Abstract

Discussions about how to better accommodate fat persons’ needs in health care settings tend to focus on how to reduce stigma and improve equipment (eg, scanners). While important, such efforts must address underlying ideological foundations of stigma and equipment inadequacy, including thin-centrism, a tendency to pathologize fatness, inadequate representation of fat people in health care organizational leadership, and power differentials between clinicians and health care seekers. This article describes how weight-based exclusion and oppression play out in clinical settings and practice as dysfunctional power sharing and suggests strategies for improving clinical relationships.

Fat Suffering and Death

Much of the existing work on better accommodating fat people’s needs within North American health care settings focuses on reducing stigma1 and addressing inadequate medical equipment.2 In some cases, inadequate equipment and surgery-related issues can be a matter of life or death: the computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scanner that was not designed to accommodate the bodies of larger members of the population3; the surgeon who never learned to operate on fat bodies because their medical school refused the donation of fat cadavers4; or the loss of life due to impaired health and well-being from bariatric surgery.5,6 These deaths are, collectively, uncountable; the result, however, is the loss of precious lives and irreversible trauma to families, friends, and communities.

Other outcomes are not as often deadly but may result in significant damage to physical or psychological health when, for example, clinicians’ expressions of weight bias result in “health care seekers”7 of higher weights ceasing all contact with clinicians,8 joint replacements in healthy people being denied on the basis of body mass index (BMI),9,10 or eating disorders being induced or retriggered by the bigoted comments of those entrusted with healing.11 To every survivor of medical weight bias, the suffering, limitation of activities, economic impoverishment through imposed disability, or other negative consequences are lived experiences that come on top of the already serious health impacts of broader social and cultural fatphobia.12

Yet these sequelae of encounters with medical fatphobia cannot be tackled apart from their root causes: the dominance of thin-centric ideology,13 the pathologization of fatness,14 a failure to foster the leadership of fat people,15 and a biomedical health system that continues to elevate the power of physicians over that of health care seekers, fat and otherwise.16 Ultimately, we cannot understand and effectively address the specifics of the induced suffering of fat people within—or excluded from—biomedical contexts without looking to the power inequalities that ground and support them.

Making Change Real

It is vital that iatrogenic harm be recognized and addressed at every level. There are many strategies and tactics that have been outlined for tackling the problems stemming from systemic medical fatphobia.17 Moreover, because, as sociologist Sabrina Strings has demonstrated, medical fatphobia is rooted in historical legacies of white supremacy (particularly, in the form of anti-Black racism), classism, and sexism,18 addressing weight bias must occur in conjunction with a comprehensive commitment to intersectional anti-oppression work that is attentive to the multiple oppressions and painful histories underlying contemporary medico-cultural views of fat people and fat bodies.

Discrimination in health care does not occur apart from the broader contexts of national and regional human rights and antidiscrimination laws. While legislation alone may not always be capable of providing an effective preventative strategy or remedy, the absence of such legal protections against weight bias in most jurisdictions provides implicit endorsement of fat phobic speech and behavior and limits how institutions and individuals can be held accountable for their deleterious impacts.19 Clinicians and scholars in the health sciences have particularly strong and well-regarded voices in the public and political arenas and possess a moral obligation to use their voices to advocate for laws that specifically protect fat health care seekers (and fat colleagues) from discrimination.

At the institutional level—in acute and long-term care settings, ambulatory clinics, medical schools, and regulatory authorities—weight bias must be explicitly included in antidiscrimination policies and efforts be made to ensure that fat people are represented among staff and on boards, committees, and other decision-making bodies. Today, as a matter of course, we take marginalized social groups—most often women, people of color, disabled people, and people with diverse gender and sexual identities—into consideration when hiring or forming steering or advisory committees; by the same token, we must do this for people of differing body size. Without fat people at the table in decision-making roles, meaningful change will not happen, as the experiences of other marginalized communities vividly bear out.20

Twenty-first century health care must have no tolerance for clinical relics of oppression.

At the level of clinical practice, change must span a range of spheres. The inaccessibility of the built environment for fat bodies—from sphygmomanometer cuffs to waiting-room chairs to high-tech diagnostic equipment—must be addressed and corrected, as no amount of change in attitudes will compensate for a health care environment that is made only for thin(ner) bodies. Offering health care by phone or video call has already been revolutionary for many disabled health care seekers and should also be encouraged and supported for fat people.21

Equally important is to have health care spaces free from items that have been and continue to be used to pathologize and humiliate fat people, from weight-measurement scales to skin calipers to exam gowns. Many individuals have traumatic personal experiences with these material objects, as such tools also carry embedded histories of the medical “abnormalization” of fatness and the objectification of bodies. Twenty-first century health care must have no tolerance for clinical relics of oppression, especially given the paucity of useful clinical information to be gleaned from weight/BMI measurement and the profound racism it perpetuates.22 Such items in a clinical setting may telegraph to marginalized health care seekers that their lives and well-being have already been devalued before a word has been uttered, for they concretize harmful biases and deleterious power relations.23

