Abstract

This exploration of the author’s training and experience as a tactical physician underscores the benefits of physicians’ work with law enforcement personnel in field-based operations that are ethically complex. The article points in particular to physicians’ roles in assessing potential risks and benefits—especially of use of force—to promote community safety.

An Accidental Tactical Physician

I had no plans to become a tactical physician, yet, here I am, with body armor, gas mask, weapons, and badge. I have now deployed with my team for more than 50 operations, including service of high-risk warrants, protection of well-known public figures, mass gatherings, and riots. What I have learned and experienced underscores the benefits of physicians’ roles in the field, especially in helping officer colleagues balance potential harms of use of force against securing community safety.

Unlike many physicians who practice tactical medicine, I had no prior emergency medical service, law enforcement, or military experience. Instead, I started by looking for a police officer to collaborate on a firearm injury prevention project. The police department had resources that we, hospital emergency medicine physicians, needed for our project, and we hoped an enthusiastic officer would help. Our project moved forward, and in return I began working with officers from a Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) team. I quickly realized I needed to improve my own firearm skills and tactical knowledge. I understood little about law enforcement and tactical team functioning and needed my team members to teach me. Over the next year, I trained regularly with the SWAT team—my team. I had to participate fully in the training to learn my role as a tactical physician so as to gain my team’s trust. My trauma and emergency department experience did not apply directly in the field, particularly when I was faced with ongoing potential threats. I learned the established protocols of tactical emergency casualty care (TECC),1 which are designed for this setting. I earned the nicknamed “Doc,” which, in the tactical world, expresses not only a professional qualification but also trust and respect. By my fourth mission, I could don my body armor unassisted, and I had streamlined my medical pack to fit the cramped and now comfortably familiar space of our armored truck.

In this article, I discuss physicians’ work with law enforcement personnel in field-based operations, with special attention to the role of physicians in assessing potential risks and benefits of tactical teams intervening to promote community safety.

Trigger Discipline

One role of tactical physicians was impressed upon me by a memorable mission to arrest a suspect with a particularly long and violent criminal career. At the mission briefing we learned that he was heavily armed and had posted threats to police and others on social media. I watched my team enter his home, emerging a short time later with the suspect in our custody. One of my officers walked past me and said, “Doc, with you out here, it’s easier to keep my finger off the trigger.”

Firearm safety rules always include some variation of “ALWAYS keep your finger off the trigger until ready to shoot.”2 Known as trigger discipline, this rule is key in civilian, military, and law enforcement firearm training. We know from countless “accidental,” “unintentional,” or “negligent” shootings that a finger on a trigger is almost always the proximal cause of harm. We also know that even well-trained, experienced firearm operators can neglect trigger discipline when stressed or threatened. My officer’s remark made me more fully appreciate how my role in mitigating risk of harm to bystanders, suspects, officers, and communities extends far beyond providing care.

Warm and Hot Zone Demands

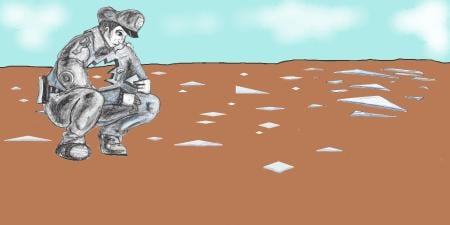

In addition to serving arrest and search warrants or responding to hostage and barricade situations, tactical teams also assist security details for high-profile events (eg, National Football League Super Bowl games). When assigned as a quick response unit for an event, our role is primarily to respond to a potential mass casualty incident (MCI), such as a terrorist attack or the presence of an active shooter, and to prevent further deaths or injuries. In every mission, we divide the scene into zones—the hot zone where the threat is, the warm zone where the threat could go, and the cold zone (which is probably safe). When my team is making an arrest or serving a warrant, I remain in a protected location: the cold zone. But when my team responds to a potential MCI, there is no safe place; I need to move with my team into the warm or hot zone.

“Doc, with you out here, it’s easier to keep my finger off the trigger.”

