Abstract

Traumatic imagination includes creative processes in which traumatic memories are transformed into narratives of suffering. This article emphasizes the importance of storytelling in victims’ mental health and offers a literary perspective on how some women’s experiences of suffering can be expressed in the telling of traditional stories, which confer some protection from stigma to individual women in Turkish and Afghan societies.

Representing the Unrepresentable

In war, every word uttered matters. Meanings find expression in stories of suffering that align with one’s worldview, perceptions of oneself, and environment. Telling such stories can become effective ways to channel trauma and create landscapes of resistance.1 Storytelling by women in war, conflict, and hostile environments also symbolizes how “writing from outside power, resists dominant discourses that consistently refuse to include their stories.”2 Arva and Roland, in presenting magical realism as a narrative strategy for representing “unspeakable” historical traumas, state: “[E]stablishing a theoretical link between magical realist writing and trauma requires an interdisciplinary conceptual tool,”3 which they call traumatic imagination.

Traumatic imagination … is intended to describe an empathy-driven consciousness that enables authors (and readers as co-authors of texts) to act out and/or work through trauma by the means of magical realist images.…. [I]t may also be conceptualized as a consciousness of survival to which the psyche resorts when confronted with … compulsive repetition of images of violence and loss. Through magical realist writing, the traumatic imagination transfers to narrative memory events that have been precluded from narrativization by trauma.3

We were drawn to this concept when a colleague in Afghanistan was, as Roland and Arva observed, “struggling to re-present the unpresentable”3 after witnessing an act of extreme violence by Taliban authorities toward a young girl wearing clothes they deemed too short. We apply traumatic imagination to this struggle and more broadly here as we describe the importance of storytelling to mental health. We offer a literary perspective on how women’s individual experiences of suffering find expression in traditional stories and critique the idea that stories of trauma, particularly those related to gender violence in conflict settings, silence voices of women who have experienced trauma.

Traumatic Imagination and Traditional Storytelling

In our work in Afghanistan and Turkey, we have seen how and why traditional storytelling, expressing magical realism deeply rooted in oral storytelling and poetry recitation, is a resource for women who have experienced violence. Traumatic imagination can enable some women to give voice to their suffering borne of conflict. Traditional stories, specifically, can serve as protective cover for storytellers at risk of harm or stigma if they are personally identified. Storytelling traditions in Turkey have been shifting and express modern influences that can be helpful in illuminating violence experiences in other conflict settings (eg, familial or international).4

Situated in transitions from nomadic to settled lifestyles, travellers’ oral tales soon became encumbered by everyday rituals, customs, taboos, and talismans. By the 20th century, the lived realities and experiences of everyday people had inspired literary eras of Turkish writing.5 The social realist and existentialist movements, which preceded and followed the “village novel” period, respectively, expressed points of view from minority groups and represented contrasts between modernity and traditionalism or between East and West.

The literature of the latter half of the 19th century was shaped by the emergence of magical realism, which was rooted in the author or teller’s realistic perceptions of their surroundings but was also infused with the mystical and supernatural. Magical realism was a way to assimilate memories, stories, and legacies that had travelled to modern Turkey from afar. But, perhaps most importantly, magical realism also allowed a writer or teller to “evade and unsettle hegemonic views”6 and has, therefore, resonated with women who resist patriarchy by sharing yet-unheard stories.2 Raza and Imran discuss border space as key in magical realism: “Existence thrives on this border space, neither being overtly on one side nor on the other. Such a liminality is all encompassing as it absorbs two contradictions. By being neither here nor there, it is everywhere, in both regions across the border. Thus, the strip of border space is magical and curtails stark realities simultaneously.”7 That is, a story connects the space bordering violence and the power of a woman storyteller, illuminating the hybridity of a voice not yet heard that speaks. A magically realistic story expresses a human perspective “expounded upon as a tool of magic in the realm of the real.”7 A woman speaking of suffering beyond the boundaries of her own voice might be interpreted as narrating within a storytelling tradition of magical realism, which commonly weaves experiences of everyday living with a greater spirituality or sense of being.