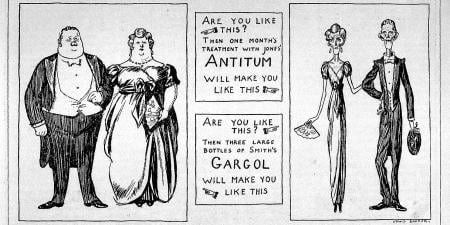

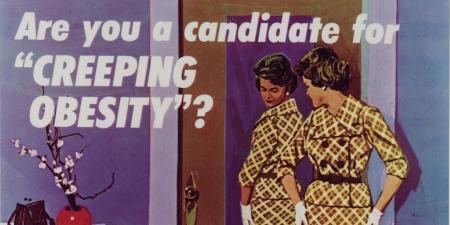

But the ways we think, talk, write about, and depict weight-diverse bodies are no less important. Fat activists have been clear in their demands for the elimination of fat-pathologizing language from both research and clinical practice: “overweight” and “obesity” are terms that “otherize” and do harm to members of the fat community by representing fatness as an abnormal condition.24 With the former term gesturing to the notion that some weights are over a “correct” or “acceptable” weight and the latter originating with the popular belief that fatness is a “disease” and the result of gluttony,25 this language encodes oppression and weight bigotry under a façade of clinical objectivity. As such, it needs to follow other harmful, pathologizing language of the past that degrades human diversity in being discarded, and it needs to be replaced with more neutral language (such as fat or larger bodied).24 In the clinical encounter, weight should only be referenced when necessary and invited by the health care seeker (such as an expressed concern over the clinical significance of an unusually rapid weight gain or loss). Clinical spaces should include positive, weight-inclusive depictions of human beings and bodies (and not stigmatizing posters of fat people to illustrate metabolic syndrome or the like). Clinicians must be alert to the need—arising from generations of abuse by practitioners—to actively and explicitly position their health care environments as weight-neutral, size-diverse, anti-oppressive spaces that guarantee respect for the autonomy and safety of all people, regardless of the body they inhabit.

Power and Domination

Supporting change at all levels requires more than just leadership; it necessitates a genuine worldview change within an organization’s culture. Achieving change in worldview can be considerably harder than achieving change in policies and practices, as fatphobia is not only a deeply entrenched cultural ideology but also a key component of dominant biomedical notions of “health” in research and clinical settings.12,19 Furthermore, both medical and popular conceptions of health go beyond the mere absence of disease, as they are intertwined with cultural values concerning youth, productivity, appearance, and morality, among many other themes.26 Da’Shaun Harrison, a fat Black disabled scholar and activist, has argued that the contemporary Western conception of health exists in its present form as a tool “to abuse, to dominate, and to subjugate” bodies and persons, particularly those that are fat, Black, or both.27 Eliminating fatphobia in research and clinical practice, therefore, requires reenvisioning the very notion of health itself, who gets to define it, and what it means to provide “care” for “health.”

This dynamic of domination is also evident in health care more broadly. The structure of contemporary biomedicine subjugates vulnerable persons (including, but not only, fat persons) to professional medical power, allowing clinicians to violate other human beings’ bodies, including sexually; to permit or deny adults direct access to testing, diagnosis, and therapeutics; and even to physically or medically restrain certain individuals from exercising their basic freedom from treatment and involuntary confinement. All of these unjust relations of power are deeply interrelated and have been critiqued by feminist, disabled, Mad, and fat activists and scholars over the years; yet, by and large, they remain in place.28 A health care system that truly values fat human beings must be one in which liberty and freedom of choice are always protected and centered. Fat people’s health liberation is intertwined with that of members of other marginalized communities. Anything less than an intersectional approach to fat justice in health care is simply a Band-Aid placed over a gaping wound of medical paternalism, oppression, and perpetually reinscribed trauma.29

Fattening Health Care

A comprehensive, ethical approach to fat-positive health care can, therefore, be guided by the following ideas:

- Weight diversity must be acknowledged as a natural feature of humanity and as a manifestation of the genetic variation that has allowed our species to successfully survive into the present. “Excess weight” is a myth. Fat people enrich humanity in a biological sense, through genetic and physiological diversity, not only in a sociocultural one.

- Fat people are to be recognized as a community who continue to face systemic oppression, barriers to equitable power and resources, and a denial of definitional autonomy (that is, the freedom to craft one’s own self-understanding and to have it acknowledged as valid by others).

- Fat people are to be represented in leadership and decision-making positions—not as tokens, but as socially and politically aware agents whose contributions to institutional change are supported, valued, and understood to enhance care for everyone.

- All spaces and equipment within a clinical environment should be size- and weight-accessible; this is true for health care seekers of all ages, including pediatric ones.