Anyone in the warm or hot zone is vulnerable. Our team moves rapidly to secure these zones and to stop ongoing threats. Conventional emergency medical services will not go into the hot zone where the threat is or the warm zone where an active shooter or new threats could emerge at any time. Concern for securing the safety of the scene from ongoing threats is a common reason why medical response is delayed in MCIs.3 The principles of TECC dictate that only minimal and immediately lifesaving interventions be performed in the warm zone, where emphasis is placed on rapid evacuation to the cold zone. Because these situations are dynamic, zone classification can change rapidly and the TECC priorities shift as a result. Because in the hot zone the priority is stopping the threat, when I am working with my team as part of a quick response unit for an event, it is essential for me to be armed. Review of relevant law and department policies had taught me that I could only be armed in the role of helping to stop threats if I became a sworn officer. I balanced the obligation I felt to serve my team and the public on the front line against the risks inherent in committing to enter warmer zones, and I enrolled in the police academy.

Nonmaleficence and TECC

For many, the idea of an armed physician serving as part of a tactical unit conflicts with the dictum “first, do no harm.” As scholars have noted, this dictum is not actually a part of the Hippocratic Oath and conflicts with how modern medicine is practiced.4 An armed tactical physician dramatically exemplifies the fine balance of risks at the heart of how modern medicine must be practiced. Any health intervention carries at least some risk of iatrogenic harm; such risk can only be avoided entirely by avoiding any intervention. Weighing the risks and benefits of intervening is done in policing as well as medicine. In addition to providing medical care, part of my role as a tactical physician is to augment my team’s capacity for ethical reflection and serve as a sort of medical conscience. To that end, I help the team weigh potential risks and benefits of actions’ effects on bystanders, suspects, officers, and communities, just as I do so often with patients and their loved ones.

Fundamental to TECC is that, within a hot zone or a warm zone, the greatest threat arises not from victims’ injuries or conditions but from the potential for additional deaths and injuries. A point at which risk of injury or death warrants use of force, including deadly force, must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Just as an oncologist might escalate or stop an intervention based on a patient’s responses, so tactical teams must dynamically assess the appropriateness of using any kind of force—including discharging a firearm—based on the situation, as specified in the International Association of Chiefs of Police Code of Ethics.5 As members of tactical teams, physicians working in warm zones have responsibilities, just like other team members, to be trained and prepared to properly use force if needed and to be prepared and skilled in contributing to deliberations about prospective risks and benefits of using force.

Harm’s Way

The number of deaths caused by iatrogenic harm (including errors) in health care6 is staggering compared to the number of deaths caused by law enforcement personnel.7 Beyond the raw numbers, the critical ethical point is that all members of a tactical team subject themselves, their colleagues, and those whom they seek to serve and protect to the consequences—positive and negative—of tactical and ethical decisions they make in the field. Obviously, I’m not saying that physicians should ever intentionally place themselves in positions that necessitate use of force without providing benefit. What I am saying is that being armed and being skilled in wielding a firearm is key to being a good tactical colleague and to contributing to the creation of an environment in which early critical medical assessment and intervention can be done. Although still debatable, the use of force by any individual—even a physician—in self-defense or in defense of others has long-standing legal and even religious support.8,9 Physicians entering warm zones looking to provide care must assume the risk of possibly needing to take life to preserve life.

When I completed police training, I earned a badge and became an officer sworn to serve and protect our community. I bring my experiences to students and colleagues who are in both law enforcement and health care. Although I hope I never have to use my weapon in the field, I appreciate that it enables me to provide care—at dire times and under austere conditions—to patients for whom such care would otherwise be inaccessible.

References

-

Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC): Course Manual. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2020.

-

NRA gun safety rules. National Rifle Association. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://gunsafetyrules.nra.org/

-

Tierney MT. Facilitating the Medical Response Into an Active Shooter Hot Zone. Master’s thesis. Naval Postgraduate School; 2016.

-

Shelton JD. A piece of my mind: the harm of “first, do no harm.” JAMA. 2000;284(21):2687-2688.

-

Law enforcement code of ethics. International Association of Chiefs of Police. Adopted October 1957. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://www.theiacp.org/resources/law-enforcement-code-of-ethics

-

Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

- Peeples L. What the data say about police shootings. Nature. 2019;573(7772):24-26.

- Kopel D, Eisen J, Gallant P. The human right of self-defense. Brigh Young J Public Law. 2007;22(1):43-178.

-

Lowery Jr J. The historical development of self-defense as excuse for homicide. Ky Law J. 1951;39(4):11.