Abstract

Although body-mass index (BMI) is regularly used, it has come under clinical and ethical scrutiny. The AMA Code of Medical Ethics offers guidance on the use of diagnostic tools that could be sources of harm to patients.

Imprecision of Body Mass Index

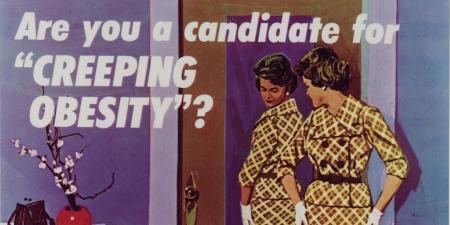

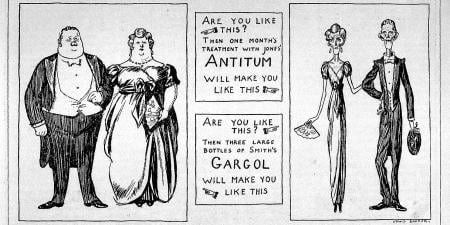

People with overweight or obesity are at increased risk for many serious diseases and health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality.1 However, individuals with overweight or obesity often face bias and discrimination in their daily lives as well as during clinical encounters.2,3 Adults with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 are considered obese,1 but many issues exist with respect to the interpretation and application of BMI, such as the arbitrary cut points used for identifying health risks; the need to adjust those cut points for race/ethnic and sex subgroups; its inability to measure the mass of fat in different body sites; its questionable accuracy in diagnosing obesity, especially in individuals with intermediate BMI; and general patient distrust of its accuracy in assessing the healthiness of their weight.4,5,6,7,8

Physicians’ Ethical Responsibilities

While the American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Medical Ethics does not directly address the use of BMI, 4 opinions are particularly relevant to considering the use of BMI in clinical encounters. Opinion 1.1.6, “Quality,” states that physicians have an obligation “to ensure that the care patients receive is safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable” and that “physicians should actively engage in efforts to improve the quality of health care” by, among other things, monitoring the use of “quality improvement tools.”9 While this opinion does not bar the use of BMI, it does suggest that physicians have a responsibility to ensure that its use is patient centered and equitable and that its effectiveness as a quality improvement tool should be monitored.

Opinion 8.5, “Disparities in Health Care,” dictates that, beyond monitoring quality improvement tools, physicians have a professional obligation to support “the development of quality measures and resources to help reduce disparities.”10 This obligation has important bearings on the use of BMI as a diagnostic tool, as it has become increasingly clear that the current general cut point of 30 to diagnose obesity should be personalized to account for differences in sex and race/ethnicity.8 As Stanford et al note in their research aimed at redefining BMI risk thresholds for metabolic disease: “When obesity is defined by a correlation with the presence of metabolic risk factors, the BMI cutoffs to define obesity would change for specific race/ethnicity and sex subgroups instead of [there being] a single BMI threshold.”8

Opinion 9.3.2, “Physician Responsibilities to Colleagues With Illness, Disability or Impairment,” states: “In carrying out their responsibilities to colleagues, patients, and the public, physicians should strive to … eliminat[e] stigma within the profession regarding illness and disability.”11 Because BMI is often treated as measurably objective despite being a cultural construct, and thus can unintentionally dehumanize patients,4 physicians have a responsibility to minimize and try to eliminate the stigma of obesity that can be exacerbated by the use of BMI as a diagnostic tool. Similarly, Opinion 1.1.3, “Patient Rights,” articulates that the patient-physician relationship should be a collaborative and mutually respectful alliance that upholds the patient’s right to “courtesy, respect, dignity, and timely, responsive attention to his or her needs.”12 Physicians’ awareness of the ways that implicit bias and physician stigma against patients with overweight or obesity can impact patient outcomes is critical to ensuring a respectful and dignified clinical encounter.

Lastly, Opinion 11.2.1, “Professionalism in Health Care Systems,” directly addresses ethical considerations of implementing tools for organizing the delivery of care, such as BMI, and states that physicians should ensure that all such tools “are designed in keeping with sound principles and solid scientific evidence,” are “based on best available evidence and developed in keeping with ethics guidance,” and “are implemented fairly and do not disadvantage identifiable populations of patients or physicians or exacerbate health care disparities.”13 As physicians consider their use of BMI as a diagnostic tool, they should keep in mind how BMI was designed, question whether its use is in keeping with sound scientific evidence, and reflect on whether its implementation is fair and equitable.

References

-

Health effects of overweight and obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed September 24, 2022. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/effects/index.html

- Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):319-326.

- Fruh SM, Nadglowski J, Hall HR, Davis SL, Crook ED, Zlomke K. Obesity stigma and bias. J Nurse Pract. 2016;12(7):425-432.

- Gutin I. In BMI we trust: reframing the body mass index as a measure of health. Soc Theory Health. 2018;16(3):256-271.

- Nuttall FQ. Body mass index: obesity, BMI, and health: a critical review. Nutr Today. 2015;50(3):117-128.

- Humphreys S. The unethical use of BMI in contemporary general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(578):696-697.

- Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, et al. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(6):959-966.

-

Stanford FC, Lee M, Hur C. Race, ethnicity, sex and obesity: is it time to personalize the scale? Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(2):362-369.

-

American Medical Association. Opinion 1.1.6 Quality. Code of Medical Ethics. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/quality

-

American Medical Association. Opinion 8.5 Disparities in health care. Code of Medical Ethics. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/disparities-health-care

-

American Medical Association. Opinion 9.3.2 Physician responsibilities to colleagues with illness, disability or impairment. Code of Medical Ethics. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/physician-responsibilities-colleagues-illness-disability-or-impairment

-

American Medical Association. Opinion 1.1.3 Patient rights. Code of Medical Ethics. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/patient-rights

-

American Medical Association. Opinion 11.2.1 Professionalism in health care systems. Code of Medical Ethics. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/professionalism-health-care-systems