- Medical or surgical treatments that intentionally attempt to manipulate body weight should not be offered and should be recognized as manifestations of a biased (and racist) cultural mindset that positions some body sizes as inherently abnormal.

In sum, fat justice in health care cannot exist outside of a comprehensive commitment to reenvisioning health care for all people—and redesigning health care settings as places of dignity, of respect for autonomy, and of healing in its fullest sense.

References

-

Flint SW. Obesity stigma: prevalence and impact in healthcare. Brit J Obes. 2015;(1):14-18.

- Kukielka E. How safety is compromised when hospital equipment is a poor fit for patients who are obese. Patient Saf. 2022;4(2):49-56.

-

Size and weight considerations for imaging and image-guided interventions. UCSF Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://radiology.ucsf.edu/patient-care/patient-safety/size-weight

-

Aleccia J. Donating your body to science? Nobody wants a chubby corpse. NBC News. January 9, 2012. Accessed August 20, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/healthmain/donating-your-body-science-nobody-wants-chubby-corpse-1c6436539

- Castaneda D, Popov VB, Wander P, Thompson CC. Risk of suicide and self-harm is increased after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;29(1):322-333.

- Gribsholt SB, Thomsen RW, Svensson E, Richelsen B. Overall and cause-specific mortality after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a nationwide cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):581-587.

-

Costa DSJ, Mercieca-Bebber R, Tesson S, Seidler Z, Lopez AL. Patient, client, consumer, survivor or other alternatives? A scoping review of preferred terms for labelling individuals who access healthcare across settings. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e025166.

-

Gordon A. Weight stigma kept me out of doctors’ offices for almost a decade. Self. June 26, 2018. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.self.com/story/weight-stigma-kept-me-out-of-doctors-offices

- Giori NJ, Amanatullah DF, Gupta S, Bowe T, Harris AHS. Risk reduction compared with access to care: quantifying the trade-off of enforcing a body mass index eligibility criterion for joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(7):539-545.

-

Chastain R. Jumping through hoops for knee surgery. Dances With Fat blog. July 11, 2017. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://danceswithfat.org/2017/07/11/jumping-through-hoops-for-knee-surgery/

- Westby A, Jones CM, Loth KA. The role of weight stigma in the development of eating disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(1):7-9.

-

Bacon L, Severson A. Fat is not the problem—fat stigma is. Scientific American blog. July 8, 2019. Accessed August 26, 2022 https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/fat-is-not-the-problem-fat-stigma-is/

-

Vigarello G. The Metamorphoses of Fat: A History of Obesity. Delogu CJ, trans. Columbia University Press; 2013.

-

Hillel S. Never Satisfied: A Cultural History of Diets, Fantasies, and Fat. Free Press; 1986.

-

The Fat Doctor. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.fatdoctor.co.uk/

- Gutin A. In BMI we trust: reframing the body mass index as a measure of health. Soc Theory Health. 2018;16(3):256-271.

-

Chastain R. Navigate medical weight stigma by creating an appointment action plan. Weight and Healthcare Newsletter. January 7, 2023. Accessed February 19, 2023. https://weightandhealthcare.substack.com/p/navigate-medical-weight-stigma-by

-

Strings S. Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia. New York University Press; 2019.

-

Eidelson J. Yes, you can still be fired for being fat. Bloomberg. March 15, 2022. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-03-15/weight-discrimination-remains-legal-in-most-of-the-u-s

- Pololi L, Cooper LA, Carr P. Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1363-1369.

-

Vine G. Benefits of online healthcare if one has a disability. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020;4(1):e000851.

-

Strings S, Bacon L. The racist roots of fighting obesity. Scientific American. June 4, 2020. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-racist-roots-of-fighting-obesity2/

-

Mackenzie K. These “don’t weigh me’ cards” are game-changing for doctors appointments. Self. January 28, 2022. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.self.com/story/dont-weigh-me-cards

-

Pausé C. Changing the terminology to “people with obesity” won’t reduce stigma against fat people. The Conversation. October 14, 2019. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://theconversation.com/changing-the-terminology-to-people-with-obesity-wont-reduce-stigma-against-fat-people-124266

-

Gilman SL. Fat: A Cultural History of Obesity. Polity Press; 2008.

-

Crawford R. A cultural account of “health”: control, release, and the social body. In: McKinlay JB, ed. Issues in the Political Economy of Health Care. Tavistock; 1985:60-103.

-

Harrison DL. Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness. North Atlantic Books; 2021.

-

Minkowitz T. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and liberation from psychiatric oppression. In: Burstow B, LeFrancois B, Diamond S, eds. Psychiatry Disrupted: Theorizing Resistance and Crafting the (R)evolution. McGill-Queens University Press; 2014:129-144.

-

Hardy K. Pulling up the tangled roots: biomedical oppression and fat liberation. Polyphony. November 16, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://thepolyphony.org/2021/11/16/pulling-up-the-tangled-roots-biomedical-oppression-and-fat-liberation/