In their analysis of Elif Shafak’s The Gaze, Raza and Imran argue that Shafak’s narration “further develops the notion of hybridity by employing attributes of Self and the Other through stylistic and thematic features.”7 Magical realism offers a way to tie together individual stories of suffering and to connect them to healing via traumatic imagination, which enables this narrative transformation. That is, magical realism in traditional storytelling helps an author or teller transform an experience of trauma into a narrative that can offer meaning for both the teller and the hearer or reader of such stories.

Stories’ Health Applications in Conflict and Peace

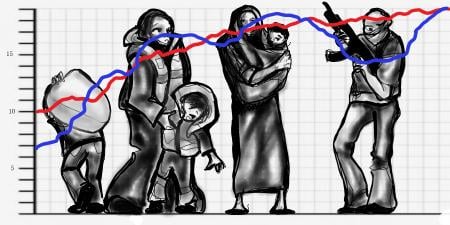

Women suffer harms of physical and psychological violence8 in familial and public spheres of life in times of conflict and peace. Specifically, following the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, violence towards women in the region has escalated, demonstrating an ongoing need for storytelling in women’s collective struggle.9 Connecting one’s own story to traditional stories allows individuals and communities to tap “literacy practices supported by family networks,”10 and participate in community-based mental-health interventions that use storytelling in trauma therapy and recovery.

Importantly, telling stories is not without risk. Women “as storytellers of suffering are the epitome for understanding the lived spaces of war,”11 and risk to their safety stems from their being identified and from the stigma of having suffered violence. Stories in times of conflict remind us that “words and silence are weaponised in war, meaning that a woman’s story is silenced because of what she has the power to reveal, but she is never silent; stories are living breathing vessels of the self and surrounding world.”11 These lessons apply in times of peace, too, as healers can facilitate patients’ storytelling by allowing patients’ stories to be heard as relevant and meaningful, by considering the role of imagination in violence interventions and confidence holding, and by providing spaces for storytelling as sites of healing from both individual and collective trauma.

References

-

Mannell J, Ahmad L, Ahmad A. Narrative storytelling as mental health support for women experiencing gender-based violence in Afghanistan. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:91-98.

-

Abdelrazek AT. Scheherazad’s legacy: Arab-American women writers and the resisting, healing, and connecting power of their storytelling. MIT Electron J Middle East Stud. 2005;5:140-157.

-

Roland H, Arva E. Writing trauma: magical realism and the traumatic imagination. Interférences lit/Lit interferenties. 2014;14:7-14.

-

Stürmer F. Magical realism and trauma in Yaşar Kemal’s “The Pomegranate on the Knoll.” Interférences lit/Lit interferenties. 2014;14:115-128.

-

Parla J, Ertem Ö. Turkish literature. In: Authoritarianism and Resistance in Turkey: Conversations on Democratic and Social Challenges. Springer; 2019:259-267.

-

Asayesh ME. Patriarchy and Power in Magical Realism. Cambridge Scholar Publishing; 2017.

-

Raza M, Imran U. Magic within the ordinary—a probing of Elif Shafak’s “The Gaze.” J Res Rev Soc Sci Pakistan. 2019;2(2):466-478.

- Mannell J, Grewal G, Ahmad L, Ahmad A. A qualitative study of women’s lived experiences of conflict and domestic violence in Afghanistan. Violence Against Women. 2021;27(11):1862-1878.

-

Mwaba K, Senyurek G, Ulman YI, et al. "My story is like a magic wand": a qualitative study of personal storytelling and activism to stop violence against women in Turkey. Glob Health Action. 2021;14(1):1927331.

-

Oates L. Literacy in an extended family household in Kabul: a case study. Lang Lit. 2009;11(1):3.

-

Ahmad A. The trauma of a woman’s words of war. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(10):e491.