Abstract

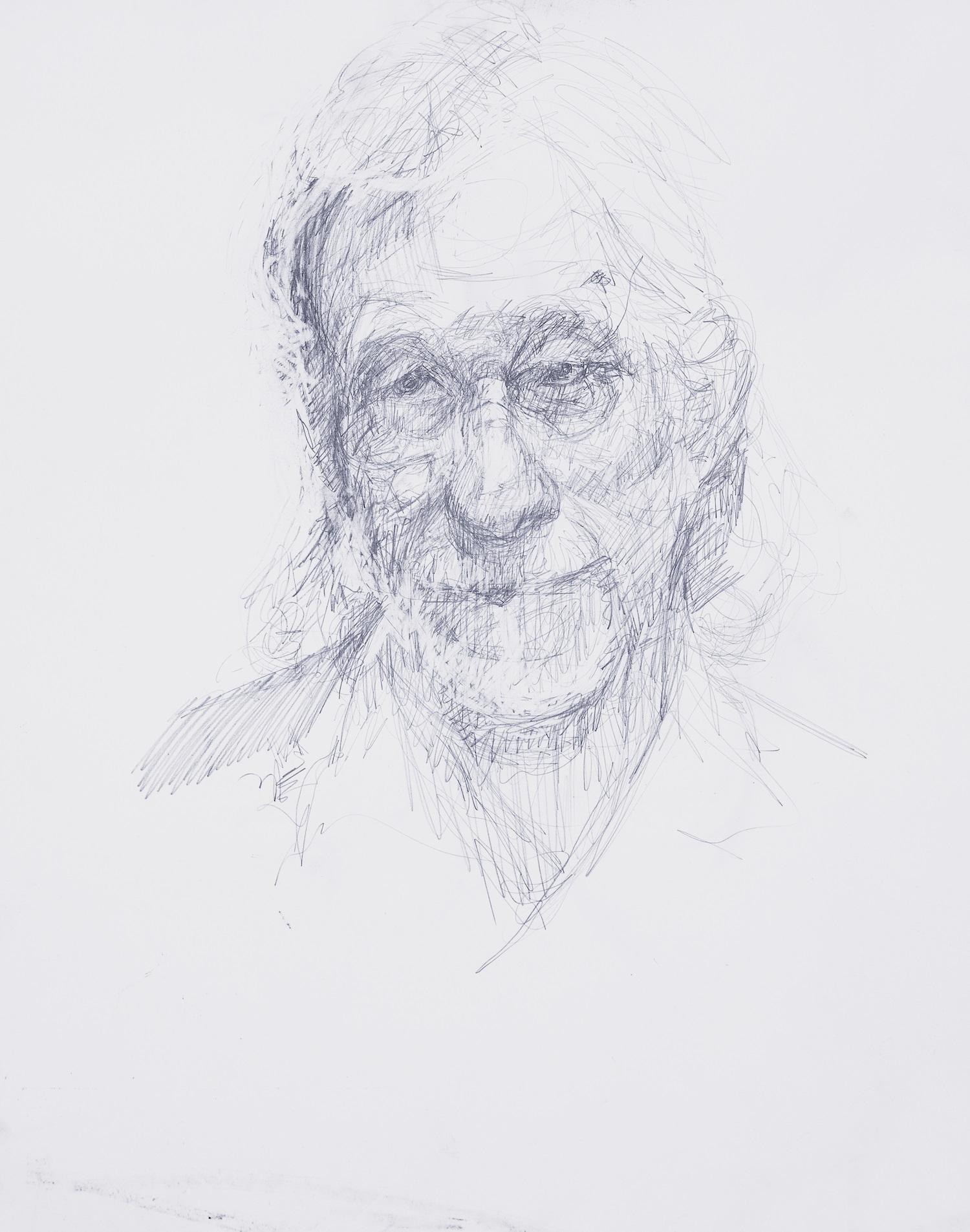

Two portraits of Barry, a housekeeping utility worker at the Veterans Memorial Hospital Memory Clinic in Halifax, Nova Scotia, are part of 80-piece arts-based research collection, led by this article’s author, portrait artist Mark Gilbert. The 2-year study, Giving, Receiving, Observing & Witnessing Care (GROWing Care), explored experiences of patients living with dementia and their caregivers.

In collaboration with geriatrician Kenneth Rockwood, I co-designed the 2-year study, Giving, Receiving, Observing & Witnessing Care (GROWing Care) to explore experiences and to observe, in drawn and painted portraits, a range of interactions among older adults and their partners in care.1,2 In time, we broadened the study’s scope to include consideration of and regard for clinically and ethically relevant roles played by professional health care environmental services workers, including Barry.

Figure 1. Barry, 2018

Courtesy of Mark Gilbert.

Media

Pencil on paper, 18" x 22".

I would see Barry at the end of each day just as he was beginning his 3:30 to 11:30 pm shift, and I was leaving. After Barry agreed to participate in the study and sit for his portrait, he visited me in my studio in the memory clinic. He sat with me there for an hour or so at a time while I drew him. During sittings, Barry described the daily responsibilities included in his “full service” maintenance of memory clinic offices (eg, of chaplains and pharmacists) and care spaces: emptying garbage, dusting vents, mopping and vacuuming floors, and sanitizing furniture equipment, such as pressure cuffs in 7 examination rooms. One of Barry’s major responsibility sets included “ward checks,” which required detailed cleaning of 4 floors of patients’ rooms and common areas, emptying garbage, and removing soiled materials. Barry carried a pager, responding to calls to clean up “spills” in patients’ rooms.

