery-oriented practice model that enables a focus on the patient’s capacity building and incremental introduction of risks. Such an approach constitutes a shift from a zero-risk paradigm to a safety paradigm that aims to enhance access to the outdoors and other contributors to well-being, acknowledging a degree of risk along the path toward mental health and recovery.

References

-

Rozel JS. Identifying and understanding legal aspects of emergency psychiatry unique to different jurisdictions. In: Fitz-Gerald MJ, Takeshita J, eds. Models of Emergency Psychiatric Services That Work. Integrating Psychiatry and Primary Care. Springer International Publishing; 2020:165-175.

- St-Pierre I, Holmes D. Managing nurses through disciplinary power: a Foucauldian analysis of workplace violence. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(3):352-359.

- Hearn D. Tracking patients on leave from a secure setting. Ment Health Pract. 2013;16(6):17-21.

- Wortzel HS, Borges LM, McGarity S, et al. Therapeutic risk management for violence: augmenting clinical risk assessment with structured instruments. J Psychiatr Pract. 2020;26(5):405-410.

- Nijman H, Bowers L, Haglund K, Muir-Cochrane E, Simpson A, Van Der Merwe M. Door locking and exit security measures on acute psychiatric admission wards. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(7):614-621.

-

Slemon A, Jenkins E, Bungay V. Safety in psychiatric inpatient care: the impact of risk management culture on mental health nursing practice. Nurs Inq. 2017;24(4):e12199.

-

Franke I, Büsselmann M, Streb J, Dudeck M. Perceived institutional restraint is associated with psychological distress in forensic psychiatric inpatients. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:410.

-

Kersting XAK, Hirsch S, Steinert T. Physical harm and death in the context of coercive measures in psychiatric patients: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:400.

- Davidson L, Tondora J, Pavlo AJ, Stanhope V. Shared decision making within the context of recovery-oriented care. Ment Health Rev (Brighton). 2017;22(3):179-190.

- Hawton K, Lascelles K, Pitman A, Gilbert S, Silverman M. Assessment of suicide risk in mental health practice: shifting from prediction to therapeutic assessment, formulation, and risk management. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(11):922-928.

- Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1993;16(4):11-23.

- Anthony WA. A recovery-oriented service system: setting some system level standards. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2000;24(2):159-168.

-

Chodos H, de’Auteuil S, Martin S, Raymond G, Bartrom M, Lyons D. Guidelines for Recovery-Oriented Practice. Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2015. Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/MHCC_RecoveryGuidelines_ENG_0.pdf

-

Sheedy CK, Whitter M; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Guiding principles and elements of recovery-oriented systems of care: what do we know from the research? US Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. HHS publication (SMA) 09-4439. Accessed January 24, 2023. https://www.naadac.org/assets/2416/sheedyckwhitterm2009_guiding_principles_and_elements.pdf

- Chisholm J, Petrakis M. Clinician perspectives and sense of efficacy about the implementation of recovery-oriented practice in mental health. Br J Soc Work. 2022;52(3):1380-1397.

- Waldemar AK, Arnfred SM, Petersen L, Korsbek L. Recovery-oriented practice in mental health inpatient settings: a literature review. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(6):596-602.

- Berkhout SG, MacGillivray L, Sheehan KA. Carceral politics, inpatient psychiatry, and the pandemic: risk, madness, and containment in COVID-19. Int J Crit Divers Stud. 2021;4(1):74-91.

-

Wilson K, Foye U, Thomas E, et al. Exploring the use of body-worn cameras in acute mental health wards: a qualitative interview study with mental health patients and staff. Int J Nurs Stud. 2023;140:104456.

- Shattell MM, Andes M, Thomas SP. How patients and nurses experience the acute care psychiatric environment. Nurs Inq. 2008;15(3):242-250.

- Slemon A, Bungay V, Jenkins E, Brown H. Power and resistance: nursing students’ experiences in mental health practicums. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2018;41(4):359-376.

- Donald F, Duff C, Lee S, Kroschel J, Kulkarni J. Consumer perspectives on the therapeutic value of a psychiatric environment. J Ment Health. 2015;24(2):63-67.

- Bradley P, Lowell A, Daiyi C, Macklin K, Nagel T, Dunn S. It’s a little bit like prison, but not that much: Aboriginal women’s experiences of an acute mental health inpatient unit. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(4):917-930.

- Smith CM, Daley LA, Lea C, et al. Experiences of Black adults evaluated in a locked psychiatric emergency unit: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv. 2023;74(10):1063-1071.

- Snowden LR, Hastings JF, Alvidrez J. Overrepresentation of black Americans in psychiatric inpatient care. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(6):779-785.

-

Total days stayed for mental health and substance use disorder hospitalizations. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Updated May 2023. Accessed November 29, 2023. https://www.cihi.ca/en/indicators/total-days-stayed-for-mental-health-and-substance-use-disorder-hospitalizations

- Tulloch AD, Fearon P, David AS. Length of stay of general psychiatric inpatients in the United States: systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(3):155-168.

- Tindall RM, Ferris M, Townsend M, Boschert G, Moylan S. A first-hand experience of co-design in mental health service design: opportunities, challenges, and lessons. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(6):1693-1702.

- Zhong R, Wasser T. The cost of safety: balancing risk and liberty in psychiatric units. Bioethics. 2021;35(2):173-177.

-

Harper NJ, Dobud WW, eds. Outdoor Therapies: An Introduction to Practices, Possibilities, and Critical Perspectives. Routledge; 2020.