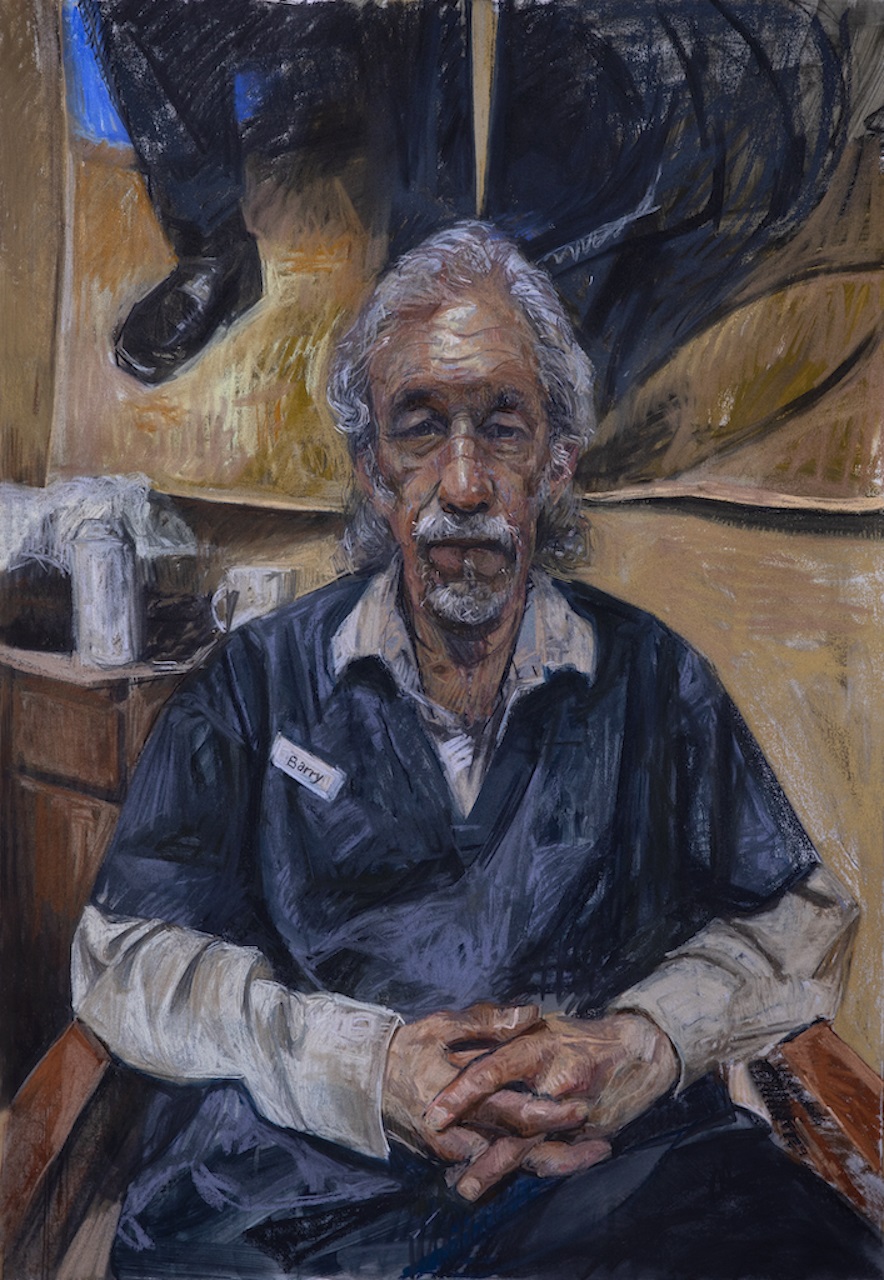

Figure 2. Barry, 2019

Courtesy of Mark Gilbert.

Media

Pastel on paper, 30" x 43".

At the end of the study, I interviewed Barry in the presence of his portraits. Reflecting on the process, Barry stated, “It’s [been] a good experience…. I found it very enjoyable, actually.” Considering the final pastel portrait, in particular, he said, “I was so surprised [when] I saw it and I said, oh my God, you got my little Barry nametag, you’ve even got the scars on my nose.” Barry recognized how his portrait honors and presents his own experience and status as a health care professional and also testifies to his experience of being portrayed. The portrait transforms these aspects of Barry experience into a permanent aesthetic form. Upon learning of his and others’ portraits’ inclusion in an exhibition, he was comfortable with and eager to learn how viewers might engage with the portraits in different ways. “I think it’s great. I think … people have to make their own interpretation. I would love to be a ‘fly on the wall.’”

References

- Hominick K. On seeing and being seen in dementia care. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(6):E550-E556.

- Gilbert MA, Robbins RE, Rockwood K. Exploring the relationship between geriatric patients and their carers through portraiture: Giving, Receiving, Observing & Witnessing Care (GROWing Care). Eur Ger Med. 2020;11(1):185-187.